Hounded Leopard Hunting

Presented by Cheyenne Ridge Signature Lodge

Columbia, SC –-(AmmoLand.com)- The hound music swelled to a yelping intensity as the pack gained on the leopard.

Then, from deep in the Namibian brush came a loud, snarling cough. The moment of truth was finally at hand. The next few minutes would end the affair one way or the other.

My African adventure began to take shape when I asked Frank Cole of Cabela’s Outdoor Adventures to arrange a leopard hunt with dogs. I have never really enjoyed still-hunting the big cats from a blind. To me, hunting a leopard with hounds seemed much more exhilarating and exciting.

Cole contacted Barry Burchell of Frontier Safaris who proposed a 15-day leopard hunt at Trudia Game Ranch in northern Namibia, just south of Etosha National Park. They had never hunted leopard before on the ranch, but judging by the number of tracks, the big predators seemed abundant.

After a long but uneventful flight, I arrived at Windhoek where Barry then drove us 300 miles north through rocky, semi-arid hill country covered with low brush and stunted trees. It was late September and while the nights were cool, each day the temperature would climb to 90 degrees or higher by mid-afternoon, forcing us to do most of our hunting in the morning. To avoid dealing with the problems of transporting a firearm, I used Barry’s Remington Model 700 in 7mm Mag.

At the ranch I met Roy Sparks who had brought his pack of bluetick and treeing Walker hounds. An experienced hunter, Roy devotes most of his time to training his hounds and pursuing predominately livestock-killing leopards. Two other members of our entourage were Moshile, a Zhosa tribesman who is an extraordinary tracker and dog handler, and Alex, a tracker.

The first afternoon we drove along woodland roads looking for leopard spoor. Constantly harassed by ranchers, the area’s cats are wary and seldom come to bait, though we decided to hang two gemsbok baits just in case.

At 4:30 the next morning we began hunting in earnest. Our approach consisted of Moshile and Alex riding on the hood of the Land Cruiser using a spotlight and the vehicle’s headlights to search for leopard tracks as we slowly drove along the sand roads. They found a number of prints several days old as well as where a leopard had marked his territory with scent and scat. After driving about six miles, Moshile and Roy seemed quite satisfied that a large tom was in the area.

We quit at 11 a.m., then returned five hours later without the dogs. After hanging several more baits, we spent a couple hours scouting for leopard sign in a different area.

The next morning was a repeat performance of the previous days’ events. We found the remains of a gemsbok killed by a large leopard about two weeks earlier, but we failed to find any fresh tracks and none of the baits had been touched.

Early in the morning on our fourth day, after we’d passed all of the uneaten baits and moved toward one end of the area the big male had been using, the situation changed abruptly. Moshile raised his hand, and smiling broadly, signaled to stop the truck. Fresh tracks! – at least that’s what Moshile and Roy decided.

I had a hard time making out the tracks even when they were pointed out to me.

Moshile and Alex began following the leopard’s trail along with three hounds outfitted with tracking collars. Moshile carried a radio to keep in contact with us. He called no more than ten minutes later, indicating that he’d found a fresh track in a dry stream-bed. About that time one of the dogs opened up from a brushy ravine on the opposite side of the riverbed.

Over the next hour the trackers walked up the depression for nearly a mile, with the hounds sounding off more and more frequently. At this juncture, Roy released another hound that opened up almost immediately. Roy smiled and explained that the dog would bark only when on a fairly hot track.

All the hounds were giving tongue as they unraveled the leopard’s trail. After moving the vehicle twice to keep ahead of the pack, we heard Moshile’s excited voice on the radio. He’d seen the leopard! Roy stopped the truck and dropped the tailgate so the remaining six hounds could join the chase.

A sign on the truck – “When the tailgate drops, the B.S. stops” – was prophetic.

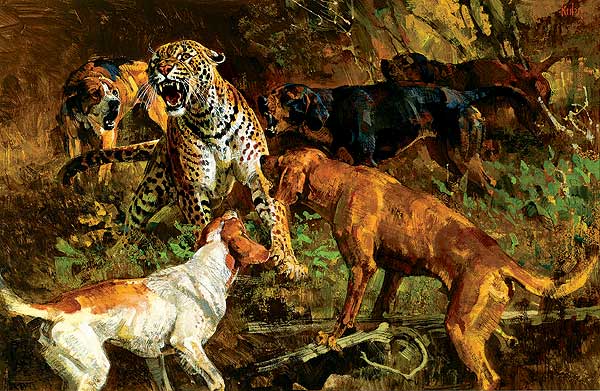

Rather than going up the hill behind us, the leopard turned in our direction. For the next ten minutes the air was filled with hound music. Then, some 200 yards to our left, the hounds finally bayed. The rasping snarl of the leopard, which had taken his stand on the ground rather than in a tree, was quite audible.

