USA –-(Ammoland.com)- One wouldn’t think wind could have much effect on a tiny and aerodynamic bullet zipping along at two or three thousand feet per second when long range shooting. But one would be wrong.

Even though most bullets are dense, being made of lead, and moving fast, a small to moderate wind can cause big misses at long distances if you don’t plan accordingly. Let’s consider a few examples using every day calibers and moderate long-distance ranges.

- You’re shooting a .223 Remington 77-grain bullet from an AR-15 at a target 500 yards away. The wind is blowing right to left at just 5 mph. By the time your projectile reaches the target, it will have blown 14.83 inches to the left.

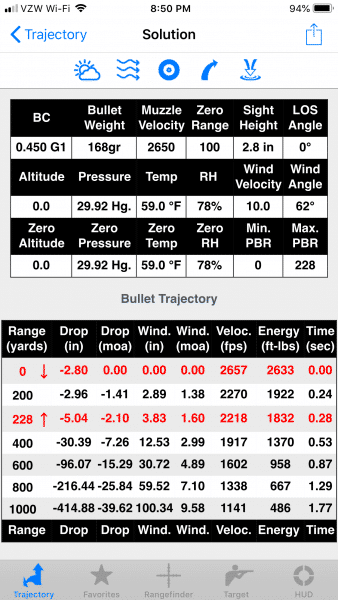

- You’re shooting a 168-grain .308 Winchester at a target 1,000 yards down range. The wind is blowing at 10 mph from the 2 o’clock direction. By the time your bullet reaches the target, it will drift a whopping 100.34 inches sideways. That’s almost 9 feet!

- You’re plinking with a .22 LR and firing 36-grain CCI Mini-Mag bullets at a target 200 yards away. The wind is blowing left to right at 10 mph. Your bullet will blow 22.52 inches to the right. That’s almost as much as it will drop over the 200-yard distance—31.59 inches.

The point is that wind is a big deal when you’re shooting past 100 or 200 yards. Using the .308 Winchester example above, the drift at 100 yards would be just . 71 inches and 2.96 at 200 yards. The same ballistic software computations that can predict bullet drop to surprisingly accurate levels can also predict the effects of wind. The reason that windage is so much more difficult for the shooter is that it’s not steady like gravity. While gravity is constant at the shooting bench, the target down range, and everywhere in between, the wind is more like a putt-putt golf green. Just as the green has changing undulations between your position and the hole, the wind might be blowing at different speeds and from different directions all along the way to your target. With the right-field topographical conditions, it’s entirely realistic that the wind may be blowing in one direction at your shooting location and in the opposite direction at the target. That makes it difficult to feed your ballistic computer reliable information.

In the bible for aspiring long-range shooters, The Ultimate Sniper by Major John L. Plaster, Plaster quotes a distinguished rifleman. “A plinker studies trajectory tables; a master studies the wind.” The better you can estimate wind speed and direction at various points between you and your target, the more likely you are to get a hit.

Adjusting for Wind

Step one is to use the math that some smart ballistic mathematician has already done. Earlier in the series, we talked about ballistic computer options. You can use a smartphone app and manually enter wind speed and direction relative to the shot to get a windage adjustment solution. Of, even easier, the Kestrel discussed previously will do all that for you.

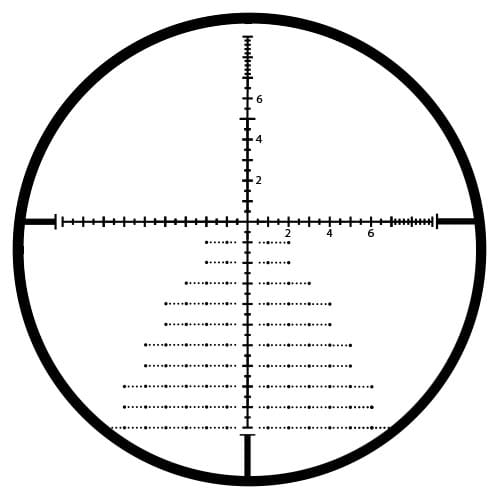

Whatever the method, you will need to adjust or hold a certain number of mils or minutes of angle to either of your target. Many long-range scopes feature exposed “tactical” or “target” turrets that are suitable for quick shot-to-shot adjustments in the field. This works excellent for elevation since gravity is stable and doesn’t change second to second. Wind, on the other hand, is continuously changing, so you may not have time to make a turret adjustment before the wind shifts or gusts again.

