This article originally ran on Guns.com on February 23, 2011.

Though recent world records may make you think otherwise, the modern day sniper is an American concept, conceived during the War of Independence.

Its initial psychological impact on the British in 1775 was truly damaging and the Americans saw by selectively targeting officers and non-coms rather than foot soldiers, completely compromised the chain of command and created mayhem in their ranks.

Sniper: the nomenclature is English. It was coined to refer to shooters during the British India campaign who could repeatedly hit the elusive snipe with fowling pieces. And though in a Revolutionary War embattled America the term sniper had yet to emerge, the theory that well placed shots could make up for a lack of resources and military infrastructure took wing. Shooters who could consistently hit a 7 inch target at 250 yards using a Pennsylvania Long Rifle (no kidding) earned the right to be called Expert Marksmen.

In the Revolutionary War the introduction of sniper tactics left the English first indignant and then impotent. In response, the Redcoats promptly termed the practice barbaric, citing an anachronistic code of chivalry (the British also regularly starved Patriot prisoners to death. Chivalry indeed).

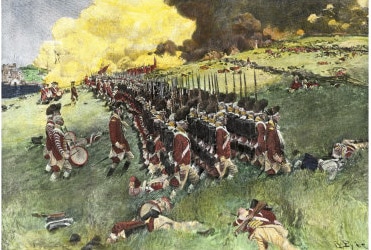

Until the Revolutionary War,

combat was a lethal pageant performed in close ranks in a large field facing the enemy. Lob some cannon balls, stiffly march forward to the fife and drum and have at it, initially with deadly muskets volleys at 60-70 yards, then bayonets and then hand to hand if anybody was still breathing. Throw in some brightly attired Calvary with flashing swords and you have a Pre-Revolutionary battle.

The toll taken by both armies was usually horrific but accepted by the commanding Officers in the rear as the cost of doing business. This thinking would continue past the Revolution in battles under Napoleon and Stalin.

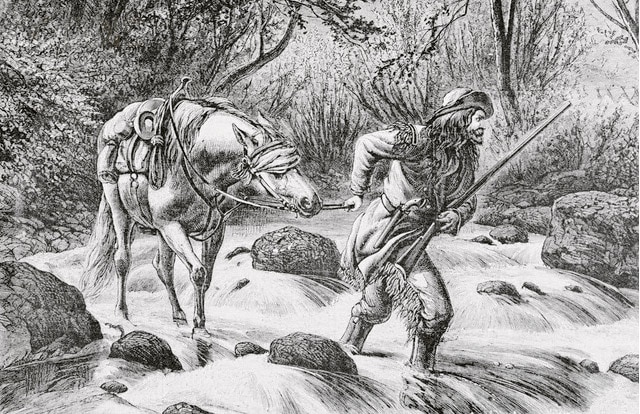

It was the Pennsylvania Long Rifle, coupled with the backwoods skills of the frontier hunters and Indian fighters who fired them, made it feasible for the Patriots to adopt the deadly stalk and hide strategy of the sniper.

