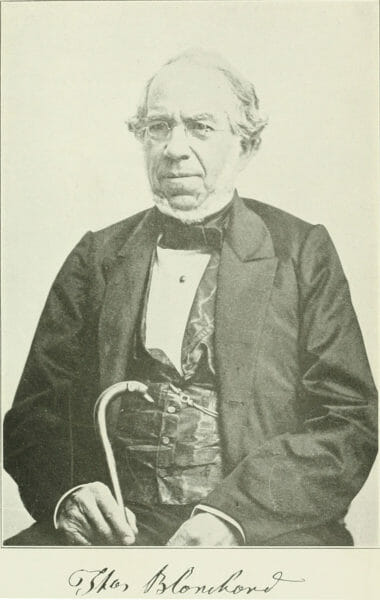

Massachusetts –-(Ammoland.com)- On April 16, 1864, Thomas Blanchard died at the age of 75. He spent his entire life inventing all sorts of things, but some of his best-known creations were for the arms industry.

Blanchard’s life as an inventor focused not on creating new things altogether, but on making existing things faster and easier. His first invention, at age 18, was a machine that produced tacks at a rate of 500 per minute, far superior to anything a human could ever hope to hammer out. He sold the rights for the modern-day equivalent of almost $100,000 – not bad for a first invention!

Blanchard soon found himself working with firearms. His first foray into the field was with government contractor Asa Waters, who was engaged in making flintlock muskets to supplement the numbers made at Springfield Armory. While there, he invented a machine that would uniformly cut the exterior surfaces of musket barrels. In short order, the machine was adopted by the Armory.

After figuring out how to better produce barrels mechanically, Blanchard turned his attention to gunstocks. (There’s a legend that he went this route because he heard a stock shaper say no machine could duplicate the work he did by hand, but it remains exactly that: a legend.)

Whatever the true source of inspiration may be, Blanchard was again successful. In 1822, he finalized what has become known as the “Blanchard Lathe.” The machine used a large iron gunstock as the master over which a guide wheel rolled over, transferring the contours to the cutting wheel on a stock blank.

Within just a few short years, the Blanchard Lathe was in use at both Federal armories in Springfield and Harper’s Ferry. Eventually, the two armories had more than a dozen of these machines all performing different aspects of gunstock production that had previously been done by hand. The only surviving example of an original Blanchard Lathe is on display in the museum at Springfield Armory National Historic Site.

Private industry also took note of the possibilities for Blanchard’s new invention. Soon, Blanchard Lathes were being used in the manufacture of ax handles wagon wheel spokes, shoe lasts, and more.

Blanchard’s standardization of gunstocks was coupled with the emerging idea of parts interchangeability for all aspects of arms makers in the coming decades. James Henry Burton and John Hall, both contemporaries of Blanchard’s at the Federal armories, no doubt looked to his work with gunstocks when they set out to implement complete parts uniformity for standard US-issued firearms.

By the time of his passing, Blanchard held at least two dozen patents in a wide variety of industries. His gunstock lathe, however, is probably the most important and influential of them all. This isn’t just because it has been adopted by so many other industries over the years, but also because his concept is still in use in the arms industry today. There are a number of companies that make stock duplicating machines, and they can be seen in use by modern arms makers and those who look to the past for creating historic replicas.

For example, here’s a clip from a video made at Springfield Armory during WWII with a Blanchard Lathe turning out stocks for the M1 Garand rifle:

And here’s a clip of a worker at Turnbull Restoration using a machine inspired by Blanchard’s Lathe to duplicate a gunstock:

Upon his death, the Springfield Republican referred to Blanchard as “one of the greatest inventors America has ever produced” in the obituary they published. It is, without a doubt, an accurate summation of his life.

About Logan Metesh

Logan Metesh is a historian with a focus on firearms history and development. He runs High Caliber History LLC and has more than a decade of experience working for the Smithsonian Institution, the National Park Service, and the NRA Museums. His ability to present history and research in an engaging manner has made him a sought after consultant, writer, and museum professional. The ease with which he can recall obscure historical facts and figures makes him very good at Jeopardy!, but exceptionally bad at geometry.