Where Do Our Ducks Come From? The Answer May Shock Many Hunters

America is the chief grower and exporter of wild ducks in North America.

BISMARCK, N.D.—-(AmmoLand.com)- Lost in the euphoria over the 2009 breeding-population survey was the sobering confirmation that prairie Canada is no longer the continent’s leading producer of ducks.

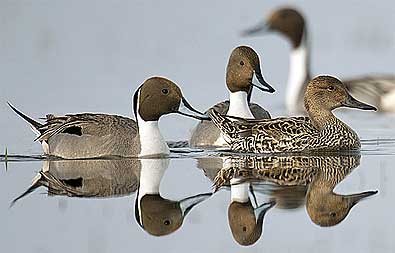

This spring, for the first time ever, more total ducks, more puddle ducks, twice as many pintails and even more redheads settled on the U.S. side of the Prairie Pothole Region (PPR) than the Canadian side.

“Prairie Canada is no longer King of Continental Duck Production,” wrote President Rob Olson in the fall issue of Delta Waterfowl magazine, adding, “From a Canadian duck guy’s perspective, that stings me more than a little.”

While most of the continent’s duck hunters probably don’t care where their ducks come from—so long as they come—Canada’s sagging productivity bodes ill for the long-term future of ducks and duck hunting because it contains two-thirds of the PPR’s nesting habitat.

Wrote Olson: “In spite of the stunning losses of wetlands and shockingly low hatch rates due to unnaturally high levels of predation, Canada still possesses most of the breeding grounds for ducks and most of the remaining wetlands.”

This year’s dramatic shift in breeding-duck numbers seems to confirm what some scientists have long suspected: The U.S. is exporting surplus ducks to Canada, propping up Canada’s breeding population.

“Recent studies suggest there is a large-scale movement of birds from areas of high production, like northeastern North Dakota, to areas where duck production is reduced, like prairie Canada,” said Dr. Frank Rohwer of Louisiana State University in a related magazine article.

Mallards tend to return to areas where they were raised, and when Rohwer, Delta’s scientific director, noticed few juvenile ducks showing up in the U.S. population, he launched a research project to find out why. Young mallards were fitted with radio transmitters in late summer and tracked the following spring. “Most of the marked females returned to the U.S., where they had been raised,” Rohwer says, “but they quickly dispersed great distances.”

Wetland availability determines how many ducks settle in a given area, and this year, says Rohwer, an abundance of wetlands allowed birds that were hatched in the U.S. to nest there rather than being forced to disperse.

“There’s no question we (the U.S.) are a net exporter of ducks,” says Ron Reynolds, who heads up the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Habitat and Population Evaluation Team (HAPET) in Bismarck. “We’re producing surplus ducks that are redistributing to nest in other areas.”

Researchers have long known that productivity was higher on the U.S. side of the PPR than in Canada. Reynolds says the eastern Dakotas make up just 7 percent of the total survey area but produce more than 20 percent of the total ducks. “In the 1990s and early 2000s, the eastern Dakotas were as high as 27 percent,” Reynolds says.

An even more telling number is the percentage of puddle ducks that settle in the eastern Dakotas. This year 40 percent of the mallards, pintails, gadwalls, blue-winged teal and shovelers from the entire survey area, which includes everything from Alaska to the prairies, set up housekeeping in the eastern Dakotas. If the rest of the U.S. PPR is included, 46 percent of puddle ducks settled in the U.S.

Reynolds says the unprecedented buildup of ducks on the U.S. side of the breeding grounds was the result of a late-breaking winter and near-record wetland numbers in the Dakotas. “Ducks had a strong, pent-up demand to settle—the clock was ticking—and they settled in the Dakotas,” he says.

But the U.S. share of nesting puddle ducks has been climbing for two decades. Since 1986, through wet years and dry, the U.S. side of the region has attracted 4.06 ducks for every pond counted in the survey, 46 percent more than Canada’s 2.74 ducks-per-pond.

The year 1986 is significant because that’s the first year the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) began converting cropland to grass cover in the U.S.

CRP, Swampbuster and the federal duck stamp, which secured more than 90 percent of the permanently protected breeding habitat in the U.S., are three important reasons productivity in the U.S. has surpassed Canada.

Canada doesn’t have a CRP-like program, and scientists there confirm a 6.7 percent drop in productivity since the 1970s, most of it attributable to wetland losses ranging from 4.9 to 7.6 percent since 1971.

Reynolds says wetland losses in the U.S., which were once extremely high, slowed after CRP and Swampbuster, which denies crop subsidies to farmers who drain wetlands, were approved.

In addition to the 5 million acres of high-quality nesting cover provided by CRP, the program also protected almost 800,000 acres of wetlands. A Farm Service Agency (FSA) evaluation confirmed some 200,000 acres of “cropped wetlands” are embedded in CRP lands and another 592,000 acres of non-cropped wetlands exist in or adjacent to CRP fields.

Reynolds says the improved function of these CRP wetlands allow them to carry 20 percent more breeding ducks than other wetlands, and the productivity of surrounding landscapes increases as well.

CRP makes up 6 percent of the land area but attracts 30 percent of the nesting ducks.

“That’s pretty amazing,” says Reynolds, who conducted research showing that CRP was responsible for an average of average of around 2 million incremental ducks between 1992 and 2004. “On the wet years, it was probably twice as many,” he says. “And that’s to say nothing of the future generations of ducks that accrue like interest earned on a savings account.”

“The shift in breeding numbers points to a need to protect CRP and the other programs responsible for ducks produced in the U.S., and find innovative ways to restore Canada’s declining duck production,” says Delta Senior Vice President John Devney.

Foremost among those programs, he says, are CRP, Swampbuster, the federal duck stamp and the Clean Water Restoration Act (CWRA) and legislation discouraging the breaking of native prairie.

Just as important, he says, is making Alternative Land Use Services (ALUS) a national program in Canada.

“If we lose some of the critical programs in the U.S. without shoring up production in Canada, duck numbers are going to decrease. That’s why it’s imperative that duck hunters get behind these programs.”

About:

Delta Waterfowl provides knowledge, leaders and science-based solutions that efficiently conserve waterfowl and secure the future for waterfowl hunting.