While definitely a user and situation preference, many prefer to use reticle hold adjustments for wind while using turret adjustments for elevation (bullet drop) adjustments. With the right reticle, you’ll have hash marks moving out to both sides from the center crosshairs so you can easily hold for the correct windage adjustment. With the right reticle, you can hold for both windage and elevation, but it gets trickier as the reticle is far more complex if you want to do it accurately.

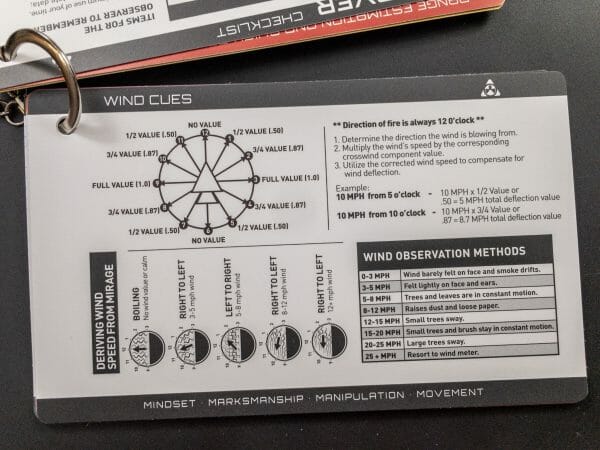

Directional Wind Values

A 90-degree crosswind will have more impact on bullet drift than wind crossing the bullet’s flight path at a narrow-angle. Of course, you could fill a notebook with every possible wind velocity and direction with observed bullet drift results, but that would be cumbersome, to say the least.

A more practical approach is to use established “fudge factors” that will get you close. Unless you were born after the invention of the iPhone, you’re probably familiar with a clock face and indicating directions by the numbers on the dial. For example, the wind coming towards you from just a little left of dead ahead is said to be blowing from 11 o’clock. Wind moving perpendicular to the direction you’re facing is coming from 3 o’clock. You get the idea.

So, here’s how the fudge factor works. You figure out and record the performance of your rifle and ammo combination for a 10-mph straight crosswind. That’s coming from either 3 or 9 o’clock. Once you have those bullet drift numbers for common distances, you can apply fudge factors for when conditions are different. There are two big variables at play.

First, the wind may be more or less than 10 mph. No worries. If it’s a 5 mph wind coming from 3 or 9 o’clock, just halve your adjustment. If you have to hold or adjust your scope turrets 1.5 mils for a 10-mph wind, just use .75 mils if it’s only blowing at 5 mph. If it’s blowing 20, and you are skilled enough to take a shot in those conditions, adjust 3.0 mils.

While wind speed allows proportional adjustments, be aware that distance does not. Unless it’s completely coincidental based on a specific ballistic profile and range scenario, the adjustment for 1,000 will not be double the adjustment for 500 yards. Remember, once it leaves the barrel, a bullet continuously slows down. The farther it travels, the slower it goes. The slower it moves, the more impact a given wind will have on its flight path. So, you’re more likely to see that more than twice as much adjustment is required when you double the distance to the target.

The second variable is wind direction, and this is where the clock concept comes into play. You assume that your perpendicular 10 mph wind adjustment is “full value.” For wind blowing from other directions, like 5, 11, or 6 o’clock, you’ll assign an adjustment factor because you’re not getting the full effect of the crosswind. The closer the angle is to directly in front of or behind you, the less you must adjust for wind, so the fudge factor is smaller. Here are the numbers from Magpul’s system. You’ll notice that the factors will vary a bit from different sources, so as you get serious about wind adjustments, do some of your own verification. These numbers will get you close, however.

- 12 and 6 o’clock: No adjustment. The wind has no sideways component, so your bullet won’t move left or right, at least not because of wind.

- 1, 5, 7, and 11 o’clock: ½ value. Multiple your 10 mph figures for a direct crosswind by half. You’ll notice that the angles of these four directions are the same. For 11 and 1 o’clock, the wind is coming towards you. For 5 and 7 o’clock, the wind is coming from behind. In both cases, the sideways bullet drift will be the same.

- 2, 4, 8, and 10 o’clock: ¾ value. Since these angles are a bit closer to perpendicular to your shot direction, the wind will have more effect.

- 3 and 9 o’clock: This is the scenario you planned for, so make no adjustment other than for wind velocity as outlined previously.

If you want to make all of this easy, pick up the Magpul CORE Precision Rifle Databook we discussed last month. It’s got handy cheat sheets for this and other wind-related scenarios.

About

Tom McHale is the author of the Practical Guides book series that guides new and experienced shooters alike in a fun, approachable, and practical way. His books are available in print and eBook format on Amazon. You can also find him on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest.