U.S.A. –-(Ammoland.com)- While our country has had official arsenals for almost as long as we’ve been around (Springfield and Harpers Ferry were founded when George Washington was president), they didn’t always make all of the guns in-house. Often, the government contracted manufacture of the guns out to smaller, independent gunsmiths.

Such was the case with the Model 1807/8 flintlock martial pistol. For this particular order, seven different contractors produced a total of 1,802 flintlock pistols for the US Government. (Eleven smiths won the contract, but four never produced a single gun.)

Problems with the pistols arose immediately after the guns were delivered to the Schuylkill Arsenal. Upon inspection, almost all of them were rejected. And the problems weren’t confined to just one contractor. They were all guilty of submitting sub-par products.

Even early on, the government had “milspec” standards … and these guns didn’t measure up. One government official quipped, “It would have been better to have thrown the whole amount of purchase in the river, than to have procured with it.” Nonetheless, the government had indeed purchased them to the tune of $5 per pistol. (Our tax dollars have apparently always been spent wisely.)

Martin Fry, based in York, Pennsylvania, was one of the seven ill-fated contractors who delivered guns for the order. In total, he produced 116 pistols, or 58 pairs. All but three, however, were rejected. Today, those three are all that remain of Fry’s short-lived time as a government arms contractor.

Based on his dismal acceptance rate, it would be easy to assume that Martin Fry was just some fly-by-night hack who managed to procure a government contract and was just hoping for the best. Quite the contrary is true, however, because Martin Fry was actually an accomplished gunsmith.

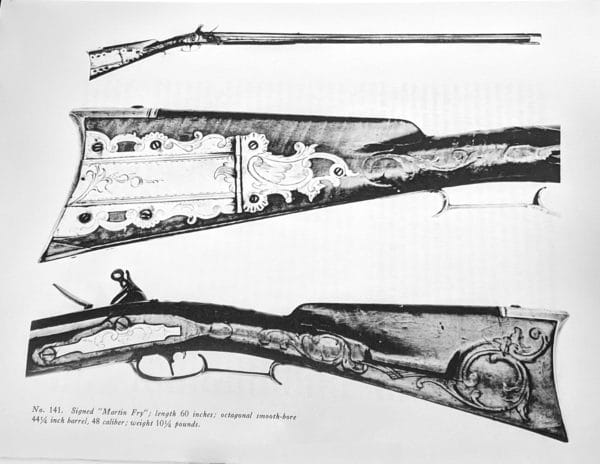

Martin Fry is actually Martin Fry III, and he worked out of his father’s shop which opened in 1762 on Beaver Street between Market and King Streets in York. Martin Fry, Jr. died when Martin Fry III was just 11, so even though he was a second-generation gunsmith, it’s highly unlikely that he truly learned the trade from his father. Nonetheless, he made some beautiful longrifles around the same time as his less-than-stellar government pistols.

So how is it, then, that an accomplished gunsmith like Martin Fry submitted pistols that were so awful that their acceptance rate was a paltry 2.5%? The answer lies not with Fry himself, but with another man by the name of Tench Coxe.

Coxe was appointed as the Purveyor of Public Supplies by President Thomas Jefferson in 1803. The appointment was made at the recommendation of Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin, who was himself a shareholder in a (relatively unsuccessful) Pennsylvania arms factory from 1799 until his appointment in 1801.

Coxe was responsible for procuring arms for both the standing army and the militia. In 1807 and 1808, Congress passed legislation to arm the militia, providing money “for the purpose of providing arms and military equipment for the whole body of the militia of the United States, either by purchase or manufacture.”

As was mentioned at the very beginning, our Federal arsenals couldn’t meet production demands, so much of the work was farmed out to smaller arms makers. Coxe contracted with these makers and even provided monetary advances when necessary.

Coxe was well-intentioned, telling the contractors: “The importance of good arms is manifest…. The lives of our fellow citizens, to whom the use of them is committed, depend upon the excellence of their arms.” Contemporary accounts indicate that Coxe had the technical expertise in the design and manufacture of muskets, rifles, pistols, and swords that you’d expect for someone in his position, but Tench may have bitten off more than he could chew.

Overworked and understaffed, quality control went largely unchecked – unintended though it may have been. In 1810, Coxe fired the inspector in charge of quality control for the arms being acquired, but it would prove to be too little, too late. Letters from 1811 accused Tench Coxe of accepting arms that “were better adapted to kill American soldiers into whose hands they should be put, than an enemy.”

So what, exactly, was wrong with many of these guns? It was observed that some barrels lacked rifling, some were rifled from the muzzle extending just six inches, faulty stocks were filled with glue and sawdust; bore diameter did not match that of the cartridges made for the guns; and some barrels lacked touchholes, making it impossible to fire them.

It was in this environment that Fry submitted his pistols for review by Tench Coxe’s inspector, where 113 of the 116 were rejected. Of the three that were accepted and survive today, two are in their original flintlock configuration and one was converted to percussion at a later time. (As an aside, if anyone knows where the percussion conversion example resides, I’d love to know!)

I’m delighted to say that I’m one of the very few people who have ever held two of the three Fry pistols. The first occasion came when one was placed on loan during the time I worked for the NRA Museums, and the second occasion came when the other flintlock pistol came up for auction in October 2019.

None of the condemned pistols have ever surfaced, so if you ever happen to spot one at an auction or a gun show, make sure to bring it home with you, as it would raise the survival rate of these guns by a whopping 0.9%, bringing it to 3.4%. It’s not much, but every previously-unknown example that surfaces is a big deal in the world of collectors and historians.

So there you have it: a tale as old as time, where private contractors take advantage of the government system and end up costing taxpayers substantial sums of money for subpar goods. As the saying goes: some things never change.

About Logan Metesh

Logan Metesh is a historian with a focus on firearms history and development. He runs High Caliber History LLC and has more than a decade of experience working for the Smithsonian Institution, the National Park Service, and the NRA Museums. His ability to present history and research in an engaging manner has made him a sought after consultant, writer, and museum professional. The ease with which he can recall obscure historical facts and figures makes him very good at Jeopardy!, but exceptionally bad at geometry.