As we hustled over to the hounds, I began to experience a rapid heartbeat. It’s a problem that occurs infrequently, but when it happens, my heart rate zooms to more than 160 beats-per-minute. For a few seconds my condition left me feeling quite woozy. Then I thought, The hell with it, and taking a deep breath I hurried toward the fracas.

We moved closer to the dogs, but we couldn’t lay eyes on the leopard. The big cat moved off another hundred yards and stopped again, mad as hell and growling constantly at his tormentors. When we had slipped to within 30 yards of the leopard, I could just make out a patch of yellow just beyond a black-and-white hound named Charlie. In the thick brush, all I could see was the leopard’s body; the head and tail were not visible. I eased the rifle onto the shooting sticks and waited.

After a minute or so Charlie moved so I had a clear view of the cat’s chest. My shot was greeted with a loud growl. The leopard lurched to his left and disappeared in the dense brush, though the continued baying of the hounds convinced us he was still close.

We walked over to the dogs; Barry in the middle, Roy to his left and myself about two yards to their right and slightly to the rear. Barry, who is quite tall, saw the cat lying on his left side, barely breathing, no more than eight yards away. From my position I was unable to see the leopard.

“He’s dying,” Barry exclaimed. “No need for us to shoot again.” The leopard disagreed.

Without uttering a sound, the leopard suddenly stood up – silent as death – and charged hell-bent in Roy’s direction. Instantly the air was filled with a hail of gunfire. I saw the charging leopard just as he piled up less than two yards in front of Roy. The hunt was over!

It wasn’t until then that I noticed my rapid heartbeat was gone, replaced by a thrilling sense of achievement.

Interestingly, unlike the hounds used to hunt raccoon and hogs in the U.S., Roy’s dogs only sniffed at the carcass and showed no interest in chewing on it. Maybe they’d learned that mixing it up with even a supposedly dead leopard could be hazardous to their health.

While reliving the final, dramatic moments, Barry confided to me that he’d made a big mistake, dictated primarily by his desire not to puncture the leopard’s skin with too many holes. I’m sure he won’t refrain from shooting a “dying” leopard in the future.

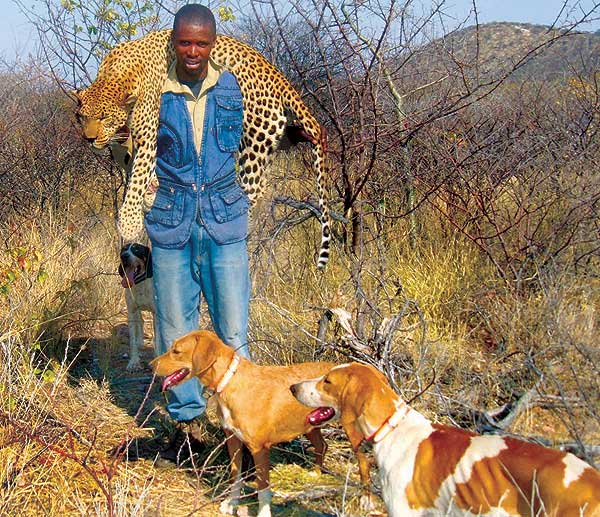

Moshile picked up the heavy leopard, draped him around his shoulders and walked back to the truck where he laid the majestic animal over an uprooted tree. The leopard measured seven feet, five inches from nose to tail, and Roy estimated his weight at 165 pounds – a very large male. Later, while skinning the cat, we found where my bullet had penetrated through one edge of his heart, filling his chest with blood.

How he managed to stay alive long enough to charge his pursuers remains a mystery.

The hounds came through the fracas generally unscathed. Several had fairly deep scratches and one had been either bitten or clawed on his leg. However, the bleeding had stopped and he seemed oblivious to the wound.

All in all, it’s certainly possible to have a more exciting leopard hunt, but our adventure was enough to last me a lifetime.

About:

Sporting Classics is the magazine for discovering the best in hunting and fishing worldwide. Every page is carefully crafted, through word and picture, to transport you on an unforgettable journey into the great outdoors.

Travel to the best hunting and fishing destinations. Relive the finest outdoor stories from yesteryear.

Discover classic firearms and fishing tackle by the most renowned craftsmen. Gain valuable knowledge from columns written by top experts in their fields: gundogs, shotguns, fly fishing, rifles, art and more.

From great fiction to modern-day adventures, every article is complemented by exciting photography and masterful paintings.

This isn’t just another “how to” outdoor magazine. Come. Join us! Visit: www.sportingclassics.com