Opinion

USA – -(AmmoLand.com)- Mass shootings are currently ensconced in the public mind as the definitive example of gun violence in America, having replaced the infamous drive-by that was the obsession of the 80s and early 90s when crack cocaine menaced the country.

And despite the reality that handguns remain by far the weapon used in such incidents, politicians such as Beto O’Rourke insist that the AR-15 and other semiautomatic rifles must be banned for sale and possibly confiscated to deal with the problem.

This particular focus of public attention is, in part the result of confusion over the definition of a mass shooting.

The Gun Violence Archive, a website used frequently by news media, considers the term to mean an incident in which four or more are shot, not including the terrorist, whereas federal law since 2013 has declared a mass shooting to be a case of “3 or more killings in a single incident,” again not including the murderer, modifying the definition from the previous four or more. This lack of commonality in language usage has created the impression that such attacks are happening much more often in recent years, and I suspect that this is the GVA’s intention, but even sticking with the federal definition, we have to acknowledge that there has been an increase in frequency and fatality of mass shootings.

The new attempts at an “assault weapons” ban are a tacit acknowledgment that the 1994 law did not work as advertised. The new approach, as I said above, is to toy with the idea not only of banning future sales, but also to remove legally owned examples of the firearms in question in the hopes that this time, a bad law will suddenly work. Mass shootings did happen during the ten years of the ban, and the acceleration of such events is a recent phenomenon. I have discussed solutions in the past.

Today, I wish to suggest one possible cause with some observations on an implied answer.

Ever since the 9/11 attacks eighteen years ago, we have been told to be afraid, either explicitly or through the implications of our policy choices. We have had to remove our shoes to board an airplane. We were instructed in the use of plastic bags in case of a chemical weapons attack. The phrase, “see something, say something,” was the watchword, though the government didn’t include the warning that no one can be vigilant at all times, as the Boston Marathon bombing illustrates. As a country, we have accepted the government peering over our shoulders and listening to our conversations, despite many of us speaking out against such intrusions. And through all of this, from the president down to the local store owner, the message has been to buy more, an addictive response to calm our anxieties.

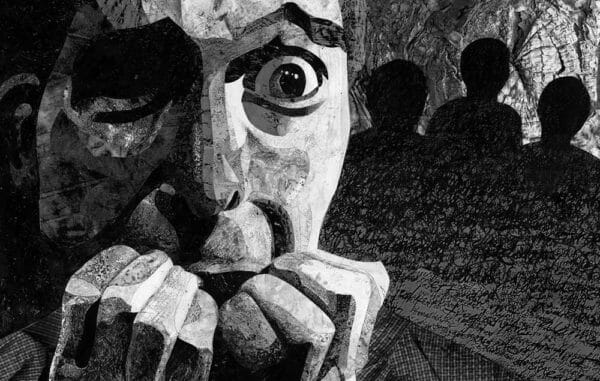

In other words, we are in a state of official paranoia: The Other is coming, and we must fight back. Is it any wonder in this atmosphere that some unhinged persons decide to act, whether that action is taking a rifle to a pizza shop to gain access to the supposed sex-trafficking ring or is a mass shooting for the purpose of keeping a country white?

Our greatest leaders in their moments of greatness have called us to rise above our fears rather than to give in to them. We are a nation defined not by one cultural or ancestral heritage but by the motto “out of many, one.”

If we insist on ignoring or actively rejecting this, mass shootings will be an unsurprising consequence—as will calls to “do something” to make us feel safer. If, instead, we dial down the rhetorical attacks on minorities, if we stop trying to wall ourselves off, we have a stronger argument in favor of rights for all. Doing this would reduce the psychic stress on both gun control advocates and on the individually paranoid in our midst.

About Greg Camp

Greg Camp has taught English composition and literature since 1998 and is the author of six books, including a western, The Willing Spirit, and Each One, Teach One, with Ranjit Singh on gun politics in America. His books can be found on Amazon. He tweets @gregcampnc.