Chiappa Rhino trigger internals. (Photo: Andy C)

Recently I allowed somebody to pick up my Chiappa Rhino and dry-fire it experimentally. After a few pulls they commented to me, “This has a pretty good trigger!” Immediately I realized the need for this article.

It’s quite likely that many readers here have themselves experienced somebody discussing trigger quality, maybe even using some of the right terms, whose observations don’t reflect reality. As a guide for those who may have less experience in these things, I’d like to introduce some concepts that add up to what makes a gun’s trigger good, poor, or somewhere in-between.

Ergonomics

Ergonomics is the most personal element when it comes to evaluating trigger quality because there exists great variety between people’s hands. Essentially, ergonomics is a question of how two unique geometries–that of your hand and your gun–interact.

Different trigger types on semi-auto handgun and revolver. (Photo: Andy C)

This is precisely why the clichéd advice to pick up a gun and try it for yourself before you buy it is so important. While rifle triggers tend toward uniformity, handgun triggers are diverse. Variables include the distance from the back of the grip to the trigger, the length to reach the trigger itself and the distance of pull. All things considered, the key here is to make sure the trigger ergonomics are comfortable and suited for your intended purpose. I have tiny piano hands, so I never bought a CZ-97 because I found that it is too big for me to manipulate the trigger well.

Additionally, be aware that triggers come in various shapes and at various positions for a reason. Flat, wide triggers are meant for target shooting while curved and narrow ones are meant for faster combat-type shooting. Take my Chiappa Rhino as an example of this: the trigger is a target-type design, but it’s on a handgun designed for practical use (I think?). It’s not comfortable to shoot a whole lot as eventually the edge of the trigger starts to dig into my finger, but it’s wonderful for bullseye shooting because of the wide trigger.

Weight

This is how much effort goes into pulling the trigger. The weight of a trigger varies depending on the mechanism and purpose. While the most common school of thought is ‘less is more’, sacrificing other elements of a trigger pull to reduce the weight (reduced reliability or consistency are common side-effects) are not worth the tradeoff. As long as it doesn’t feel like a trigger is being towed through a bog, some weight can provide you with useful tactile feedback and actually make the gun easier to shoot.

Extremely light triggers are pleasant, but some believe they introduce safety issues with careless handling. If somebody is following gun safety protocol, a very light trigger should never be a problem, but we all know the rules end up broken at the worst times. A small amount of trigger weight can add a fail-safe when the rules are broken.

Consistency

Most triggers in pistols, rifles and shotguns are inherently consistent because the internal mechanism performs the same action with the same surfaces interacting repeatedly. This might change over time as lubricants and carbon infiltrate the mechanism and the surfaces wear, but typically consistency is not a big problem on modern firearm triggers. When it is however, it’s cause for serious alarm. Simply put, if you come across a trigger on a shotgun, rifle or pistol that feels different between squeezes, don’t buy it.

Revolvers are the exception. Because the mechanism on a wheelgun is actually making contact with a different surface for each chamber, there will be variability. Idealy, you want this variation to be as minimal as possible. Wildly different pulls and breaks are the hallmark of poor internal machining and you should pass on such pieces.

Movement

There are a few different elements at play during the tiny movement of a trigger mechanism that need to be each be broken down in order to assess trigger quality. Being able to recognize these traits will make it easier for you to choose a gun with a quality, reliable trigger:

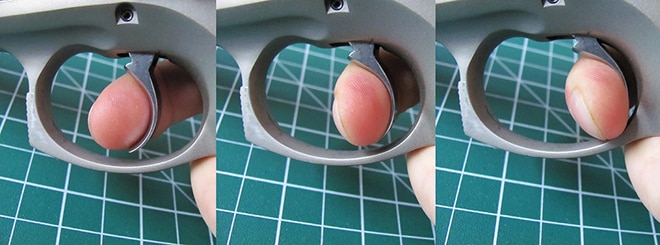

Take-up, creep and break.(Photo: Andy C)

Take-up

Take-up (sometimes called “slack”) is characterized by loose trigger movement when it’s not engaging the seat. If your trigger rattles loosely, that’s take-up; if you can push it back with zero resistance before it starts to engage any kind of mechanism, that’s take-up too.

Here’s an example on a Marlin 1894C. This trigger isn’t being touched; just gravity is moving the blade.

This is undesirable as you want your trigger’s movement to be meaningful. When your finger goes on the trigger and starts pulling, the last thing you need is a feeling of it free-falling backwards, with no idea how hard you’re going to need to push to break the shot. It adds confusion and inconsistency to a small, highly tactile process.

