The author finds the Henry AR7 Survival Rifle easier to shoot when placing your support hand over the magazine well rather than under the barrel. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

Today’s modern gun owner takes a lot into consideration when it comes to tactical and survival applications. We tend to shun older designs in exchange for the latest high-speed, low drag development. But this isn’t anything new. In the U.S., it started with the realization that the expensive rifle couldn’t get as much done as the humble smoothbore musket, when tactics and survival were everything.

In terms of guns built specifically for survival applications in mind, the single-barrel shotgun and the .22-caliber rifle reign supreme. Among compact .22 rifles, the AR7 will bring on a suggestive eyebrow raise.

A spin off of a USAF survival rifle from the early 1960s, Armalite produced this collapsible .22 auto-loading rifle for some time until Charter Arms bought the design. Decades on, Henry Repeating took up production of the rifle. So, what is the AR7? To put it simply, it is a light-weight eight-shooter that breaks down and stores in the buttstock for safekeeping. The rifle was meant to be a light-weight camping companion and a convenient tool for survival when the stars align and the user is at the world’s mercy.

Henry’s U.S. Survival Rifle

I’m not a huge fan of auto-loading .22 rifles, but I am a massive James Bond fan. So, I was tickled by the little rifle when I saw the original Armalite AR7 being used to assassinate Bulgarian killers and dispatching of a Spectre helicopter in From Russia With Love. Eventually, I got my hands on the new Henry mode.

The AR7 rifle fits in the stock. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

When I first took the rifle out of its cardboard box, all I got was the buttstock. Luckily, all the other parts were inside the stock – like they should be. I popped open the plastic buttplate and poured out the contents – the barrel, two magazines and the receiver.

At first glance, the rifle looked like a plumber’s first foray into firearm design. Big holes, tubing and threads aren’t what most of us are used to seeing in a rifle.

The magazines are made of stamped steel and hold eight rounds of .22 LR ammo. The aluminum receiver is squarish in appearance and locks into place via a captive wing screw that is in the pistol grip of the buttstock. Tighten it down then put on your barrel. There is a key that lines up with a corresponding slot in the threads at the front end of the receiver. Guide the steel barrel nut over the threads and screw it down by hand until it is taught. Voila. An assembled rifle and boy does it look awesome – and crude at the same time. On the first go, the receiver and buttstock had some play that required a pair of pliers to torque the wing nut for a tight, sturdy fit. After this initial trouble, I had no issue assembling the rifle smartly with finger pressure.

Fully assembled, we have a functional semi-automatic .22 rifle ready for work and weighing in at only 3.5 pounds. The gun is blowback operated and relies on a heavy bolt and spring pressure to operate properly. To operate the bolt, there is a small cocking handle that can be pushed in to store the rifle in the buttstock.

The barrel is 16-inches long and is essentially a steel sleeve enclosed by a polymer shroud, rather than an aluminum shroud found on the original Armalite design. The sights on the rifle are a front, orange plastic blade and a rear peep sight that is adjustable for elevation. There are two peeps, one for short distance and quick sighting and a smaller peep for longer distances. It is switched out by loosening the screw holding the peep blade and turning it 180 degrees in the slot to expose the other peep. The receiver has a rail that will take an optic, but if you choose to use an optic on the receiver, it cannot be stowed into the buttstock.

The buttstock, by the way, is made of hard plastic and is designed to be water resistant. The rifle has a manual safety catch on the right side behind the cocking handle. The Henry Survival Rifle can be had at the $300 mark in black finish, true timber camo, and my version – viper western camo.

On the range

A .22 rifle has a lot of merit for survival. The guns and the ammo are very light compared to anything else, which means they can be packed in without much notice, and the .22 LR cartridge out of a rifle has enough power and accuracy to take small game with ease.

The AR7’s weight and the compactness seemed perfect. I felt like a true spy assembling the rifle virtually out of thin air. Since this is the rifle can’t be stored properly disassembled with a scope, I decided to hit the range and test the rifle with the stock iron sights in a dual accuracy and durability test.

