Tales to Tell of Grouse & Grouse Hunting

By Michael Mcintosh

Presented by Bernard+Associates

Columbia, SC –-(AmmoLand.com)- Peter Grant turned off the road where the graveled surface ended. This spot had once been occupied by a house trailer, but the owners had long since towed it away, much to the betterment of the countryside.

Now the only view was of woods in every direction. He could have driven to where he was bound, but he’d always preferred to walk the last mile down the narrow dirt road.

Grant opened the rear hatch and shrugged on his vest, checked to see that he had a half-dozen cartridges in each shell pocket, and unbuckled the top of a canvas and leather gunslip. The gun he drew out had been built in London more than a hundred years before, sleek and elegant in its lines, with graceful triggers and hammers filed to a perfect mirror image of one another. It wasn’t the ideal grouse gun, but it was the most beautiful of those he owned, and the one he wanted to carry this day. Draping the gun over his shoulder, Grant set off slowly down the road.

It was an October day such as can only be found in northern Minnesota – cool and still under a brilliant blue sky, a few yellow popple leaves still clinging to their branches, fragrant with the smell of ripening wood fern and the occasional musky thread of stink left by a whitetail buck in rut.

It was all familiar, and Grant found himself treasuring the familiar more and more.

The woods on either side had once been productive grouse coverts, but now the growth was too old to be attractive to the birds. A dog might have found one that had strayed there for reasons known only to itself, but Grant had no dog. His old Brittany had died two years before. He had loved her fiercely through 11 seasons and a long retirement, and Grant no longer owned the energy to train and keep pace with a puppy.

And there was only one bird he hoped to meet that day.

At length, the road curved sharply to the west. That place, too, had once been a good covert, marked by a disused Minneapolis-Moline tractor that had sat there for years, slowly rusting toward oblivion. It was now gone, hauled off to some scrap yard or rescued by a collector who thought it could be restored.

A couple of hundred yards beyond the bend, Grant turned south again at the lane that led to the old farmhouse. Partway there he left the lane and walked a few yards into the woods, found the place he wanted, knelt and brushed leaves from a flat-set granite gravestone. “Laura Peterson – 1882-1898” was all the chiseled legend said.

Laura died nearly 50 years before Grant was born; was even four years older than the gun he carried. She had been 16 when she succumbed to tuberculosis. Grant knew this because he had once talked with some members of the Peterson family, old people then, who told him of their little sister. They described a spritely girl and the sadness they all felt when she died of a disease that was little understood and not treatable in any effective way. Grant had come upon the grave many years before and visited it every time he came to this place. No visit to the old Peterson farm felt complete without a few minutes of silent respect paid at the place where Laura slept.

From the beginning, Grant had felt her as a presence in these woods, lending some elegiac tone to his own presence there. At times, some lines from Thomas Gray echoed in his mind. At other times he simply felt certain Laura was looking kindly upon his roaming where she had roamed and didn’t think him an intruder.

After a while he put his hat back on and continued his slow pace down the lane. This brought him to the house. When he’d first begun hunting here, it was no longer occupied and hadn’t been since. Now it was teetering toward collapse under the weight of time and exposure to the elements and mindless vandalism. Grant had sometimes taken shelter there from rain. Once he’d shared the long, bare, dusty front room with a grouse that apparently had wandered in for the same reason. Grant sat quietly on the floor at one end and watched the bird pace nervously at the other, bobbing its head and keeping a watchful eye. In the end they had struck a truce, though the bird barreled out through the open front door the moment the rain subsided.

Today, he didn’t approach, preferring to remember the old place as it once had been.

The house faced a broad pasture, now much overgrown, that sloped south to the creek. The original path was obscured by the remnants of summer grass, but Grant knew the way. He slanted southwest, toward the bridge and the bird he wanted to find.

The Bridge Bird was something of a legend among the few who hunted this place, always referred to in the capital letters that denoted a given name.