However, of all the negative traits a trigger’s movement can have, I consider take-up the most benign. It’s easy to overcome and in rapid firing its effect is mitigated by riding the trigger to the reset point. Take-up is at its worst on guns that need to be fired with precision a single time quickly like in long guns for hunting. While no take-up is better than some, it’s not a dealbreaker.

Demonstration of take-up. (Photo: Andy C)

Creep

This describes the feeling of increased resistance as the trigger moves backwards towards the break. Creep is present in virtually all triggers. The less noticeable the better. It’s worth noting creep that offers some resistance is also preferable to many shooters, as weak creep with lots of movement produces a “mushy,” uncertain feeling trigger.

Good creep is scarcely noticeable, as the trigger often barely needs to move anyway. Poor creep can be found on a local Mosin-Nagant. While modern firearms of any type rarely have such egregiously bad triggers, noticeable differences exist even in guns from different manufacturers with the same design like 1911s or AR-15s.

During creep, you might come across what is often described as a ‘snag’ or ‘bump’, where it feels like the trigger is about to release a shot, but when more pressure is applied to the trigger, it pushes through this spot and continues on towards the break. Commonly at its worst in double-action handguns, poor creep creates flinches. While it’s difficult to avoid in mass-produced triggers (especially for double-action revolvers), it’s also probably what makes a trigger truly ‘bad’ most of the time. Ruger double-action revolvers often feature creep that leads shooters to ‘stage’ the gun in double-action. This bad habit does the shooter no favors, slowing them down and reducing the consistency of their trigger pull.

Break

This is the point where the firearm discharges. The break point on a trigger pull should fit into the motion seamlessly. You’ve likely been told a good trigger will surprise you with when it goes off; the key to this is it doesn’t tip it’s hand by feeling harder to move (take-up), stalling (creep), or other telltale signs. It also shouldn’t feel strange after breaking, but instead, feel exactly as the prior areas of the trigger pull did; in other words, if not for the feedback of the firing mechanism, you wouldn’t be able to tell where a good break happens.

Over-travel

After a trigger breaks, any rearward travel is considered “over-travel”–unnecessary movement that creates opportunity for shooter error. This is one of the simplest areas of trigger assessment; less is better. Where over-travel exists, be sure to assess the trigger’s movement the same as at point prior to the break as it should feel smooth and consistent.

Reset

Trigger reset is the way it travels back to firing position after the break. This is only important in firearms where multiple trigger pulls are expected in a short time frame like with many semi-automatic handguns.

Trigger reset is like ergonomics in that personal preference weighs heavily. Technically speaking, a shorter reset is best as it allows faster follow-up shots. In reality, most users cannot push a firearm fast enough for that to be a serious consideration. However, of more use is a good tactile reset where there is a sensation that indicates through your trigger finger that the gun is ready to fire again. Some guns notably click their triggers back into place. Also make sure this reset is consistent.

A great example of poor reset were early M&P handguns from S&W. After firing, the trigger was sort of free-floating and there was very little to let you know when you released it forward when it was ready to go again.

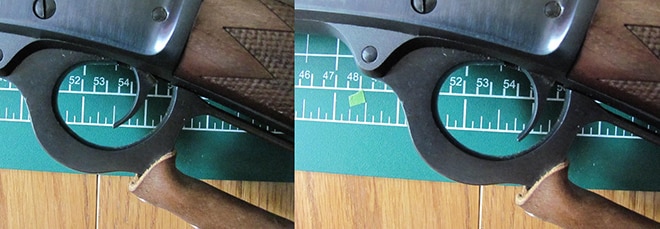

Smoothness

Polished vs unpolished triggers. (Photo: Andy C)

“Grit” is an obvious term that implies a feeling of unevenness in the trigger’s internal workings. “Crunch” is another word applied to very poor triggers. A quality trigger glides back and forth without a sensation of being impeded by anything inside the gun. A rough trigger with poor machining will translate those uneven surfaces into the trigger pull. Gritty triggers are undesirable, but are one of the easier flaws to fix as they usually just requires some polishing and clean up. Other issues (creep, long over-travel) are attributed to the design of the gun and sometimes cannot be fixed without aftermarket products.

Conclusion

For the less-experienced, I hope article helps clear up trigger quality evaluation. Be thoughtful and analytical about firearm triggers. When you’re considering buying a gun, remember every time you use it, you have to deal with the trigger. Don’t turn your nose up at every production firearm over imperfect triggers (or you’ll never own a firearm!), but be honest in your appraisals and test lots of different guns to get a feel for what is good, bad, and ugly. Most importantly, figure out what throws off your own shooting the most and learn to avoid those trigger faults.

The post What’s important when assessing any trigger’s quality? appeared first on Guns.com.