Fungus And The Future Of Bats

Fungi have a history of assaulting North America’s outdoors.

By Joe Kosack

Wildlife Conservation Education Specialist

Pennsylvania Game Commission

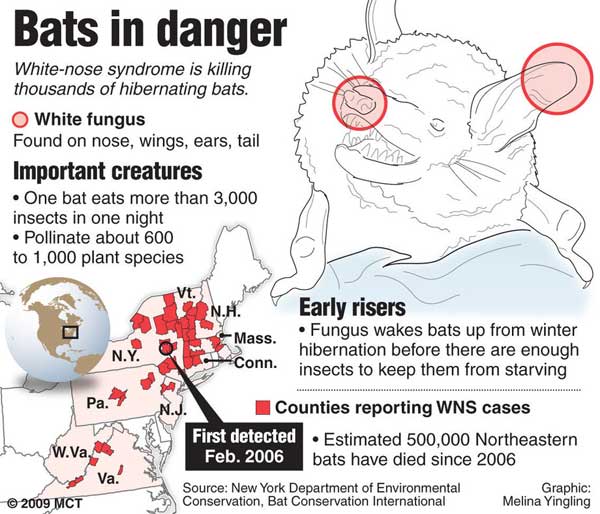

HARRISBURG, PA –-(Ammoland.com)- Cave bats have long been some of North America’s most successful species. Then, in 2006, White-Nosed Syndrome (WNS) surfaced in Howe’s Cave near Albany, New York, and the future of North America’s cave bats soon became anything but certain.

The disease has since spread north into Canada, south to North Carolina and west to Oklahoma. This month, bats will be returning to their hibernation quarters in mines and caves and their seasonal battle for survival will resume. WNS strikes bats as they overwinter underground.

More than a million cave bats have died from the fungus Geomyces destructans (Gd) that causes WNS over the past five years. The pervasive Gd strikes while bats are in communal hibernation, often clustered like sardines in a tin to conserve energy. When this fungus invades hibernacula, it has been profoundly damaging to cave bats, which, in Pennsylvania, includes the little brown bat, big brown bat, eastern pipistrelle, Indiana bat, small-footed bat and northern long-eared bat.

Gd is a cold-loving fungus that thrives on the bodies of hibernating bats in caves and mines. Once it appears in these subterranean areas, it stays. That’s bad news for the bats that hibernate in these chambers. The very caves and mines that for centuries sheltered bats from the elements and pestilence now harbor the world’s preeminent cave bat-killing pathogen, Gd.

“If you were pondering a perfect storm on cave bats, the nastiest catalysts would be organisms that could exist and strike in the dark, cold and wet environments where bats hibernate,” explained Greg Turner, Game Commission biologist. “Their vulnerability then is unparalleled, because their immune system is shut down to conserve energy. Geomyces destrutans has found this opening. Now it’s up to bats to find a defense.”

In Pennsylvania, bats spend six months annually in hibernation, riding out winter and living off a finite supply of energy generated from consuming massive quantities of flying insects. Gd irritates the deep-sleeping bats, forcing them out of their hibernation stupor, which requires increased energy consumption from a reserve that barely sustains them through winter. Death often follows, regardless of whether the bat stays put or flies out over the winter landscape looking for food that isn’t there.

Although some hibernacula have been scorched by Gd and remain absent of all bat life, there have been some survivors and residents at some contaminated caves and mines in Pennsylvania and New York for several years. It’s a finding that gives hope; a potential sign of resistance. But it’s also early in this fungal invasion, so observations are simply that, something noted, something more to be monitored.

Prior to the Gd outbreak, North America’s two most notable wildlife-related fungal invasions were the ongoing American chestnut blight and amphibian population decline, which is caused by Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd), and commonly called Chytrid fungus. Neither of these crippling fungi, nor Gd, belongs in North America. They all found their way here over the past century hitchhiking either on products or people. And, unfortunately, they’re here to stay.

The chestnut blight, caused by the fungus Cryphonectria parasitica, was first noted at the Bronx Zoo in 1904. It is believed to have sprung from a shipment of Asian chestnut trees. At the time, American chestnut trees – attaining heights up to 100 feet – dominated forests, particularly in the Appalachians, from Massachusetts to Alabama. The blight was in Pennsylvania by 1911, when the state created the Commission for the Investigation and Control of the Chestnut Tree Blight Disease in Pennsylvania. By the start of World War II, American chestnuts were mostly gone from eastern forests. What remained were stunted remnants of a species that once was as plentiful in Pennsylvania as oaks are today.

What’s interesting about the chestnut blight is that it didn’t chase the American chestnut into extinction. Rather, it crippled the species, essentially preventing it from maturing through infestations that kill every part of a chestnut tree above the initial area of infection. Root systems of American chestnuts continue to push new growth in our forests only to be snuffed out by the blight, which remains in many areas and is spread by precipitation, flooding and wildlife. There also are some resilient native American chestnut trees that have survived the blight.

The bad news about exotic wildlife pathogens is that when they emerge they rarely can be extricated. Once the chestnut blight got to North America, it made itself right at home. Still, the blight couldn’t snuff out the American chestnut completely, which holds promise.

“Where there’s life, there is hope,” noted Dave Gustafson, Game Commission Forestry Division chief. “To this day, work continues, particularly by The American Chestnut Foundation, to perfect a blight-resistant tree – crossbred from the few still standing indigenous trees – that will augment and hopefully restore the American chestnut’s presence in the eastern United States. It’s an attempt to accelerate nature’s immunity-building process. For the American chestnut’s sake, and the benefit of wildlife, let’s hope it works. Otherwise it could take centuries for the American chestnut to build immunity and reclaim its once commanding presence in our forests.”

To date, even in New York, Gd has not eliminated cave bats in some their historic hibernacula. Some bats hang on, just like the American chestnut. The same is true for some amphibians facing Bd. Also a fungal pathogen, Bd has been implicated in the declines and extinctions of certain species of amphibians in cooler or higher elevation areas of Australia, Costa Rica, Brazil, the United States and many other counties over the past couple decades. Most vulnerable are those species that have little ability to adapt to changing conditions and are found over smaller geographic ranges that harbor ideal conditions for Bd.

Bd has been found in red-spotted newts and green frogs at several sites in northwestern Pennsylvania, including on the Game Commission’s State Game Lands 69 and 277 in Crawford County. The research findings were published in 2010 in the Herpetological Review. The work was performed by Maya L. Groner and Rick A. Relyea through the University of Pittsburgh.

Researchers have been studying Bd – first identified in 1993 – for some time now, and have shed some light on how the fungus fuels the disease Chytridiomycosis, which is what kills amphibians. Some amphibians are resistant to Bd. It spreads through zoospores that disperse in water, but also can hitchhike on amphibians sold in the pet trade. It is believed by many to have originated in Africa.

Bd seems to be less debilitating to hosts when temperatures are above 80 degrees Fahrenheit. Hosts harboring the affliction in hotter climes don’t seem to be dying from it, while their same-species counterparts at cooler, higher elevations are. Similar evidence is emerging in field research of bat populations contracting WNS in states south of Pennsylvania and in Europe. Maybe it’s possible that some bat populations – or possibly their hibernacula – are more resistant. Gd thrives in temperatures under 70 degrees Fahrenheit.

The European strain of Geomyces destructans has been confirmed in eight species of cave bats. But the mortality rates of bats with Gd in Europe are almost inconsequential; less than two percent were dying, according to recent research. It is hypothesized Gd has been in Europe for thousands of years, and bats there have developed an immunity to it over time.

The situation, however, is different on our side of the Atlantic, where Gd is unchallenged and has been increasing its range in leaps and bounds.

Five years of following WNS has helped wildlife managers identify and better understand what Gd is and what potential limitations it may have. The future for North American bats seems to be brighter as a result of this important work and the track record of other foreign fungi that have invaded our outdoors. It is a perception bolstered by our increased understanding of Gd and the sometimes surprising resiliency of nature, even when natural order has been disrupted by unnatural events. Remember how bad things were for bald eagles and American bison?

That some amphibians are immune to Bd and others can mount a defense to it in warmer climates suggests its pathogenicity may not be as crushing as presumed when it first was identified. Field research now seems to be showing some signs that Gd also may not be the inescapable epidemiological juggernaut it was first expected to be. Ultimately, time and the bats will sort out whether bats persevere. But, the battle North American bats must fight with Gd still is likely closer to its beginning than its end.

“As the populations of affected bat species decline, the distribution of survivors will likely shrink to core populations and habitats, creating new management challenges in identification, protection and potential recovery of survivors and habitats,” noted Cal Butchkoski, Game Commission biologist. “For our bats, since no treatments are on the horizon, we must fall back to conservative management. As colonies decline, no number will be too small to protect and manage.”

Fungal outbreaks in our ever-increasing global society clearly lay bare the harm associated with releasing or transporting – whether intentionally or unintentionally – invasive species. It is why all Pennsylvanians must be vigilant about organisms hitchhiking on their equipment and gear and illegal releases of invasive species. Much good can come from our increased concern and attention.