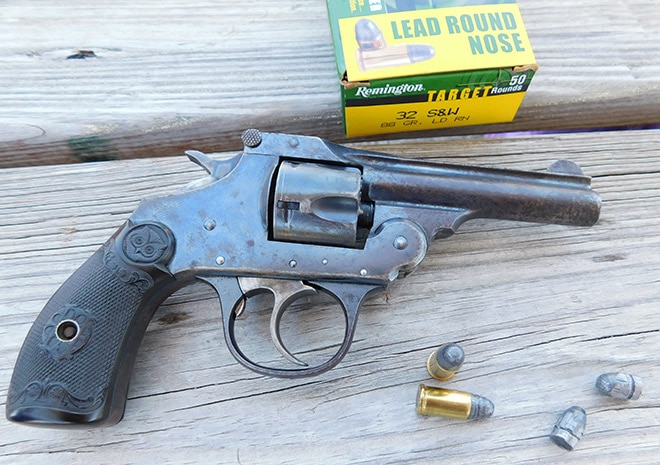

Iver Johnson Automatic Safety revolver with smokeless .32 SW rounds and 32 black powder bullets. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

What is innovative yet archaic and popular yet infamous? In the world of handguns, perhaps no firearm better illustrates this little riddle quite like the Iver Johnson Safety Automatic revolver.

My affinity for pocket pistols, both new and old, lead me to this gun. The topic is quite popular today given that, since the 1990s, the passage of concealed carry legislation and the production of small pistols to suit this need has simply exploded. As we leave the 20th century firmly in the dust, I want to look back to see what people were carrying at the dawn of the century we just left behind.

At the turn of the 20th century, openly carrying a pistol was practically impossible unless of course you were a member of law enforcement and there were no permitting systems in place. Despite that, carrying a small handgun in a concealed manner was a normal, but unspoken occurrence. Perhaps the most prolific and successful pocket pistol of the age was the top-break revolver.

In the early 1890s, small .32 and .38 caliber handguns were starting to show up on the market. Firms like Smith & Wesson made their modern reputation with guns like the “Lemon Squeezer”, a top-break five-shooter with a grip safety. Other companies made similar handguns — some good, some bad. But if any other company had a strong stake in the pocket revolver market, it had to be Iver Johnson.

The Safety Automatic

The history of Iver Johnson and their many revolvers could be the subject of a college dissertation. Suffice it to say, the company Iver Johnson rose to prominence making bicycles as well as firearms. Their weapons were expressly meant to fulfill the need of concealed protection in an era of high crime in America’s big cities during a time before concealed carry permits.

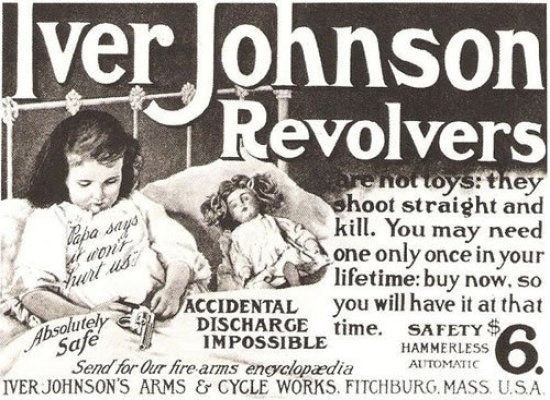

Iver Johnson’s marketing largely focused on the safety of their handguns over that of its competitors.

Developed in 1894, the Safety Automatic is not an automatic revolver. The word “automatic” refers to the safety mechanism. Imagine that.

That safety mechanism was a transfer bar system that kept the hammer from striking the frame-mounted firing pin unless the trigger was pulled. This was one of the first systems of its kind and Iver Johnson’s marketing campaign took to it, billing it as a safer gun that could not be accidentally discharged. This is the modern standard in revolver safety—but Iver Johnson was doing it over 100 years ago. A hammerless version of this handgun was offered and one model even included a trigger safety — much like the one Gaston Glock eventually used many years later.

Aesthetically, the guns are all steel with some being finished in blue and others in nickel. The diminutive grips on these guns are either wood or plastic and all feature some mild checkering along with the owl-head stamp that was Iver Johnson’s trademark at the time.