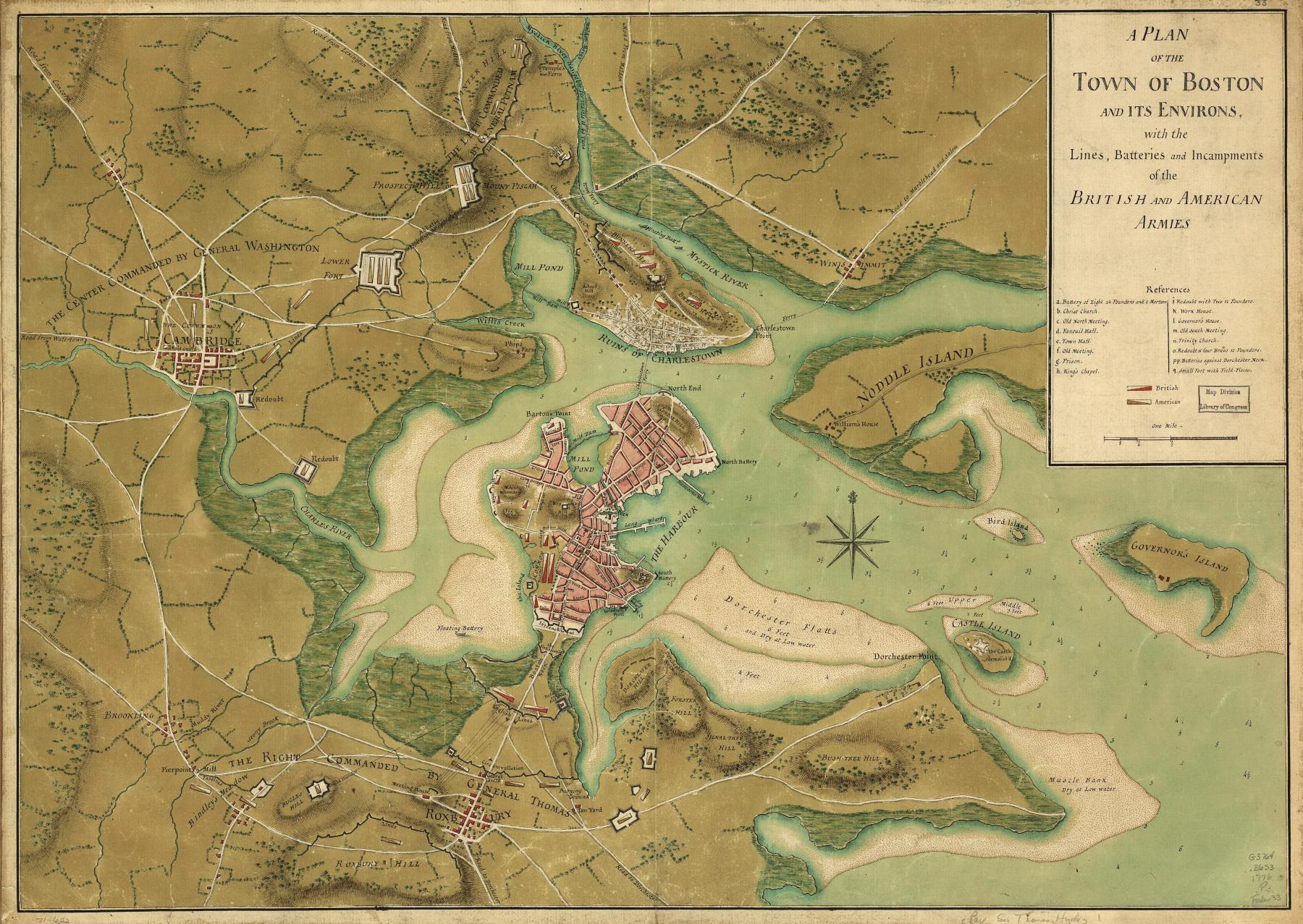

After the indecisive Battles of Lexington and Concord in April of 1775 and just prior to Bunker Hill, the Continental Congress formed the Continental Army. The Provincial Militias from the northern New England Colonies formed by Sam Adams and John Hancock were united under General George Washington, initially to break the stalemate at the Siege of Boston.

In June the Continental Congress sanctioned the first rifle cohort of the new army, forming 10 companies with men drawn from all the Colonies. These units were tasked to stalk the British independently as skirmishers—to disrupt supply lines and track troop movements while all the while targeting officers.

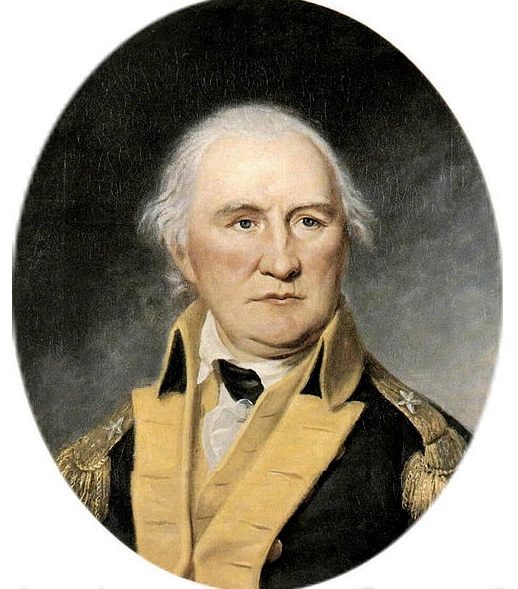

The Virginia House of Burgesses committed two of these companies and promoted New Jersey born Daniel Morgan as Captain and subsequently Colonel to recruit and form the Virginian Company of Marksmen. Morgan was a coarse backwoodsman but supremely suited for the job for more reasons than one. A natural battle tactician, he came fit with skills he had acquired when he served as a musketeer in the Provincial Militias defending western border settlements against the French-backed Indians.

