Marketing guns specifically as “women’s” guns needs to be a thing of the past.

The gun industry is chasing its tail in its attempts to design guns for women. Too many women and people who love them have thrown away good money on guns that don’t work out for the female owners.

The problem gun makers are attempting to solve, fitting a gun to the average female, isn’t going to go away with the approach they’re taking. Nor will every woman solve her gun comfort issue by buying product after product.

There is a design solution though, and a slice of American history shows us what it is. Solutions also exist within shooters themselves.

The design problem

Whether it’s the classic “shrink it and pink it” approach, shortening length of pull, making forends thinner, putting high-rise combs on downward-angled stocks, or any other tricks to make guns fit women, it’s already been proven that such approaches don’t work—because there is no average woman.

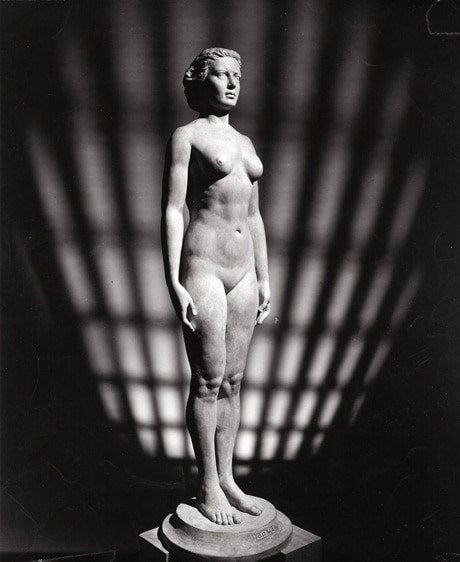

Norma is a representation of the average American female body type in 1943. (Photo: Cleveland Health Museum)

Harvard professor and non-profit executive Todd Rose is known for bringing to light the important discovery that humans are anything but average where body dimensions are concerned. He offers up two examples from the 20th Century—

In 1943, Americans Abram Belski, an artist, and obstetrician/gynecologist Robert Dickson, created a life-size statue called Norma. The alabaster figure is based on the average body measurements from thousands of patients, all ages 21-25, and all white, considering social norms of the era. The sculpture was hailed as the artistic representation of the ideal—and average—modern American woman.

To celebrate the acquisition of Norma as well as the feminine physique, the Cleveland Health Museum sponsored a lookalike contest, to which 3,863 women applied. Less than 40 women’s measurements were deemed to even be somewhat close to Norma’s, and the eventual winner was an inexact match.

Not intending to repeat the Norma experiment, but to contribute to national security, in 1952, USAF researcher Gilbert Daniels attempted to spec out cockpits for the average pilot, in anticipation of a major bid solicitation. Daniels collected data from 4,000 active pilots, using ten dimensions—including some that can apply to gun design, like reach, neck, and shoulder measurements. Not one pilot in the sample proved to be average on every, or even nine of the ten, dimensions.

As for guns, I have a friend who has a so-called ladies model Savage, loves it, and is a successful big game hunter with the rifle. A female colleague tried a similar rifle and found it uncomfortable.

The same range of fit exists in handguns. A female student of mine, who’s shorter and smaller than me at first glance, recently tested my Glock 42. The reach from grip to trigger was much too short, and she struggled to keep her long fingers from going too far into the trigger guard. Another student comfortably packs an H&K P30—a full-size pistol—in her waistband whenever she leaves the house. That same rig would cause me immediate pain.

Life as a shooter and instructor has proven to me that “women’s guns” are a either a marketing ploy or a well-intentioned but useless effort to meet the needs of female shooters for the same reasons already discovered last century: there is no average.

The two-part solution

After the USAF discovered an “average” pilot body could not be accommodated, they went adjustable. (Photo: US National Archives/AP)

Rose’s TED Talk describes how the USAF solved the cockpit design issue. Data in hand, they approached potential bidders and demanded that seats and controls fit the upper and lower ranges of each dimension. Vendors balked, saying it was too expensive. But USAF, in a show of employee solidarity, stood by its request. The result is something most of us enjoy today in our motor vehicles: adjustable seats and other controls. According to Rose, the design change turned out not to even be expensive, once companies got to work on design.

It’s not a huge leap of intellect here to say that gun manufacturers could do more for intelligent, adjustable design. We already have some of these features now—adjustable handgun backstraps are becoming common, collapsible stocks on the AR platform accommodate personalization, and there are others, like the adjustable comb height on many precision rifle stocks.

Notice, none of these features are sex-specific—they allow the shooter choice and customization. That’s something everyone likes, and has to appeal to virtually every gun user, male or female.

The other solution lies within the gun operator. Substantial buying power, backed by beliefs installed by marketing or bad instruction, has led too many new shooters to believe they need the perfectly-fitted firearm in order to shoot well. That’s simply not true. Good instruction and practice can instill safe, effective ways of reaching that magazine release or changing posture to shorten or extend length of pull. New shooters who spend time behind a less-than-perfectly-fitted gun will be more competent in the long run, as they’ve had to think and sometimes work out for themselves how to make things work well.

The post We’ve moved past ‘special’ guns for women appeared first on Guns.com.