Russian firearms are a lot of things: crude, quirky, utilitarian, behind the times, perhaps even a good buy. The Mosin-Nagant rifle and the later AK-47 won’t win any beauty contests. Neither would the Makarov pistol of Bond film fame, being little more than a crude Walther PPK knock-off. Another curious pistol in Russia’s 20th century arsenal is the m1895 Nagant revolver — a handgun that was innovative, yet obsolete on the same coin. A handgun so interesting I just had to buy it not once, but twice.

A touch of history

Despite its primitive look, the 1895 Nagant has a nearly unrivaled service history. That story started in the early 1890s when autocratic Russia was seeking a new handgun to replace its 44 caliber Smith & Wesson break-top revolvers. Emile and Leon Nagant, who were known to the Czar for their work on the magazine system on their recently adopted M91 Mosin-Nagant rifle, had a solution in mind.

My Nagant was made in 1944 at the Izhevsk arsenal during World War II. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

Nagant revolvers had already been adopted by a number of countries, but this new Russian revolver featured a few upgrades that impressed the Czar. In particular the use of a gas-seal cartridge. Originally, this new revolver, picked up in 1895, was produced in two models: a double action officer’s model and a single action model for the lower ranks.

The Nagant revolver would be Russia’s primary sidearm through World War I and was arguably the gun used to execute the Czar himself when the Russian revolution reached its fever pitch as the Bolsheviks strengthened their grip on the country. In true Communist egalitarianism, the two Russian arsenals, Ishvesk and Tula, produced only the double action model from 1918 onward.

The end of the brass case is longer than the cylinder, allowing it to project into the barrel itself, creating a gas seal when fired. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

Soviet Russia eventually went with a new self-loader, the famous Tokarev pistol in 1933. However, the Nagant handgun was still a prime weapon throughout Russia’s titanic struggle against Nazi Germany during World War II. Production did not end on the Nagant revolver until the war had ended in 1945 and both the Tokarev and Nagant were phased out with the introduction of the Makarov pistol in 1950.

Still the Nagant’s legacy continued. It was exported to various Soviet republics as well as to the Chinese and Vietnamese Communists as war aid. Furthermore, the gun would see service as a Russian police arm and terrorist cache hold over into this century.

Features

With such a long history of use, it is surprising just how primitive the 1895 Nagant really is. All in the same, the Nagant embodies late 19th century attitudes toward service pistols in general.

The Nagant is a solid frame revolver that is not all that dissimilar looking from its contemporaries like the Austrian Rast & Gasser or the French 1892 Ordnance revolver, except cruder.

The camming block that pushes the cylinder forward for firing. This is in part to blame for the heavy trigger pull of the gun in double action mode. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

You are apt to find more milling marks on an average Nagant and perhaps even a sharp corner than on other era revolvers. The few screws used in the gun’s manufacture are sitting proud as well. The sights are typical for military handguns of the time with a rudimentary milled notch on the top strap of the frame and a front blade sight that can be adjusted in its dovetail. The gun isn’t necessarily a boat anchor, weighing in at just under two pounds and sporting a handy, tapered 4.5 inch barrel.

Like other military revolvers of its time, it chambered a relatively new, small-bore cartridge, the 7.62x38R or 7.62 Nagant round. Unlike most ammunition, however the bullet is seated completely in the case.

The Nagant loads and unloads through a loading gate on the side of the pistol. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

The Nagant loads and unloads via a loading gate on the right side of the fluted cylinder and uses an ejector rod housed under the barrel to punch out the empty cases. The gun holds seven shots and has a transfer-bar like safety as well as a rebounding hammer to prevent the gun from discharging if dropped.

Unless you have a rare single-action model, the Nagant can be fired by either pulling the trigger all the way through or cocking the hammer spur then pressing the trigger. The act of pulling the trigger or cocking the hammer manually is tougher than on most revolvers because of its gas seal design.

The sights are typical for the time, but not useless. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

A steel block pushes the cylinder forward when the hammer comes back, forcing the recessed chamber over the forcing cone. This, combined with the cartridge that sits higher than the chamber mouth, eliminates the cylinder gap. We know now that the Nagant is one of the few revolvers that can be shot with a suppressor to deaden the sound. Naturally this was not the thought process of the time as suppressors were in their infancy when the m1895 was developed.

