By Katie Lange

USA – -(AmmoLand.com)- Most of the more than 3,500 men who received the Medal of Honor earned it for actions taken during a conflict. Navy Rear Adm. Claud A. Jones, however, is one of the few who received it for his heroics during a mysterious natural disaster.

Jones was born on Oct. 7, 1885, in an area once called Fire Creek, West Virginia. He had a sister named Ida and attended school in Fayetteville and Charleston, both in West Virginia.

After high school, Jones earned an appointment to the Naval Academy, graduating in 1906. He received his commission as an ensign two years later after serving on the battleships Indiana and New Jersey.

From 1909 to 1915, he was assigned to several different ships; he also received post-graduate education at the Naval Academy and at Harvard University, where he earned a Master of Science degree.

By late 1915, Jones was a lieutenant and senior engineering officer on the armored cruiser Tennessee, which was renamed the USS Memphis in May 1916. The Memphis spent that summer at anchor not far off the coast of Santo Domingo City, Santo Domingo, now called the Dominican Republic.

If dangerous weather approached, its crew was prepared to get underway quickly to move to deeper waters. But on Aug. 29, there simply wasn’t enough time. At about 3:45 p.m., the ship’s commanding officer thought the swell was increasing, according to an account from Navy Lt. Cmdr. Thomas Withers Jr., who was on the ship at the time. So, the 31-year-old Jones and his fellow sailors in the engine room began readying the ship’s boilers and engines to get underway.

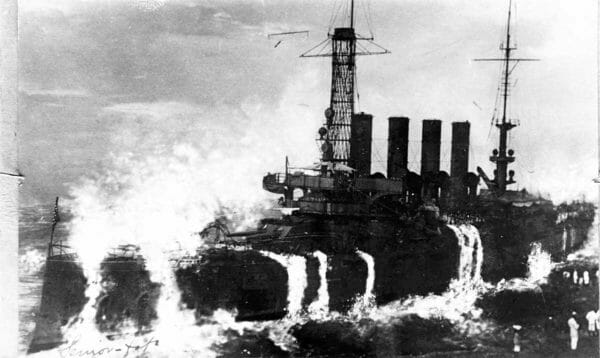

But before the engines had time to get the ship moving further out to sea, enormous waves — unaccompanied by wind — began smashing into the ship without warning.

“Wave followed wave at intervals of perhaps 30-40 seconds,” Withers recounted in a journal. “These waves were so large and their faces became so steep that they simply flowed over the ship.”

The waves, which reportedly reached up to 75 feet high, began to drag the ship toward the beach. Quickly, anything below deck became a death trap.

In the engine room, boilers and steam pipes burst open around Jones, scalding him in steam. Thousands of tons of water came down on him as he remained in the room in near darkness. Jones refused to leave his post because he thought he’d heard the engines turning, even though Withers later said what he’d heard was “the engines breaking up under the pounding they were getting from the bottom of the ship.”

When the boilers exploded, Jones and two other men rushed into the rooms where the boilers were kept, dragging and carrying the men trapped there into rooms where the air was breathable.

Over the next several hours, lifelines to shore were painstakingly established, and they were able to get many of the men to the beachhead safely. However, 43 men lost their lives during the crisis, and many more were seriously injured, including Jones. When he finally made it to the deck of the ship, Jones requested that those who were injured get to shore before him. His bravery and selflessness inspired his men, who refused to go unless he went, too.

The ship didn’t appear to be damaged above the waterline, but below deck was a different story. The hull was crushed by rocks and coral, and the lower decks were flooded, leaving the ship stranded in shallow water. That’s where the wreck remained until 1937, when ship-breaking capabilities became available to salvage it.

An investigation later revealed that a tropical disturbance had passed south of the area the night before, but it didn’t cause any other markers of severe weather except the heavy swells that caused the tragedy.

Jones eventually recovered from his injuries. Soon afterward, he married Margaret Cox. They had a son named Frank and a daughter named Peggy.

Jones remained in the Navy, serving ashore in industrial positions through the end of World War I. He continued to work his way up the ranks, mostly serving in engineering billets. By the early 1930s, he had completed a few Navy Department tours with the Bureau of Engineering, served in London as an assistant naval attaché, and was the senior engineering officer with the battle fleet.

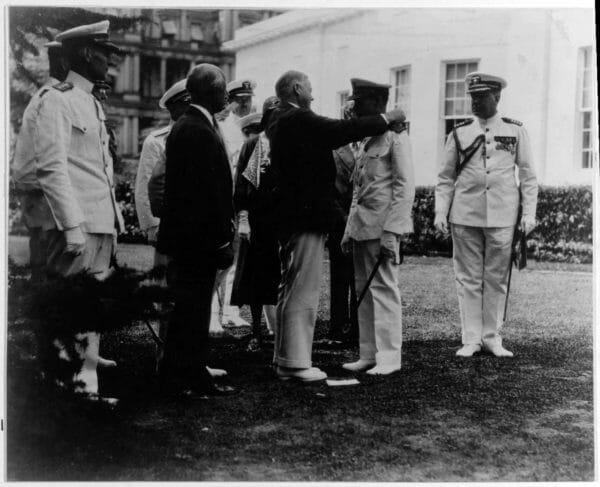

It took years for Jones to be recognized for his heroics during the Memphis wreck. On Aug. 24, 1932, the now-commander received the Medal of Honor from President Herbert Hoover during a White House ceremony. Two of his shipmates also received the high honor: Machinist Charles H. Willey, as well as Chief Machinist’s Mate George William Rud, who died during the incident.

By the early 1940s, Jones was based in Washington, D.C., and had attained the rank of rear admiral when World War II started. Throughout most of the war, he served as an assistant chief for the Navy’s Bureau of Ships and earned the Legion of Merit for his work during that time.

One of Jones’ last roles in the Navy was as director of the Naval Experiment Station in Annapolis, Maryland, a position he held until the end of 1945. He retired in June of 1946.

Unfortunately, on Aug. 8, 1948, Jones died at his home in Charleston, West Virginia, after suffering a stroke. He was 62. Jones was buried with full military honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

His legacy lives on. Jones’ son, Frank, followed in his father’s footsteps by also becoming a rear admiral in the Navy and commanding the Naval Ship Engineering Center in the 1970s. The escort ship USS Claud Jones, which was in service between 1959 and 1974, was named for his father. And, since 1987, the Claud A. Jones Award has been awarded to a fleet or field engineer who’s made significant contributions to improving operational engineering or material readiness.

U.S. Department of Defense

The Department of Defense provides the military forces needed to deter war and ensure our nation’s security. The foundational strength of the Department of Defense is the men and women who volunteer to serve our country and protect our freedoms. Visit www.defense.gov/ to learn more.