The far end of the old timber span was screened by a narrow band of alder and brush that opened to the uphill woods beyond. It was a tiny piece of cover but ideal for a single grouse, and one was all Grant had ever found there. But one always was there, and Grant had often wondered how many generations had supplied the residents.

The Bridge Bird was thought to be especially cunning, able to elude any opportunity for a clear shot. Clear shots indeed were rare, but the reason had more to do with the environment than with any ubergrouse sensibility. Unless a hunter wanted to wade the creek either upstream or down, the bridge was the only access. The difficulty of negotiating the first few yards of cover and the ruffed grouse’s natural wariness gave the bird a clear advantage. It knew that some potential danger was at hand well before a hunter set foot upon the bridge and had only to scurry to the open side and take wing. Grant had heard more of them there than he’d ever seen.

Whether by sheer chance or the vagaries of fate, he had killed two or three Bridge Birds during the 30 years he’d spent trying to thwart their chances of a safe escape, and despite a grossly lopsided average, each one had been worth all the effort. To Grant, one Bridge Bird was as satisfying, or more, than daily limits taken under less trying conditions.

The Bridge Bird lived somewhere deep in his soul.

Moving as quietly as he could through the grass, Grant gained the near side of the bridge. Like everything around him, it spoke the consequences of age. The timbers and crosspieces were rotting, and the downstream side tipped lower than the other. But it was solid enough to support a crossing, and Grant stepped softly in his rubber-bottomed boots.

The creek ran glossy, deep and dark, fed by spill from an old beaver pond. Grant knew the water was cold enough to support trout, but he had never cast a fly upon it. At any time of year, this was a place for birds.

He stopped at the end of the bridge, dropped two cartridges into his gun, closed the action and cocked both hammers. He had traversed many an alder-brake without enjoying the trip; this one was no different. Holding his gun high in one hand and using the other to fend away the branches while still using them for support, he moved the first few yards with neither mishap nor an unexpected flush. But in this covert the unexpected could be depended upon.

Free of the alder tangle, Grant stopped and waited. The silence alone could sometimes prompt a grouse to flush, like any other ground-dwelling gamebird. Nothing. After a minute or two he pushed into the brush, moving slowly, feeling flutters and pangs in his chest and a familiar pain beginning to gather in his lower back. Too long on your feet, my lad, he thought, and kept moving ahead.

He was nearly out of the brush when the Bridge Bird lost its nerve and hammered up from the edge, angling right to left, into the open. It was a shot Grant seldom missed. He swung up the flight line, passed the bird, lifted his leading hand and fired into the treetops.

It felt like a fitting salute to the place and the time and the many birds that had given him the slip.

Back across the bridge, he hobbled up the slope and found a sunlit tree to lean against as he sat in the grass underneath. He dug out his pipe and tobacco pouch, filled the old briar and set it alight. Exhaling plumes of fragrant smoke like fumes from a censer, he sat for a long time looking at the bridge covert, hoping that as many generations of birds to come would find it, as had the many that came before.

At length he struggled to his feet and set off back up the hill. He would stop to have a look at the old house and pay a respect at Laura’s grave. Then he would make his way down the lane and along the road, knowing beyond all certainty that he would never see this place again.

About:

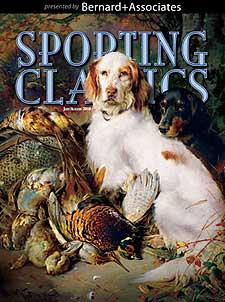

Sporting Classics is the magazine for discovering the best in hunting and fishing worldwide. Every page is carefully crafted, through word and picture, to transport you on an unforgettable journey into the great outdoors.

Travel to the best hunting and fishing destinations. Relive the finest outdoor stories from yesteryear. Discover classic firearms and fishing tackle by the most renowned craftsmen. Gain valuable knowledge from columns written by top experts in their fields: gundogs, shotguns, fly fishing, rifles, art and more.

From great fiction to modern-day adventures, every article is complemented by exciting photography and masterful paintings. This isn’t just another “how to” outdoor magazine. Come. Join us! Visit: www.sportingclassics.net