He also had a personal vendetta against the British beyond that of the grander and loftier reasons of succession and representative government (and some would even say these never really concerned him). In 1763, during the siege of Fort Pitt during Pontiac’s Rebellion, Morgan had been sentenced

to 499 lashes by General Braddock—often a death sentence—for striking a superior Officer. It has been said that this incident earned the English his undying enmity and provided Morgan with a notoriously ferocious motivation in battle, one that would ironically be the Royal Army’s undoing.

In July 1775 Morgan assembled 96 volunteers in less than a week in Winchester. He immediately developed military structure and force marched “Morgan’s Riflemen” to Cambridge, Massachusetts arriving ready to fight on August 6.

In Boston, then only armed with muskets, Morgan’s men killed 10 redcoats, 3 of whom were officers scouting the Patriot positions on the first day of the battle. Morgan’s Yanks, and many others, were subsequently all outfitted with Pennsylvania Long Rifles as sniper tactics proved effective against the might of the British Forces.

Conversely, the saying ‘You can always tell a Brit, but not much’ may seem a proven truism as the British obdurately continued to use the Standard Issue ‘Brown Bess’—the limited range smooth bore musket. There had been better-quality European rifles in military use since the 1600s, but most were eschewed with disdain by the British as they were German weapons. The only attempt to counter the efficacy of the Patriot Marksman was the Brit 70th Regiment Afoot, Captained by Frederick Peterson. Peterson was killed by a musket ball to the neck in 1780.

The British Army’s obstinacy in this regard became a huge factor in the decision and development of the new ‘Sharpshooter Corps.’ Immediately it became evident to leaders in the Continental Army that the Brown Bess, accurate to a range of 80 yards, could not compete with the .45 calibre 48 inch barrelled Pennsylvania Long Rifle, especially in the hands of frontier hunters, who had to shoot straight to eat and who were in fact the main clients of the German gun makers in Pennsylvania. The only shortcoming was the length of time it took to load Pennsylvania rifle versus the slightly more expedient Brown Bess. Regardless well placed shots whizzed through branches and levelled battlefields and, for Morgan and his men, it would pretty much stay this way for the balance of the war.

Morgan’s Riflemen were ultimately so proficient in Massachusetts that the Governor, Lieutenant General Thomas Gage resigned his command in favour of Major General William Howe who became Commander-in-Chief. Howe proved equally ineffective, unable to gain the upper hand in the siege, and eventually evacuated Boston and sailed to Halifax in March of 1776.

In the initial Battle of Freeman’s Farm, Morgan’s riflemen began the long-range attack on General John Burgoyne’s troops September 19, 1777 in what is often mistakenly referred to as the Battle of Saratoga. British musket balls fell short, reportedly as harmless as drizzling rain, as Burgoyne attempted to bring his cannons into the fray, but the first officers and then cannon soldiers were picked off by Yankee fire before they could reload. The English were only saved from complete obliteration by a rescue from Baron von Riedesel and his Hessian mercenaries.

Historical accounts also report that some impressive feats of shooting took place during this engagement. Expert Marksman Sergeant Timothy Murphy, one of Colonel Morgan’s very best men, shot and killed both Sir Francis Clerke and General Simon Fraser at 450 yards during the second Battle of Freeman’s farm at Bemis Heights on October 7, 1777.

Murphy’s marksmanship proved a turning point of the war as General ‘Johnny Burgoyen’ was pursued down the Hudson and surrendered 5900 allied British and German Hessians on October 17 at the final exchange in Saratoga.

The war ground on until 1781 but it was apparent to even the supercilious British War Department that their cause in America was lost and the American sniper was born.

The post Which Came First, America or the Sniper? appeared first on Guns.com.