The owl-head icon on the plastic grips is a dead giveaway that we are dealing with an Iver Johnson revolver. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

These revolvers opened via a latch that rides above the exposed hammer. This allows the barrel and cylinder to be tipped forward. The automatic ejector raises up and runs back into its housing at the end of its stroke so you can load five rounds into the cylinder A young Oscar Mossberg helped perfect this system, which was both fast and straightforward — but also weak, hence the low powered cartridges that the gun fired.

The Safety Automatic was available in a small frame that chambered the 32 S&W or a larger frame utilizing the larger 38 S&W round. Neither cartridge was especially powerful, but they were short enough to eject easily and weak enough to be used in a top-break revolver, which relies on a small hinge to hold everything together when firing.

The sights on the Safety Automatic consists of two small posts on the top-strap of the action and a rounded blade near the muzzle. From the factory, different barrel lengths were available though today the 3 inch model is the most prevalent and as such weighs in at an almost unbeatable 12 ounces — lighter and smaller than most small revolvers and automatics available today. Well over one million of these guns were produced until production ended in 1941 with the onset of World War II.

If the sights look tiny and hard to see, it is because they are. The Safety Automatic was meant for close range self-defense. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

Selling for a fraction of the price of a comparable Smith & Wesson, the Safety Automatic was available to the common worker to put in his pocket or sock drawer in increasingly violent times. Unfortunately, the Safety Automatic was tainted by infamy when Polish-American anarchist Leon Czolgosz used one to assassinate US President McKinley in 1901, propelling the progressive minded Theodore Roosevelt to the White House.

Black powder or smokeless?

The French came up with smokeless powder back in 1885, but new rifles using the new propellant took priority over handguns. Hence, right up to the turn of the century, many handguns were designed around black powder cartridges, which have a lower pressure curve than smokeless.

Iver Johnson’s First Model has a single locking post that interfaced with the top-strap hinge. The Second Model, produced from 1896 to 1908, had a stronger double post setup. Both were produced in the hundreds of thousands, yet were never rated for smokeless powder. The Third Model looks nearly identical to the Second, but is beefed up to use smokeless ammunition. An easy way to tell a Third Model from the Second is its use of a coil spring to power the hammer. Also, the Third Model’s cylinder locks up at rest, while the other models have cylinders that spin freely, even when the hammer is not cocked. Naturally, all these guns are old and led hard lives. They should be carefully inspected before you decide to put bullets downrange.

From left to right: 22 LR, 32 S&W, 32 S&W Long, 38 S&W, 38 Special. Iver Johnson’s guns chambered the stubby 32 S&W and 38 S&W cartridges. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

Ammunition is still relatively available for the 32 S&W and 38 S&W round, owing to the vast quantity of small guns chambered in these rounds. Unfortunately, this is smokeless ammunition. If you have an older model, you will have to reload your own black powder rounds or dig deep online to get your gun running again.

On the range and in the gel

My Iver Johnson Safety Automatic in 32 S&W looks worse for wear, as do many of these guns. The blued finish is mostly gone and covered by old, brown rust. But mechanically, the gun is perfect and the bore is good. I found from taking off the grips and looking for a coil spring that mine is indeed a Third Model, so it is safe to use factory smokeless ammunition. With a box of Remington 88 grain Target ammunition, I set out to put the little gambler gun through its paces.

Loading the Safety Automatic is easy. Lift the knurled latch up and flip the barrel down. The automatic ejector pops up then cams down at the end stroke so you can load five cartridges into the cylinder. Close the gun until the hinge latch pops over the locking posts.

Loading the Iver Johnson is straightforward, but perhaps not as intuitive as a swing-out cylinder revolver. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

At first, with all the stories about poor workmanship in these revolvers floating around, I expected the little gun to blow up in my face. But when I squeezed the trigger all the way through to fire a quick five shot ammo burn, all I got was five resounding pops. Not bangs — pops. Puffs of smoke followed as did holes in my target. The owl-head grip dug into the web of my hand a bit with each shot, but I was out of ammo in no time. I was alive and so was the gun.

Unloading the gun is a snap—literally. Think of it as unloading an American Webley. Pop the latch and snap the gun apart briskly to send the cases flying.

Unloading is entertaining to say the least. Lift the hinge latch and snap the barrel forward smartly to send the empty cases flying out. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

Admittedly, the double action trigger pull is a solid 10 pounds and very stagy toward the end. You can predict when the hammer will fall back forward. Though this is not a Smith & Wesson, the trigger did not feel gritty while pulling. That could be a tribute to Iver’s workmanship or a century of work on the pistol’s part.

