By Joel R. Kolander

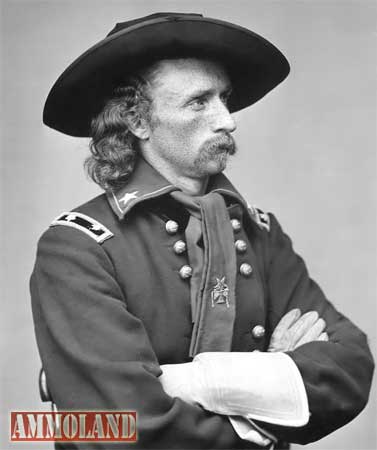

“I am not impetuous or impulsive. I resent that. Everything that I have ever done has been the result of the study that I have made of imaginary military situations that might arise. When I became engaged in campaign or battle and a great emergency arose, everything that I had ever read or studied focused in my mind as if the situation were under a magnifying glass and my decision was the instantaneous result. My mind worked instantaneously, but always as the result of everything I have ever studied being brought to bear on the situation.” -George Armstrong Custer

Rock Island, IL –-(Ammoland.com)- Few names are as known in American History for their failures as George Armstrong Custer.

Many early Americans have cemented their names into history for their daring-do, ingenuity, talent, inventions, selflessness, or sheer bravery.

Instead, Custer is known for his disappointments, inglorious end, and little else, but is that a fair estimation?

Countless volumes of literature have documented and/or speculated about the man, so to try and author an article with any sort of new material would be folly. However, one can look past the decades of myth and into the documented realities that surrounded his life and death to draw some conclusions that take a step away from the generally accepted notions and wild rumors about Custer and his life.

This article will look at some of those facts that surround Custer’s life and, more specifically, his death. The topic of George Custer is specifically raised because Rock Island Auction Company will bring to the auctioneer’s block an extensively documented elk skin jacket attributed as the Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer’s Death Coat. It is accompanied by a buckskin shirt which is attributed to Lakota Tribe Chief Ran-In-The Face.

Early Life

Born in Ohio on December 5, 1839 to German immigrants from Rhineland, the son of a farmer and blacksmith, George Custer would spend most of his childhood growing up with his half-sister in Monroe, Michigan. Later attending college, in Hopedale Normal College in Hopedale, Ohio, Custer would pay for his own room and board by carrying coal. Custer, known as “Autie” to his immediate family thanks to his early attempts to say his own middle name, would soon have a teaching certificate and teach grammar. However, teaching did not suit George and he would enroll at the U.S. Military Academy in 1857, which also barely fit the man. Custer was a poor student, known for playing pranks on his fellow cadets, earning demerits (726 by one report!), facing near expulsion every term for his exploits, and for famously finishing last in his West Point class of 34.

Many associate this with Custer being “stupid” or unable to absorb military tactics. On the contrary, Custer’s antics always required that he buckle down, adhere to discipline, and work his way back into good graces. Much like later on in life, he showed examples of risk taking, fun seeking, being slightly chaotic, and a strong desire to stand out. His West Point class would graduate a year early due to the demand for officers required by the Civil War. Were it not for that great conflict, many say that Custer’s performance at academy would have earned him an obscure, low ranking post and a short career. In fact, several days after that graduation he “failed in his duty as an officer of the guard” to break up a fight between two cadets. He was court-martialed, but again benefited by the outbreak of the Civil War.

Military Career

Instead of the inglorious posting he had earned, Custer was commissioned a second lieutenant in the 2nd U.S. Cavalry and would bounce around the Union forces through various successes, campaigns, and promotions. In 1862, Custer would come under the command of Maj. Gen. Alfred Peasonton who would introduce Custer to his love of fine, fancy uniforms and political maneuvering.

This would alienate him from some of his men, but he would win over the majority by always being willing to lead attacks, fighting in the front lines, and seldom asking a subordinate to do what he would not do himself.

That same year, Custer would be “introduced” to a young woman he had first seen at age 10, Elizabeth “Libby” Clift Bacon. The young, intelligent beauty was the daughter of a wealthy and powerful judge who disapproved of the budding romance so much that he allegedly refused Custer to enter the house let alone bless the proposal of marriage he offered in November 1862.