A note on ammunition

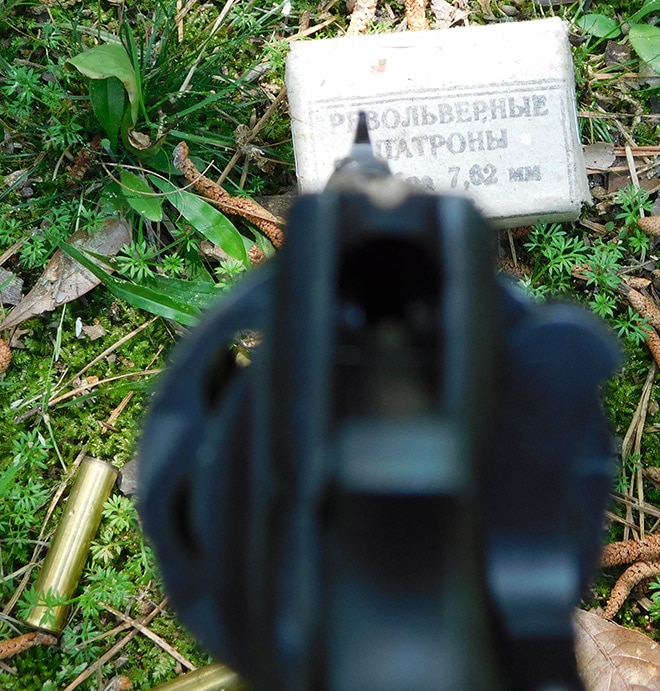

The biggest concern with owning a Nagant revolver is finding ammunition. Military surplus ammunition is one, dwindling option. Readily available 32 S&W Long cartridges may be used in the Nagant, but the gun is not intended to use such ammunition. Factory offerings for 7.62mm Nagant are restricted to mostly Fiocchi and Privi Partizan brands. I assembled a bit of everything when I finally got my hands on a 1944 war-time produced 1895 Nagant and headed to the range for a blast from the past.

The test ammunition. All shot well, though power goes handily to the surplus ammunition (right). (Photo: Terril Herbert)

On the range

The Nagant revolver has a Victorian-esque mystique to it, but the gun will still shoot. Loading the pistol is accomplished by opening the loading gate on the right side and dropping in a cartridge. Manually rotate the cylinder and repeat until the cylinder is full. You get seven shots instead of the usual six. Close the gate and get to firing.

The hammer spur, though well checkered and well in the open, takes a little effort to cock considering all of what is going on mechanically in comparison to a usual revolver. The trigger pull with the hammer cocked in single-action is quite crisp with no movement except for the trigger breaking — but it takes a good ten pounds to break that trigger. You will face about the same effort to fire a modern revolver in double action.

The smaller case of the 32 S&W Long means the round is not long enough to use the gas seal feature. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

As you may have guessed, the Nagant’s double action trigger pull is even worse. It exceeded my Lyman scale and felt twice as heavy as the single action pull. It does, however have a definitive click when the firing block pushes the cylinder forward and the trigger gets easier toward the end. The effort it takes to both cock the hammer, rotate the cylinder, push that block forward to advance the cylinder forward against the barrel, then break the trigger is, in one word, horrendous. Some shooters can’t even fire the pistol in double action.

The ammunition I used for my shooting sessions included: Fiocchi 98 grain FMJ 7.62 Nagant, Aguila 32 S&W Long 98 grain LRN, and Russian 7.62 Nagant surplus 108 grain FMJ ammunition.

The Nagant revolver, despite its heavy trigger pull is no slouch. With surplus ammo, I managed a 2.9-inch single action group, fired with one paw. More than good enough for target work or getting a small critter for the pot. The five inch double action group isn’t too bad either. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

All ammunition was 100 percent in reliability with no dud ammunition or hang fires, especially a concern with the military surplus ammunition which was made back in the 1970s. Recoil was non-existent with the Fiocchi and Aguila loads with a bit more muzzle flip using the surplus rounds, but nothing that could be felt in the hand.

Speaking of “in the hand,” the grip has a bag-type European grip frame with plastic grips and a lanyard loop on the bottom. It fits fully in the hand, but is not overly big. It is more comfortable than it looks, which is the same for pointing and shooting the Nagant in general, despite the hard trigger pull. Even with a bit of shaking trying to pull the trigger in double action, I can empty the gun in a hurry. However I spent most of my range time just cocking and shooting. When that devilish looking needle firing pin goes home, you know that round will be downrange.

I was a bit hesitant to group the pistol as my old Nagant revolver, made in pre-war conditions, was worthlessly inaccurate. Regardless, I decided to shoot both double and single action at seven yard. I managed to turn in a 2.9-inch group with the military fodder firing single action and just five inches in double action. The Fiocchi and Aguila ammunition did better in double action, but the single action groups widened just so slightly to three and 3.2 inches respectively. At 25 yards, it seems the Fiocchi did best with a single action group of six inches. All shooting was done, one handed.

Unloading — the most dreaded part of a Nagant owner’s life — goes as follows: Unscrew the ejector rod from under the barrel and pull it out then twist the ejector assembly to the right. Open the loading gate and punch out the empty cartridges as you rotate the cylinder. Though it is possible to push the case mouths of the Fiocchi cases and let them fall into hand, it wasn’t reliable doing so with the military ammo, whose cases got quite stuck at times. In fact, sometimes the military cases got so stuck it took a sharp smack against a solid object for the ejector rod to punch out a case.

Split cases are an uncomfortable reality when using 32 caliber revolver cartridges in the Nagant. Eye protection is a must. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

The 32 S&W Long, which has a smaller case than the Nagant round and is not long enough to use the gas seal feature, comes out violently bulged with some cases split open. Know the potential risks of brass fragments before using 32s in your Nagant.

While on the range, I decided to see how fast the Nagant could put lead downrange, partially out of routine and partially out of settling the myth that the 7.62 Nagant is a wimp round. So, I cranked out the Caldwell Chronograph, took a seat and put some bullets into the berm.

Ballistics

Russian 108 grain FMJ 1006 fps

Fiocchi 98 grain FMJ 628 fps

Aguila 32 S&W Long 98 grain LRN 576 fps

Note: Chronograph is 10 feet from the muzzle. FMJ= full metal jacket. LRN= lead round nose

After a bit of number crunching, the Russian surplus generated about 243 foot pounds of muzzle energy, outshining the 380 ACP and rising to par with standard pressure 38 Special energies. Fairly eye opening, in my view.

Parting shots

If there was ever a misunderstood military pistol, the 1895 Nagant is it. With inexpensive factory loads and some inexperience behind that heavy trigger, it’s easy to see why these revolvers are known for being powerless and only good for executing dissidents. Taken together with the slow loading and unloading process, one would think it would be suicidal to take a Nagant in combat.

Once I got to learn some about attitudes of the times and plenty of trigger time as well, things became clear.

The M1895 Nagant revolver can be found on the used market in the $400-$600 range. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

There were more powerful cartridges out in 1895 as were there swing-out cylinder handguns. But the Russians in adopting the Nagant just might have had the best revolver of its class. The gas-sealed 7.62×38 boasts more power than the French 8mm Ordinance or the Austrian 8mm Gasser. Additionally, swing out cylinders were not fully accepted at the time because of field reports of fouling getting under the ejector star.

The Russians went with what worked best. The spring-less ejector rod housed under the barrel was typical of the time as was the heavy trigger pull. It was common practice until “combat” revolver training of the 60s for revolvers to only be fired in double action in a close-range emergency.

The pistol in the early 20th century was primarily meant for officers and cavalry. The officer’s main job was to command, not to fight. The cavalryman’s main arm was the sword or the lance and the pistol was secondary. In other words, the features of the 1895 that we scoff at today were considered adequate for the job.

Despite my exaggeration of the loading and unloading process, the Nagant is still a solid performer, giving useful accuracy while boasting recoil that won’t bother a new shooter. The gun is straightforward to operate and reliability is like—well—a Russian revolver. Unless you handload the 7.62x38mm round, ammunition can be somewhat pricy or result in split cases. Any effort, in my opinion, to shoot the Nagant is worth it whether you appreciate history or want to turn that relic into something a little more useful.

The post Gun Review: Russian M1895 Nagant revolver in 7.62x38R (VIDEO) appeared first on Guns.com.