Shooting the gun in single action is a bit tricky. You must reach for a small hammer on a small, thin handgun. It is a little awkward. The trigger pull still felt stiff, but lighter in single action. I believe the pistol’s small size and especially the small trigger guard make things a little more awkward than one of today’s revolvers. I found it easier to hold the gun midway on the grip and fire in double action. The sights don’t help with accuracy much either. The rear sight is fixed to the hinge and is a small notch — a very small notch. The front sight is a fine, but more prominent half-moon blade. They do pick up well once you catch them, if you can see them.

The single action group took some work at seven yards. Four inches isn’t terrible, but the gun’s small size lends it better to double action shooting. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

Today, the Iver Johnson’s are not only thought of as being subpar with craftsmanship, but also accuracy and power. Not being able to shoot a bullseye at 7 yards in single action with one hand was a little disheartening. A 4-inch group is passable, but not great, though certainly good for decent sized pests. On a more open range, I could hit a half-sized D28 steel target at 10 yards with absolute regularity in double action.

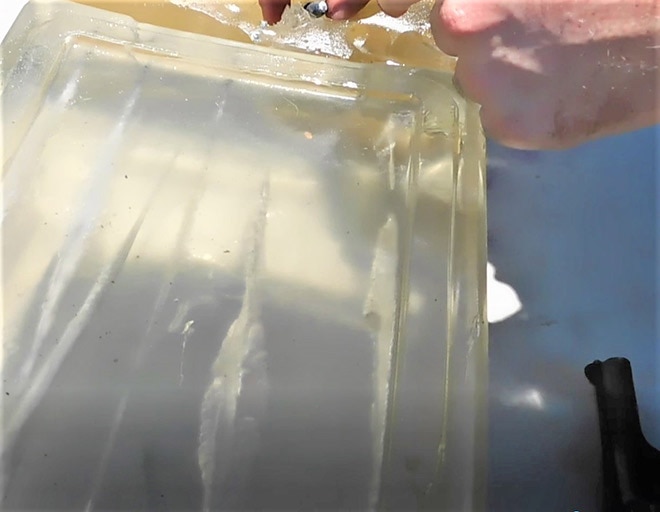

One of the wound tracts of the 32 S&W round. Even after going through four layers of denim, the wound path is straight and narrow. The round finally stopped fourteen inches into the block. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

As for power, my shooting partner and I tagged two blocks of 10 percent ordinance gel with the same Remington 88 grain lead round nosed bullets. Out of the trusty Caldwell Chronograph, these bullets are getting out of the Iver Johnson at an average of 660 feet per second. That’s only 85-foot pounds of energy — hardly better than the best 22 LR loads out of a small handgun.

Indeed, the 32 S&W has a poor reputation as a man stopper. But to our surprise, these bullets passed through four layers of denim and penetrated 14 inches into the gel. A follow up shot made it to the 18-inch mark with a mediocre, but straight wound tract. The 32 S&W certainly has the capability of ending a fight outright.

Wound cavitation detail of .32 SW. This “dinky” round would certainly end a fight. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

Final thoughts

Though I am one of the few secretly wishing for the snappy top-break revolver to make a comeback, it was easy to see that the Iver Johnson and others like it, were a dead-end design, even in 1900. The first hand ejector revolvers offered by Smith & Wesson and Colt had arrived. Browning had already introduced his first slide operated auto pistol. The future was there at that time.

Top break revolvers are neat, but they aren’t quite as natural to reload as a swing-out cylinder revolver that we are used to now and the solid frames can take much more powerful cartridges. In the auto world, guns like the Colt 1903 were popular and offered more rounds and a faster reload. Yet, the Iver Johnson stayed popular through the dangerous gangster era and the hard times of the Great Depression. It was inexpensive, yet extremely reliable. It was a simple weapon to use and a very safe one — one that pioneered safety features we rely on today. All the same, the Safety Automatic has claimed its fair share of lives, both criminal and otherwise.

Often for less than $100 you can buy a little piece of concealed carry history. (Photo: Terril Herbert)

When perusing online gun listings or the glass cases at mom and pop pawn shops, you can still find these lying around, often in a sorry looking state. The finish will be gone. The caliber is dinky by today’s standards. The Safety Automatic’s best days are long behind it. But in a collector’s market, you may be surprised at what you can get for a very low sum of money: a gun that is innovative yet archaic, popular yet infamous.

The post Gun Review: Iver Johnson Safety Automatic Revolver in 32 S&W appeared first on Guns.com.