By Tom McHale

USA –-(Ammoland.com) Gun Trigger (noun)

– a small projecting tongue in a firearm that, when pressed by the finger, aka Trigger Pull, actuates the mechanism that discharges the weapon.

Trigger Pull, or more accurately, pressing, a trigger sounds like such a simple thing, doesn’t it? Yank that thing backward and you can’t help but hit whatever you were aiming at, right?

If that were true, then shooting accurately would be really, really easy, because, let’s face it, aiming is not all that hard. The hard part is keeping the gun aligned properly until the bullet is on its way down range.

Like most things in life, it’s not nearly so simple. A good trigger pull can make all the difference in a gun’s accuracy.

Trigger pull does nothing to alter the launch and subsequent flight of a bullet, but it has everything to do with helping the shooter to fire the gun with repeatable precision.

That’s because guns are rarely bolted to the bench. Since they’re handheld tools, any movement of any part of the gun during the firing process can impact the alignment of the bore with the target up until the point where the bullet leaves the barrel. A trigger that requires many pounds of force to release, or one that is rough and jerky, can impart just enough movement to the firing platform to cause a miss.

As a result, a high-quality gun trigger with good trigger pull is a big deal. Precise design, engineering, and construction are worth their weight in gold. But there’s a lot more to a quality trigger pull in trigger design than just smoothness of operation. Yes, a trigger causes the release of either a hammer or striker, enabling it to hit a firing pin, causing detonation of the primer in a cartridge, which then ignites the powder. The (relatively) small amount of energy of a trigger press enables the release of a much larger amount of energy. A good gun trigger often has additional functions.

Trigger Pull is easily measured with a Lyman – Electronic Trigger Pull Gauge

A good trigger pull trigger must…

In many gun designs, a trigger also provides the cocking function. We tend to make that whole single-action vs. double-action trigger pull discussion far too confusing. Think of the difference this way. With a single-action gun, like a Ruger Super Blackhawk or 1911, the gun trigger does just one, or a “single” thing. It releases the already cocked hammer. In a double-action design like a Smith & Wesson Model 66 Combat Magnum, the trigger can also release a pre-cocked hammer, but it can also be used to cock AND release the hammer. That’s two actions, hence the term double-action. Within double-action designs, there are handguns that can only fire in double-action mode (Double Action Only or DAO) and double-action / single-action mode (DA/SA).

It must be designed to be accident proof. A drop, bump, or other type of impact should not cause a gun trigger to release prematurely.

It must also account for a change of mind. If the shooter begins a trigger press, but decides not to fire the shot, for whatever reason, the trigger must be able to do a partial reset and return to it’s starting configuration with no input from the shooter.

We wouldn’t want to have a gun trigger in a condition where the trigger remains 75% pulled.

Trigger pull must operate consistently, with the same feel and weight, over time. It must also be resistant to environmental challenges like dirt, dust or powder residue.

Good triggers might need to properly and reliably interface with other components. For example, some triggers deactivate a firing pin block while others interface with various types of safety disconnectors. For example, a disconnector might prevents firing until the slide or bolt is fully locked.

It must reliably reset every time is a shot is fired. Whether or not the shooter immediately releases pressure on the trigger, it must capture the hammer or striker in anticipation of a subsequent shot.

A really good gun trigger pull might also be adjustable, not just for pressure, but for the amount of travel after the shot is released. Many higher end rifles and handguns have over travel adjustments that allow the user to minimize the amount of trigger pull travel that occurs after the shot is broken.

Even The Simple Gun Trigger Pull Mechanics Are Complex

Even if you rule out all the potential functions that a trigger might need to address for any given gun design, the simple mechanics of releasing a hammer or striker are surprisingly complex.

First of all, trigger pull designers must contend with the force required to release the hammer. For the intended use of any specific gun, how much force should be required to break the shot? For a bench rest shooter, who is unlikely to be walking around with a loaded rifle, that force threshold might be very low, as in a pound or so. For a self-defense pistol, where inadvertent firing could be tragic, then the force required could be five or ten pounds.

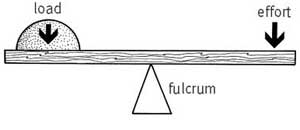

Once the desired force is determined, there are a whole new set of performance considerations. How do you get to that desired level of trigger pull force? As with most things in life, there’s always a tradeoff. If “X” amount of force is required, then it can be overcome with a small amount of trigger movement with more finger pressure, or a longer trigger movement that requires less pressure. It’s the classic fulcrum physics.

You know, with a long enough lever and a proper fulcrum, we could move the earth.

Back in the day, Para Ordnance implemented a Light Double Action trigger design. This one required a longer motion trigger pull, but lighter pressure to break a shot. They made a classic tradeoff of distance traveled versus force required.

Most triggers are hinged, meaning the trigger travels in an arc around a mounting pin. Think of most any rifle trigger, revolver triggers, and AR-type triggers. The arcing movement introduces a whole new set of issues to good trigger pull because the trigger moves along a defined arc, as does the path of a contracting trigger finger.

How do you achieve perfect consistency with one arc motion intersecting a different arc motion in an entirely different plane?

The trigger pull arcs in a vertical plane, while the trigger finger moves in a lateral plane.

Perhaps that’s one reason that John Moses Browning chose a different trigger design for the iconic 1911. On a classic 1911, the trigger itself doesn’t arc around a hinge point at all – the entire trigger moves straight backward as if it was mounted on a rail. The 1911 sear, on the other hand, is a part that rotates around a pin, but your trigger finger doesn’t interface directly with that. Technically, the vertical placement of the trigger finger on the trigger surface doesn’t matter as much as it would on a hinged trigger design.

Common Handgun Trigger Designs

Speaking of hinged and straight slide triggers, there are at least three major categories of pistol triggers:

- 1911-style.

- Hinged double-action.

- Striker.

Even within these broad categories, there are a eleventy-billion variations, but these categories provide a basic idea.

The 1911 Gun Trigger

We’ve already touched on this, but the 1911 design features three major parts to the trigger, not counting variations like firing pin blocks and other disconnector devices.

The gun trigger itself is connected to a sear, which rotates under pressure to release a pre-cocked hammer.

A Double-Action Gun Trigger

With double-action designs, the gun trigger will almost always be hinged. Since the trigger pull has to cock the hammer and release it, more leverage is required and the hinged design is the efficient way to go. In a revolver, this action also drives rotation of the cylinder. All this work is what results in a double-action revolver trigger pull requiring 10 or more pounds to execute a double-action shot. Check out this drawing and animation on science.com to see exactly how the process works.

The Striker-Fired Gun Trigger

A striker-fired design has no hammer. Instead, a striker bar with firing pin rests in a partially “cocked” position. The trigger pull pushes a transfer backwards, which in turn adds more tension to the striker. At a designated point in travel, the striker releases and moves forward, causing the firing pin to impact the cartridge primer. Check out this excellent animation to see how trigger pull works.

The next time someone talks about a “really great trigger pull ” or you see multi-hundred dollar price tag on an aftermarket gun trigger upgrade, consider all that goes into making a trigger work properly. There’s some serious science behind a quality trigger and trigger pull.

About

Tom McHale is the author of the Insanely Practical Guides book series that guides new and experienced shooters alike in a fun, approachable, and practical way. His books are available in print and eBook format on Amazon. You can also find him on Google+, Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest.