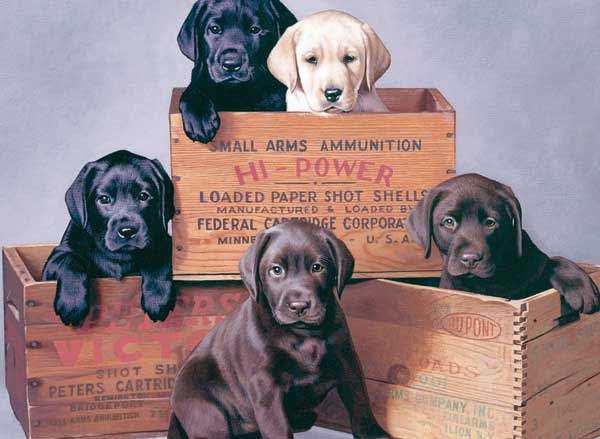

Labrador Retrievers Low Fear, Low Aggression, Compulsive Overeater

Presented by Bernard+Associates

Columbia, SC –-(AmmoLand.com)- A reader asked me the other day why I write so infrequently about Labrador retrievers, pointing out that not only are they the most popular gundog breed in America but the most popular breed, period. For the record, the Lab has been #1 in AKC registrations every year since 1991, and there are no indications it will relinquish that title any time soon.

I also saw a recent Field & Stream survey that, while admittedly not conducted with scientific rigor, yielded the fairly astonishing result that 41 percent of the gundogs owned by its readers are Labs. So if you’re a “typical” American outdoorsman – i.e., a generalist with a broad range of sporting interests – chances are the dog you share those interests with is a sturdily built, ruggedly athletic lad or lass wearing a weatherproof black, yellow or chocolate coat.

In any event, I replied that in fact I write about Labs all the time, just not all the time for this publication. I’m a columnist, you see, for Just Labs, an award-winning magazine spun off from the wildly successful Dale Spartas/Steve Smith book of the same name. With the exception of English setters (and possibly pointers), I’m probably more familiar with Labs –their history, development, strengths, etc. – than I am with any other breed.

That history is fascinating, and thanks to the tireless efforts of the late Richard Wolters, the flamboyant author, showman and bon vivant, we have a remarkably comprehensive picture of it. The record begins in 16th century France, where the monks at the Abbey of St. Hubert – the patron saint of hunting, not coincidentally – bred a black hound celebrated throughout Europe as a tracker and retriever nonpareil. The St. Hubert’s hound was also renowned, according to one source, for “fearing neither water not cold.”

Hmmm . . . What modern hunting breed does that sound like?

Cut to the early 1800s when the descendants of the St. Hubert’s dogs, having first found their way to Devon in the southwest of England, crossed the pond with English fishermen and became established on the Avalon Peninsula of Newfoundland. Known there as the St. John’s dog or the Newfoundland water dog, its duties included diving into the sea to retrieve fish that had come unhooked! Remember, we’re talking the North Atlantic here; the mere thought of those bone-chilling waters makes me want to reach for a Hudson’s Bay blanket and a hot toddy.

The term “Labrador” was first used to describe this breed in 1814. That in itself is instructive regarding the rugged qualities it possessed, Labrador having been famously described by the explorer John Cabot as “the land that God gave Cain.” I’ve been there a couple times myself, and it remains the only place where, within a 24-hour period, I’ve baked in 90-degree sunshine and frozen my ass in a snowstorm.

The point is, these incredibly (if not insanely) demanding conditions cold-forged the Labrador type and endowed the breed with many of its sterling qualities. Its coat, for example. Short, slick and superbly water-repellant, with an outer “shell” of glossy guard hairs and a “lining” of dense underfur – like a waxed-cotton jacket over a wool sweater – it affords a combination of high protection and low maintenance that few if any other breeds can match.

It’s the original “shake dry” garment – although why the owners of this garment invariably shake dry while standing next to their owners remains a question in search of an answer.

The Lab is also endowed with a comparatively generous layer of subcutaneous fat, which serves the dual purpose of further insulating it from the cold and giving it an added measure of buoyancy in the water. This comes at a price, however: a predisposition to obesity and the litany of health problems associated with it. I suspect that there’s a deeply rooted connection between the Lab’s fat layer and its voracious eating habits, habits so frightening in their rapacity that even Dr. Temple Grandin, the well-known animal behaviorist, is at a loss to explain them.

In her insightful book, Animals in Translation, Grandin characterizes the Lab as “a compulsive overeater,” but adds “I don’t think anyone knows why.”

Other adaptations for water-work include webbed feet and the Lab’s distinctive “otter” tail. Designed as a rudder, it’s proved a lifesaver to more than one duck hunter who found himself bobbing in icy water after his skiff capsized and survived only by grabbing his Lab’s stout tail and getting a tow to terra firma.

Still, were it not for the single-minded devotion of a trio of 19th century British aristocrats – Lord Buccleuch and the Earls of Malmsbury and Home, respectively – the Lab might have passed from the scene. Building on the foundation they’d inherited in the St. John’s dog, they selectively bred toward the goal of a producing a keen but biddable retriever of game – a dog that was trainable and obedient, but once slipped, was relentless in its quest to find and recover birds. To say they succeeded hardly does justice to their achievement, and to them goes the lion’s share of the credit for endowing the Lab with the prodigious intelligence and psychological soundness that make the breed so versatile, so adaptable, and such a favorite among so many different “user groups.”

One of the great examples of the Lab’s versatility is the way it took to American pheasant hunting. In Britain the Lab was used primarily as a non-slip retriever, and rarely if ever as a flushing dog. Soon after its importation to the U.S., however (the AKC registered its first Lab in 1917), sportsmen began to discover, to their surprise and delight, that the Lab excelled in this role. It had the nose, it had the desire, it had the athleticism, and it also had the size and strength to bust heavy cover and put skulking roosters to wing. Plus, its retrieving acumen made it just the dog you wanted when that rooster hit the ground – and in particular if it hit the ground running.

A close-working, cover-busting flushing dog that’s hell on cripples: If your goal is tailfeathers sprouting from your game pocket, that’s pretty much the perfect recipe. No one disputes the Lab’s status as the duck dog par excellence, but I think a strong case can be made that the pheasant ultimately played an equally important role in contributing to its popularity here in the Colonies.

The Lab is one of only a handful of breeds characterized as “low fear, low aggression.” Typically a breed that’s low in one is high in the other, and vice-versa. While I suspect that most of the sporting breeds fall into this category (although I have my doubts about a couple), the Lab is clearly the paradigm. Low fear-low aggression translates into a dog that’s wonderful with children, keeps its cool in stressful situations, and is simply a good all-around canine citizen. The Lab’s probably not the best choice for guarding the junkyard, but there has to be something useful that all those pits, Rotts and Dobies can do.

Of course, popularity in dog breeds is always a double-edged sword, as it invariably leads to a spate of indiscriminate breeding that dilutes the gene pool and mass-produces dogs that may look like Labs but don’t have the temperament, trainability and hard-wired behaviors that a Lab’s supposed to have. This is why it’s critically important, regardless of the role you want your Lab to play, to do your homework and deal with a reputable breeder.

Even if that pup you have your heart set on will never get its mouth around a mallard, it should have the desire to hunt and to retrieve. If it doesn’t, it’s just not a Lab.

About:

Sporting Classics is the magazine for discovering the best in hunting and fishing worldwide. Every page is carefully crafted, through word and picture, to transport you on an unforgettable journey into the great outdoors.

Travel to the best hunting and fishing destinations. Relive the finest outdoor stories from yesteryear. Discover classic firearms and fishing tackle by the most renowned craftsmen. Gain valuable knowledge from columns written by top experts in their fields: gundogs, shotguns, fly fishing, rifles, art and more.

From great fiction to modern-day adventures, every article is complemented by exciting photography and masterful paintings. This isn’t just another “how to” outdoor magazine. Come. Join us! Visit: www.sportingclassics.net