Europe -(AmmoLand.com)- The assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914, caught the world by surprise. The global conflict that followed proved how unprepared all sides were when it came to protecting their soldiers on the front lines. Quite simply, most of the guns in use between 1914 and 1918 were far too advanced for the body armor of the day to stand a chance. Nonetheless, many tried to come up with solutions that they hoped would save lives.

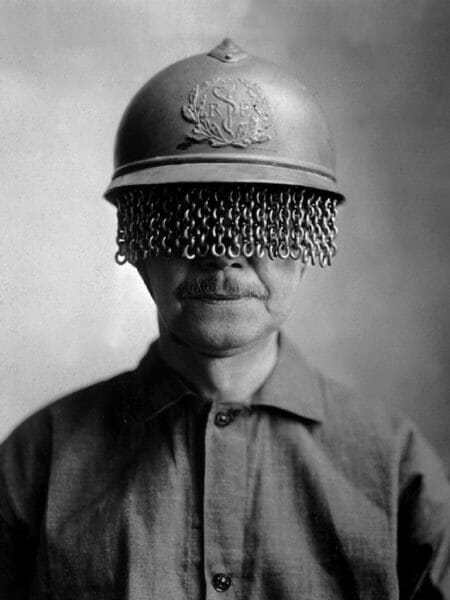

An estimated 1.75 billion artillery shells were launched during the First World War. As a result, shrapnel caused many soldiers’ wounds. One way to protect faces from injury was to wear a mask. The concept was simple, but application varied widely.

Some used chain mail attached to the front of a standard helmet. While no longer effective at protecting from direct blows, chain mail was still a viable way to deflect airborne chunks of metal. In some cases, helmets were equipped with protective visors, much like a knight’s helmet from centuries before, which flipped up when not in use and down when needed for protection.

Another concept took the term “splatter mask” literally, where the soldier simply strapped a crude metal mask that sometimes resembled goggles to their face. This mask had holes and/or slits in it for the soldier to see through, but the openings were very tiny and the field of vision was severely limited. Others combined both the mask and the chain mail in an attempt to provide as much protection as possible.

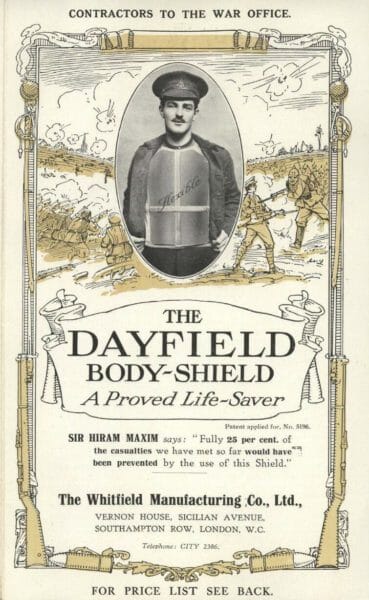

Traditional chest plates, a concept which dates back thousands of years, also found their way onto the fields and into the trenches.

The simplest method used large singular plates of steel; others were made up of smaller plates that resembled scales of a fish or lobster. Regardless of the design, the goal was the same: stop – or at least lessen – the impact from small arms and shrapnel.

The Dayfield Body-Shield from London made a lofty claim: “fully 25 percent of the casualties we have met so far would have been prevented by the use of this shield.” It was high praise coming from Sir Hiram Maxim, whose machine guns were proving exceptionally effective in the field.

Unfortunately, none of them lived up to their claims. Tests performed in France in 1918 resulted in plates perforated by rifle and machine gunfire. To their credit, they could stop some pistol rounds. They were also heavy and cumbersome, making them useful only to sentries or machine gunners – both of whom had jobs that did not require them to move much, if at all.

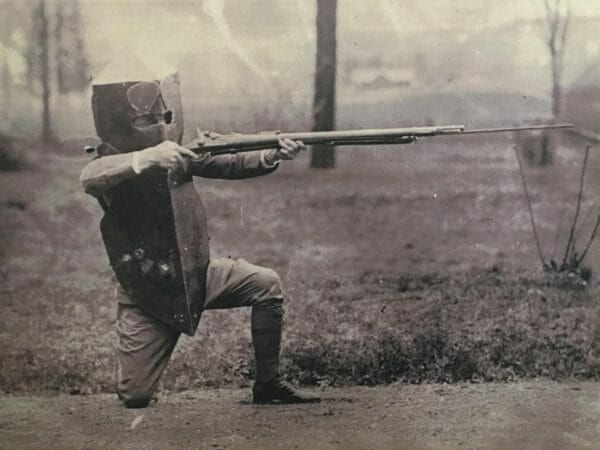

Arguably the most visually distinct armor was designed by Dr. Guy Otis Brewster of New Jersey. The V-shape of his oversized, armored chest piece and helmet was designed to deflect and divert rounds. A slot in the helmet to permit vision could be sealed off by way of two rotating round plates. Brewster’s armor was contoured for improved mobility, but it lacked any protection for the arms or legs. Moreover, the entire suit weighed a whopping 40 pounds.

Confident in its utility, Brewster himself donned the suit while taking fire from a Lewis machine gun in April 1917. Dr. Brewster survived unharmed and claimed that the machine gun’s impacts felt “only about one tenth the shock which I experienced when struck by a sledge-hammer.” Despite the successful trial, Brewster’s armor never saw service.

With much of WWI being fought statically in trenches, both sides yearned for a way to effectively gain ground. To that end, some unusual contraptions were devised that would – in theory – allow soldiers to move through No Man’s Land undercover in an attempt to drive back the enemy.

One option was called a “creeper tank.” These were essentially armored plates on wheels that allowed one user to crawl into from the rear and push it along on the ground towards the enemy. The user was protected on three sides and from the top, but they proved too heavy and cumbersome to be of any use in the muddy expanse between trenches.

Another configuration created by the Russians provided armor plating large enough to completely cover six men in line firing from a kneeling position. Due to the contraption’s size and weight, however, it was too big and heavy to be moved with any degree of ease or speed, even with the intended aid of horses.

In the end, none of the countless ideas for protective gear – no matter how innovative – proved any match for the effectiveness of the weapons used in World War I.

While the designs may have prevented or at least lessened injuries sustained by some men, the numbers were simply too small to have had much impact. It would take a few more decades of innovation for materials like Kevlar to come along and really begin to affect any real change in body armor on the battlefield.

About Logan Metesh

Logan Metesh is a historian with a focus on firearms history and development. He runs High Caliber History LLC and has more than a decade of experience working for the Smithsonian Institution, the National Park Service, and the NRA Museums. His ability to present history and research in an engaging manner has made him a sought after consultant, writer, and museum professional. The ease with which he can recall obscure historical facts and figures makes him very good at Jeopardy!, but exceptionally bad at geometry.