Libby was also initially less than impressed with this son of a blacksmith, but George would win her over with persistence. Just prior to the Battle of Gettysburg in June 1863, Custer was promoted from Captain to Brigadier General of Volunteers, forcing Judge Daniel Bacon to relent and allow the courtship.

The two would eventually marry in February of 1864, fourteen months after they met, but would have their honeymoon cut short when he was recalled to active duty. She would return with him to the front, staying in a tent or house near to where the fighting would occur. Libbie would often accompany Custer and the two were nearly inseparable. When they were apart they would write frequently to each other, filling their letters with innuendos, playful language, and sweeping romantic declarations.

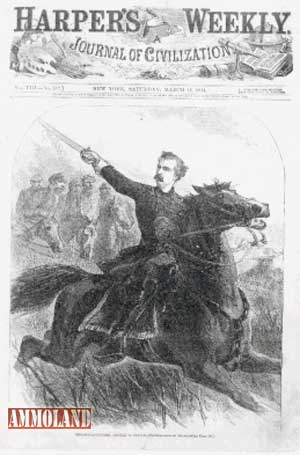

His promotions were well-earned, having performed nobly in many Civil War battles, while his bravado, fancy uniforms, and battlefield victories would make him the darling of the national media. His promotion to Brigadier General make him one of the youngest generals in the union Army at a surprising 23 years of age, earning him the nickname, “Boy General.” He would fight against Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart at Hanover and Hunterstown en route to Gettysburg, where he would have some of his greatest accomplishments.

There are several reported instances reporting that Custer had his horse shot out from under him at more than one time (one source reports 11 times!), would commandeer another horse, and continue to fight in the front with his men. He most famous accomplishment came on July 3rd, 1863 in a feat that this brief synopsis will do little justice. J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry, known as the legendary gray horsemen, “the Invincibles,” was about to overrun the Union’s right flank on the final day of this momentous battle. George Custer mounted a daring counter-charge with a shout to his First Michigan Cavalry, “Come on, you wolverines!” His uniform flashing, red neckerchief snapping in the wind, golden hair straight out behind him, Custer led his forces into a full speed charge. One veteran wrote the following about the collision of the two forces,

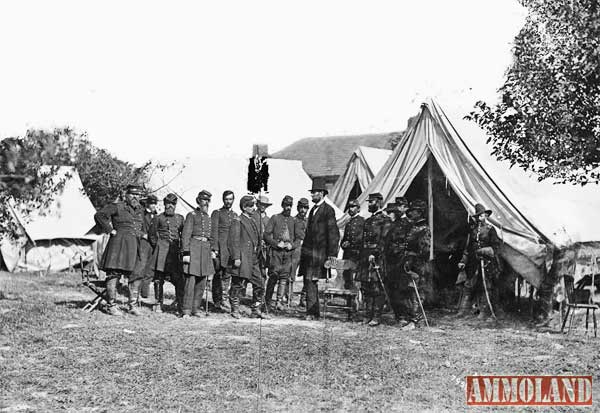

“So sudden and violent was the collision, that many of the horses were turned end over end and crushed their riders beneath them. The clashing of sabers, the firing of pistols, the demands for surrender, and cries of combatants filled the air.” Horses screamed as they slammed into one another. Echoes of gunfire incessantly clapped their deadly applause. Thick smoke and dust choked the combatants, but when it all cleared the Union had repelled the Confederate advance at a critical moment in one of the Civil War’s most important battles. After that day, he became one of the most famous Union officers of the war. He would enjoy other victories, but would also be known for pursuing Robert E. Lee, cutting off Lee’s escape from Appomattox Court House, having his men be the first to receive a flag of truce from the Confederates. Custer himself was present at Lee’s surrender and was given the table on which it was signed for his gallantry. Lt. Gen. Philip Sheridan, in addition to the table, also penned a note to Libbie which reads, “…permit me to say, Madam, that there is scarcely an individual in our service who has contributed more to bring about this desirable result than your gallant husband.”

The nicknames that Custer earned during the Civil War are another testament to the duality of the man. He was called “Iron Butt” and “Hard Ass” for his longevity in the saddle as well as the less flattering “Ringlets” – a jab at his vanity and appearance and a specific reference to his long, curly blond hair.

Indian Battles

After the Civil War, Custer found himself fighting American Indians. However, in a mismanaged campaign the time away from his beloved Libby was too much and he ordered his men on a 150-mile, 55 hour march to Fort Riley where she was located. Some men & horses couldn’t keep up due to the fatigue and were left behind – at least one would be killed by Indians.

It earned him a court-martial and he was suspended from duty for a year. Other sources indicate that his court-martial was also in part due to Custer’s order to shoot deserters and refuse them medical treatment. His reinstatement by friend and admirer Sheridan in 1868 would reinvigorate Custer’s Indian fighting ways.

Much like his days at West Point, he would now have to buckle down to win back his reputation and his good graces.

Buckle down he would. Custer would command the 7th Cavalry with great efficiency, especially at the Battle of Washita River – a one-sided rout on the encampment of Black Kettle and his group of Cheyenne on November 27, 1868. In most accounts of Custer’s life, there is a 5 year gap until it is reported that in 1873, he is sent to Dakota Territory to protect railroad surveyors from the Lakota, but in 1874 he leads an expedition into the Black Hills where, of course, gold is discovered and announced. A gold rush was on in the Black Hills, but the land was promised to the Lakota by the U.S. government only six years prior. The Army was dispatched to protect the new flood of prospectors and to force the Sioux onto reservations. Due to some politics at the time involving President Grant, Gen. John Gibbon, and Gen. George Crook, Custer was almost not allowed to go! Long story short, he was still placed in command after Grant faced strong popular opinions contrary to his own. Custer would go West to meet his demise.

Controversies

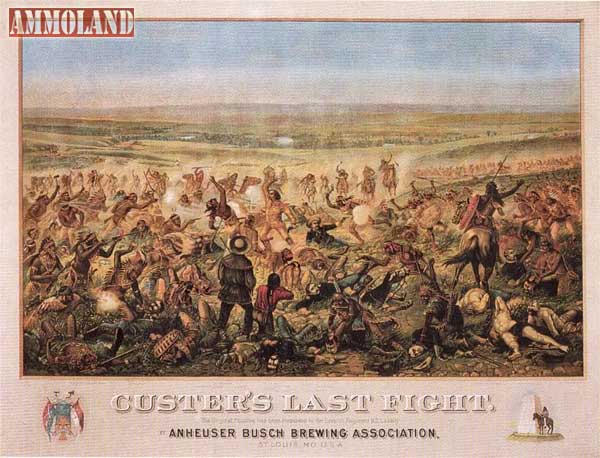

The Battle of Little Big Horn is one of the most examined, studied, and argued about battles in all of U.S. history. The controversies are almost as numerous as the buffalo herds of Custer’s day: when it started, how long it lasted, how Custer was killed, how big the American Indian encampment was, did Custer disobey orders, did Custer ignore the reconnaissance from his scouts, did Custer use bad or faulty tactics, did Sitting Bull ambush Custer’s prong of the attack on the village, did Custer actually die in the river, was there even really a ‘Last Stand,’ how many men died in Deep Ravine, what kind of rifle did the Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho have, could reinforcements have arrived in time, and so on and so forth. Some of these questions can already be answered by conclusive evidence. Some will never be. Some are half-way answered by first-hand accounts given by American Indians after the battle. Oral histories can be inaccurate because the human memory functions more like a story-teller and less like an archive: achievements are aggrandized, language barriers arise, and memories fade.

Many people also question Custer, saying that his reckless behavior, refusal to wait for reinforcements, division of his troops, lack of preparedness (having refused Gatling guns & extra troops, and electing to leave their sabers behind), doomed his cavalry. Undoubtedly, Custer made tactical mistakes in his attack on the village. He underestimated his opponent, came ill-equipped, and was more concerned with Indians escaping (as he had experienced many times before) than with their ability to defend themselves. Not all Custer’s men died that day. Certainly the 210 men in his Battalion (C, E, F, I, & L companies) were killed with the exception of his bugler whom he sent to run a message, but the 7 other companies under Capt. Benteen and Maj. Reno retreated with the majority of their forces still intact.

His legacy after his death was mixed, but would ultimately be decided by his ever-faithful Libby, who would live another 57 years after his death. Custer initially took heavy criticism after his death from a number of important sources like President Grant and his old friend Gen. Philip Sheridan. However Libby campaigned tirelessly for her husband’s reputation as a gallant, fearless, dedicated man. She would write articles, give speeches, travel extensively, and author several books to supplement her income and save her husband’s name. It worked. Custer was long revered as an American martyr in the same vein as the Alamo. The immediate set-up of this image would allow the American people to seek vengeance on the American Indians who had slaughtered their national hero just before the nation’s Centennial Celebration. Crazy Horse surrendered 11 months later was killed 3 months after that when he was supposedly bayoneted during an escape attempt.

The Little Big Horn was the end of the Oglala Lakota as well.

The Coat

Lot 3310: Historic Indian Wars Period Jacket and Shirt Attributed to General Custer the Famous Battle of Little Bighorn with Documentation

To the untrained observer the coat might look like just another coat. It is tattered, stiff with age, and blood stained. However, this elk skin jacket was once quite the luxurious garment. It has been embroidered, fringed, patterned with triangles and flowers, decorated with silk, and a several different (then) exotic materials. Both the Smithsonian Museum and the William “Buffalo Bill” Cody have tried to unsuccessfully purchase the coat, but not for its adornments. The coat has ties to the Battle of Little Big Horn and even to Lt. Col. George A. Custer himself!

The coat’s history is told to us by John. A. Dietzen, the man whose father originally procured the coat. He writes in a 1958 letter to eventual owner Col. Raymond C. Vietzen,

“…my father brought the coat back from the West when he returned in 1880. He told my mother, and the story was repeated to me in later years, that he had won the coat in a shooting match from a friendly Indian. The Indian was one of those employed by the U.S. Army for Scout work. He was one of the group who trapped and killed Sitting Bull following the death of General Custer. He told my father that the coat had been taken by Sitting Bull from General Custer who was wearing it at the time he was killed… It is impossible to establish an authentic history of the coat. I have only the above family history and my father’s army discharge papers which definitely place him in service at the time of General Custer’s death.”

Part of the extensive documentation of this jacket includes the discharge papers of Joseph Dietzen that confirm he was in the service at the time of Custer’s death. The coat has two bullet holes, in the back and in the sleeve, with blood stains still visible. The fringe shows saddle wear on the rear. The Smithsonian felt that the floral designs on the coat represented several American Indian tribes and that the coat was “made especially for a white chief by the Indians.” The jacket was in the Dietzen family until 1959 when it was sold to Col. Raymond Vietzen who owned the Indian Ridge Museum in Elyria, Ohio. When the colonel died, the jacket and the rest of the museum collection was sold at auction.

The debate of authenticity is most succinctly laid out in the item’s official auction description, which will be partially reprinted here.

“Custer was known for wearing a buckskin coat and trousers while serving out West. He owned several. In 1912, Custer’s widow donated one of her late husband’s buckskin jackets to the Smithsonian Institution where the jacket remains today. But did Custer wear a buckskin jacket on the day he died?

Many accounts by Indian warriors who fought at the Little Bighorn told of a death of a buckskin clad officer. Many assumed that this officer was Custer, but other officers of the regiment also wore buckskins, including Custer’s brother whose mutilated body was stripped of his jacket. White Bull, the nephew of Siting Bull and one of several men who claimed credit for killing Custer, attested that he shot a buckskin clad officer riding “a fine looking big horse, a sorrel with a blazed face and four white stockings.” Custer was the only officer on a sorrel horse with four white socks and this one detail does suggest that Custer died wearing a buckskin jacket, however, the historical record is not completely kind to the image of Custer valiantly fighting off Indians in his buckskin jacket as popularized in paintings, books, and nearly 50 movies which retell the tale of Custer’s Last Stand.

In 1896, former Seventh Cavalry Captain Edward S. Godfrey is on record stating, “The day was warm and few had on any kind of blouse.” Here, blouse is a Victorian-era term for a coat. (It is of interest that Edward S. Godfrey recalled finding 1st Lt. James Parter’s buckskin blouse in a deserted Indian village several days after the battle. He stated that “from the shot holes in it [Porter] must have had it on and must have been shot from the rear, left side, the bullet coming out on the left breast near the heart.”) Testifying at the Reno Court of Inquiry, Trumpeter Giovanni Martini (John Martin), the only survivor from Custer’s company in the Battle of Little Bighorn, stated that Custer had taken off his jacket and tied it to his saddle pack. Custer was seen wearing a privately made blue double breasted bib trimmed in yellow cloth tape with crossed sabers and a “7” embroidered on the points of the collar, a style of shirt that most of the officers of the regiment wore. Martini’s description of Custer’s appearance is verified by Peter Thompson, a Scots-American soldier who was awarded a Medal of Honor for his actions at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. In Thompson’s own words, “Custer was mounted on his sorrel horse and it being a very hot day he was in his shirt sleeves; his buckskin pants tucked into his boots; his buckskin shirt fastened to the rear of his saddle; and a broad brimmed cream colored hat on his head, the brim of which was turned up on the right side and fastened by a small hook and eye to its crown…This was the appearance of Custer on the day that he entered his last battle, and just one half hour before the fight commenced between him and the Sioux.” Lt. Charles A. DeRudio also attested that Custer was in a blue shirt and buckskin pants. Custer documentarian and film historian Dan Gagliasso has concluded, “The flamboyant former Civil War Hero [Custer] certainly had a buckskin jacket with him that day, as did at least seven other officers who died with his five companies of cavalry on the Creasy Grass Ridge, including his brother Captain Tom Custer, Captain Myles Keogh, commander of I Company, and the regimental adjutant First Lieutenant W.W. Cooke…[But when considering the eyewitness testimony] it now becomes quite doubtful that Custer was the buckskin clad officer shot at the river ford that day” (see, the article Strange Hats and Buckskin Coats in the magazine True West, May/June 2001, Vol. 48, Issue 4). One must draw their own conclusion regarding the history of this jacket based on the documentation! With the exception of his socks and the shoe portion of one boot, Custer’s body was stripped naked. The Colonel’s body was found among a group of about 42 dead men, possibly in a defensive posture. He had a bullet wound in the temple and left side, and compared to the bodies of his comrades, had been mildly mutilated.”

This lot also includes a second item attributed to the Indian Wars, a deer skin shirt. It is much simpler than the elaborate elk sin coat, but the consignor notes attribute this shirt as the personal property of Rain-In-The-Face, however there is currently no documentation possessed by Rock Island Auction Company that will authenticate this claim. Rain-In-The-Face was among the warriors present at Little Big Horn and at one time was one of several individuals claiming to have killed Custer, though he took it a step further and also claimed to have cut out the heart of Thomas Custer as immortalized in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem “The Revenge of Rain-In-The-Face.” However, immediately before his death Rain-In-The-Face would recant both of these claims.

There you have it! A flashy man and an equally flashy coat – the mention of either is sure to spark much conversation. Fully aware of this, Rock Island Auction Company’s Executive Director of Operations, Laurence Thomson, says, “While the documentation accompanying the jacket is not a slam dunk, it certainly presents a compelling case. I can’t tell you how many times in this business we are approached by individuals who claim to own Ben Franklin’s bifocals, Abraham Lincoln’s axe, or General Robert E. Lee’s sword. Rarely do the items even look the part let alone have any documentation or provenance to back up their claim. This jacket is not only of the period and style but is accompanied by enough evidence to certainly be plausible. Items from the Battle of the Little Bighorn have sold for millions at public auction. Since we cannot say for certain, we want to simply present the facts, and the let buyers make up their own mind.”

SOURCES:

- https://www.historynet.com/george-custer

- https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/transcript/custer-transcript/?flavour=mobile

- https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history-archaeology/How-the-Battle-of-Little-Bighorn-Was-Won.html

- https://www.usnews.com/usnews/doubleissue/mysteries/custer.htm

About:

Rock Island Auction Company has been solely owned and operated by Patrick Hogan. This company was conceived on the idea that both the sellers and buyers should be completely informed and provided a professional venue for a true auction. After working with two other auction companies, Mr. Hogan began Rock Island Auction in 1993. Rock Island Auction Company has grown to be one of the top firearms auction houses in the nation. Under Mr. Hogan’s guidance the company has experienced growth each and every year; and he is the first to say it is his staff’s hard work and determination that have yielded such results. Visit: www.rockislandauction.com