Tom McHale answers, what handgun caliber is best for concealed carry?

USA –-(Ammoland.com) “It’s not the size mate, it’s how you use it.” ~ Nigel Powers, Super Spy Austin Powers in Goldmember (2002)

Wise words for a comedy movie and certainly relevant to the never-ending handgun caliber wars.

- What caliber is best for concealed carry?

- If I use a 9mm, won’t the bullets just bounce off my attacker?

- If I choose a .45 ACP, is there a chance that I might inadvertently destroy nearby buildings?

- Which buzzwords do I have to consider? Knockdown power? Stopping Power? Incapacitation? Penetration? Constipation?

When we start talking about all this stuff in theory and spice it up with Vietnam anecdotes, we cause ourselves a lot of unnecessary grief.

“When I was in ‘Nam, Charlie snuck into my foxhole one night. I plugged him with one shot from my 1911 and it knocked him 123 feet in the air right into a low flying F-105. After that, .45 is the only caliber I’ll use.”

OK, so maybe I’m making a bit of light about the value of anecdotal data, but anecdotes are exactly part of the problem in the great caliber debate.

- “I heard…”

- “I saw a Youtube video of a guy getting shot and he didn’t even know it.”

- “I saw a youtube video of a shooting and the guy fell down after the first shot.”

- “When I shot that deer, it cartwheeled 17 times.”

And so on.

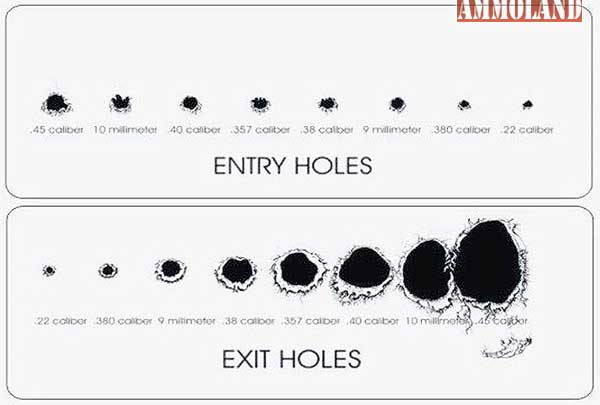

There are far too many variables at play to compartmentalize ammunition effectiveness into nice little mathematical buckets. Handgun bullets make holes. No more, no less. Some holes are slightly bigger than others, but when you really start comparing diameters of the popular handgun calibers, we’re not talking orders of magnitude of difference.

Let’s consider the range of self-defense calibers from .380 ACP to .45 ACP.

If we’re talking about unexpanded bullet diameter, common self-defense projectiles range from .355 to .451 inches. That’s a difference of only 0.096 inches. That’s less than the thickness of two pennies. If we’re talking expanded bullet diameter, assuming 1.5x expansion performance, then the range is .5325 to .6765. That’s a difference of 0.144 inches, which is the same as a penny stacked on a nickel. Yes, bigger bullets make bigger holes, but I mention these numbers to put things in perspective. A small fraction of an inch diameter wound channel difference isn’t all that significant in the context of a six-foot-tall, 200-pound irritable bad guy.

When it comes to energy or the ability to destroy tissue, an “average” 9mm defense load might deliver about 400 foot-pounds at the muzzle. An “average” .45 ACP defense load would unload about 425 foot-pounds. While that may sound like a lot, it’s not.

If you consider momentum, the ability to penetrate and move things, a 9mm load will present about 21 lbs-ft/second and a 45 will deliver about 30 lbs-ft/second. That level of pure momentum is roughly equivalent to hitting someone with a gallon of milk moving at three and a half feet per second.

Before folks get all upset, I’m not equating getting shot to getting bonked with a flying milk carton. While the milk will make a big mess, it’s not going to kill you unless you bought it on sale at Food Lion. My only point is that handgun bullets just don’t have all that much pure energy – at least not enough to make people fly across rooms and explode. They hurt, they can incapacitate, they wound and they certainly can kill, but they won’t physically launch people through walls and windows like in the movies.

When shot, living things may fall, jump, collapse, spring backward, jump, flip or do nothing at all. The important thing, to note, is that none of these actions, with the exception of the “nothing at all” choice, are a direct result of the energy and momentum of the projectile. These reactions can be the result of pain, fear, conditioned response (people are supposed to fall down when they get shot), damage to those bodily systems that keep us balanced and standing, or a million other things.

A scientific look at things like bullet diameter and energy seems to indicate that 9mm and .45 ACP (as examples) are not really all that different. What about actual performance as measured by actual shootings? Do certain calibers create dramatically different results in lethality or the ability to quickly incapacitate? Again, we have to set anecdotes aside. For every story of a guy who flew 10 feet backward when getting shot, there’s another story of some other guy who didn’t even react to getting shot – and kept fighting.

We can get some statistical indication of caliber performance from looking at compiled data of actual shootings, but we even have to interpret that with a grain of salt. In a pure statistical model, all variables are carefully controlled. In real world shootings, there is no such thing as variable control. People are different. People are moving. Shots impact in different places and from different angles. Some people feel pain. Others are on drugs and temporarily impervious to pain. But even with all that said, there’s some interesting data about caliber performance available.

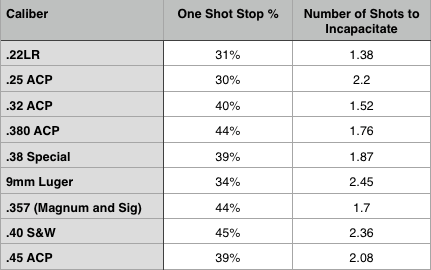

I recently read an interesting article by Greg Ellifritz published on the Buckeye Firearms Association website. Over a 10 year period, Greg collected data on actual shootings and categorized a number of things like the lethality and one-shot stop percentages by caliber. Greg developed “rules” on how to consider the raw data and establish some level of variable control – I’ll let you review that in his findings. For purposes of this article, I’ll offer his observations for one shot stops.

As a concealed carry holder, I’m not interested in anything but stopping whatever violent action caused me to draw a gun in the first place.

This is one look at historical data, but other studies show similar results. There’s not a tremendous difference in performance between common calibers. Listening to caliber selection arguments, one might expect some calibers to be 38 times more effective than others, but it’s just not the case.

So what’s my point? The table above is most definitely NOT a guide to caliber selection. Just because one caliber shows higher one shot stop percentage or fewer hits per incapacitation doesn’t mean all that much. As I mentioned earlier, there are simply far too many variables at play to ever make absolute judgments like that.

If there is a point to be made, it’s right there in front of us in the numbers. Consider the number of shots to incapacitate. Not how many, but the fact that you have to have hits in the first place. Choose whatever ammo you’re comfortable with and spend more of your energy developing the skills to make hits when you need to, and less arguing about which caliber is the “magic bullet.”

If you want an interesting read, check out this FBI article on Handgun Wounding Factors.

Handgun Wounding Factors and Effectiveness

About

Tom McHale is the author of the Insanely Practical Guides book series that guides new and experienced shooters alike in a fun, approachable, and practical way. His books are available in print and eBook format on Amazon . You can also find him on Google+, Facebook, Twitter and Pinterest.