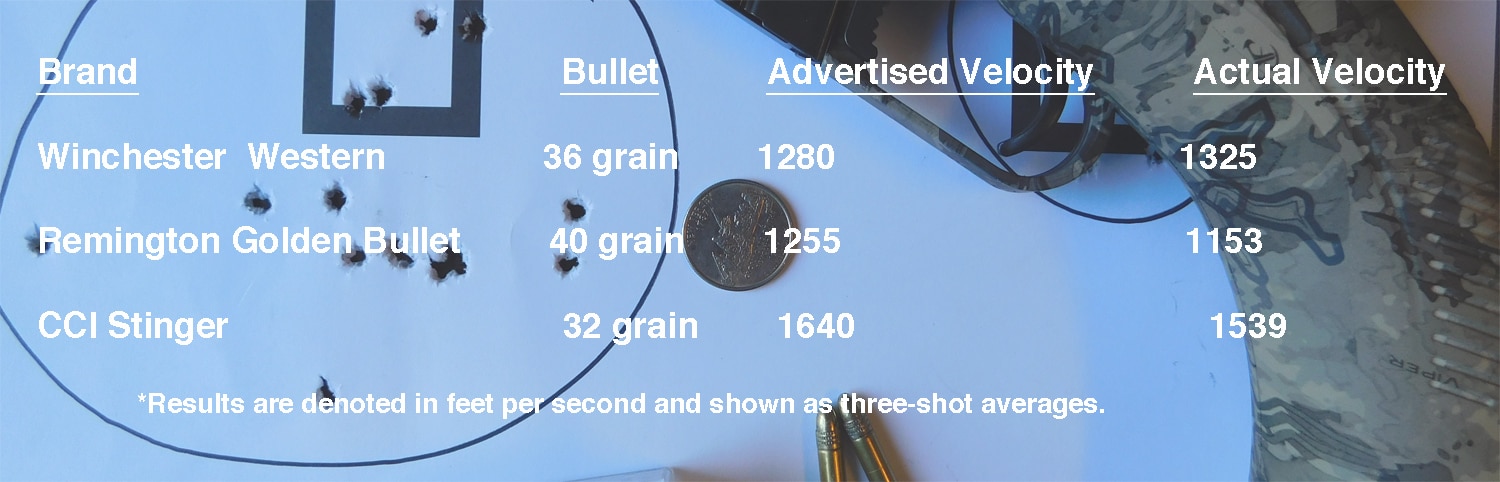

But first I had to know just how much power we are talking about. With the Caldwell Chronograph plugged in from 10-feet away, I fired my two-primary test ammunition — Winchester Western 36 grain hollow-points and Remington Golden Bullet 40 grain round nosed bullets. I also had a few CCI Stinger 32 grain hollow-points that I sent downrange as well.

(Graphic: Terril Herbert/Guns.com)

These numbers don’t mean a whole lot, considering we know the .22 LR is a small-game number of the first order. But seeing the capabilities could be useful. A CCI Stinger might work well if you are forced to shoot down a big animal, but would blow apart a squirrel with not enough left to eat. It is also of note that the AR7’s bolt spring is tough. It, like most semi auto .22s, won’t play well. It is recommended that high velocity ammunition be used in this gun for that reason.

With the gun fully assembled, loading is accomplished by inserting the eight-round magazine into the receiver well and pulling back the telescoping charging handle on the right side of the bolt. Let it go to chamber a round. Flip the safety catch back to disable the trigger until you are ready to shoot.

A difficult aspect of this rifle is figuring out how to hold it with your support hand. Holding onto the barrel works alright, but I found gripping around the magazine well to be more comfortable. It takes some thought because a conventional style of grip might put your fingers in the path of the ejecting cases, potentially injuring the fingers or inducing malfunctions. It is also worth noting that the design of the stock has the receiver and barrel offset to the right side. This may require some shooters to put more cheek on the comb of the buttstock to look through the sights, but in both my left handed and right-handed testing, shouldering and aligning the sights was effortless. These issues are more akin to a symptom of being so portable than being actual flaws.

I started my test with mag dumps, which took quite a bit of time as the two magazines only hold eight rounds a piece. The Winchester Western rounds did well in the course of a 150-round battery of mag dumps, but the semi-wadcutter profile of the bullet could cause problems when it comes to feeding – and on two occasions I did have rounds hang up in the ejector port, unable to feed into the chamber.

When packed in the stock, the rifle will float. However, Henry does not guarantee that it will float. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

I followed that up with 100 rounds of Remington Golden Bullet 40 grain rounds. This round-nosed offering fed reliably in the rifle, but I had two failures to fire — dud rounds. I found the Remington offering to be a little more accurate — though not by much. I loaded up the magazines with this round and tried for accuracy.

Standing, I was able to put eight rounds into a 1.5-inch group at 25 yards, a typical woodland small game distance — though quite close for any big, leery animals you might hope to take in a survival situation. I fired a group of 16 shots, rapid-fire, and was able to cover the 25-yard target in a constant group at the point of aim that encompassed the palm of my hand. Up close, the Henry Survival Rifle is more than adequate for dusting off small game or getting the lead out in a potential self-defense situation.

At 50 yards, things didn’t pan out like I had hoped. This time, I set the rifle on my usual impromptu rest — my ammo can. I took a seat and tried to work on a good group. The front sight at this distance is increasingly thick against a 12-inch bullseye target. My 50-yard groups landed a few inches lower than the point of aim — without adjusting the sights from the 25-yard test. The group size was what was important and I honestly expected better than the consistent four-inch groups I shot.

Thumbs up, thumbs down

The Henry AR7 is a very popular rifle and with good reason, but there are a few things that did bug me I would like to get out of the way right now. One is a bit of a deal breaker and another is more of a personal preference.

The big deal breaker is the safety catch on the rifle. I think it could be more of a liability than an asset on a survival themed gun. It is easy enough to flick on and off one handed and it is positive, but after doing magazine changes, the safety has a thing for switching to the “safe” position when I don’t want it to. This isn’t a problem for hunting purposes but if you are working quickly under stress, that could be a deal breaker.

While we are on the subject to tactical reloads, I found the telescoping charging handle to be harder to work with than I imagined. I thought it would remain projecting from the bolt until I pushed it in for storage. Granted, it needs to come out for manipulation and field stripping the gun, but the handle hides at the surface of the bolt. Not what I was expecting and I had to go fishing to grasp it. For survival, this isn’t a bother at all, but it might be harder to grasp and pull out in very cold weather.

With that said, the strengths far outweigh any real issues. Over quite a few .22 autoloading rifles, the AR7 is still a straightforward, trustworthy performer. The power and accuracy is sufficient for the most likely protein you will find at any time of the year in nearly habitat — small game. Though the accuracy suffers slightly due to the rifle’s light weight, the rifle’s portability is what makes it so great. It can fit in a backpack with ease and comfort. For plinking, the rifle is lightweight enough for a child to enjoy but still handy for a stranded person to use—even one handed. Though a gun is only one small part of a survival kit, the Henry AR7 leaves little to be desired within its realm.

The post Gun Review: The Henry AR7 Survival Rifle appeared first on Guns.com.