Tom explains the purpose and use of the first and second focal plane in modern rifle scopes.

USA –-(Ammoland.com)- When you hear terminology like “focal plane” it sounds like serious physics is about come at you like an amped up spider monkey, but it’s actually a pretty simple concept. Here’s why. The reticle that you see through a scope is a physical thing. Back in the day, reticles were made from actual Wooly Mammoth hairs Crazy Glued onto the glass lenses. In more modern scopes, the reticle is usually a pattern etched onto glass. The important thing is that’s the reticle is a “physical” object, so it has to be placed somewhere in the scope tube.

That’s where first and second focal planes come into play.

In a first focal plane scope, the reticle is placed in front of the magnification lenses. Think about this for a second. Just like the target and anything else you look at, whatever is in front of the magnification lenses is going to get… magnified. That means that the reticle itself will grow and shrink in size if you change the magnification on a variable power scope. Of course, on a fixed [read non-adjustable] magnification scope, the reticle will always look the same, even if it’s in the first focal plane, because there’s no magnification setting to change. Generally speaking, first focal plane scopes are more of a pain to manufacture, so you’ll often seem them priced higher than a second focal plane scope with comparable features. However, technology benefits march on and over the past couple of years, first focal plane scopes have become much more affordable.

With a second focal plane scope, the reticle is located behind the magnification lens, or closer to your eyeball. Since whatever the scope is viewing has already been magnified, the reticle appearance won’t change as you adjust magnification power up and down. The reticle appears the same at any power setting.

So, that’s all there is to first and second focal plane scopes. The important things to know are the ramifications of reticle placement, so let’s get into that next.

Magnification and Reticle Theory

Without getting into obscure mathematical equations that neither you nor I can even begin to understand, think about proportionality concepts. Rules of proportion are a big deal in long-range shooting as it’s the underlying concept that makes things like MOA and Milliradian adjustment and range estimation work.

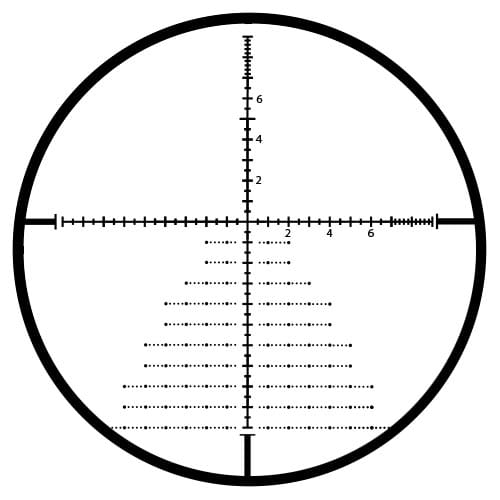

If you’re using a reticle to do things like account for bullet drop or determine the range to a target, it’s important that the relationship between the reticle and the target remain the same. To completely butcher optical science, hash marks in your scope need to represent the same physical distance for something like bullet drop to have predictable and repeatable performance. With a reticle that is “fixed” in size is paired with a change in magnification, one thing (the reticle) remains constant while the other (the target) changes in perceived size. That throws off the predictable relationship between reticle and target.

Holdover Issues Between First and Second Focal Planes

Let’s assume we’re making a long distance shot. To account for bullet drop, we’re using holdover and not adjusting turrets on a scope. Suppose we have to hold at the 10 MOA hashmark below the crosshair intersection. Those ten MOA hashmarks may represent a physical distance at the 500-yard target of 55 inches given the actual trajectory of our example bullet.

With a second focal plane scope, as we increase the power, the relationship between our 10 MOA “view” and the actual amount of height at the target completely changes because the reticle didn’t adjust with the magnification of the target. You see a lot less “height” between within that 10 MOA hashmark range. In a first focal plane scope, since the reticle grows in size proportionally with the target as magnification is increased, that same 10 MOA holdover works at any power level.

Ranging Issues Between First and Second Focal Planes

The same gotcha applies when using a reticle to determine the range of an object with a second focal plane scope. Because you’re “measuring” the size of a distant object using hashmarks on the reticle itself, then changing the magnification changes the apparent size of the object, and your measurement will be skewed. With a first focal plane optic, the reticle and object change in size together as you adjust the magnification power so that you can perform the exact same range calculations at any power level. However, since the reticle will grow as you increase power, you might find it easier to view and measure targets precisely at higher power levels anyway.

So How Do Second Focal Plane Scopes Work?

So, after all this explanation about how holdovers and ranging functions fail when you change magnification, then how do second focal plane scopes work at all? It’s because those functions are calibrated to work at a single magnification level, usually the maximum magnification setting on the optic. So, if you’re using a second focal plane 3-9x or 5-20x scope (or any other), before you use the reticle to adjust for holdover, you’ll need to quickly zoom up the power level to the maximum setting and then get to work.

You can also get into math and perform conversions for holdovers and range calculations at different power levels. Since everything is proportional, it’s not hard. To me, it’s far easier to spin the magnifying ring up and work the scope as designed. Besides, you’ll have a clearer view of the target anyway.

First And Second Focal Plane , Which Reticle to Choose?

The benefits of a second focal plane reticle are that you can have a finer and more precise reticle design that works at any magnification level. The drawbacks are that range estimation and holdover marks are only valid at a designated power setting, usually full magnification. You’ll have to remember to switch to full power before using the reticle for holdover and ranging.

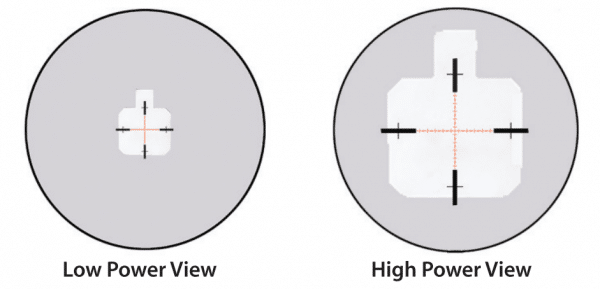

With first focal plane scopes, you’ll only see the full-scale reticle at the highest power level. At lower levels, the crosshairs will probably be visible, but finer hashmarks you might use for holdovers and ranging might be too small to be useful. Some scope makers have turned this into a benefit. As certain reticle designs shrink, they begin to look more like red dot optic since the dense center crosshair area becomes a small solid object. That allows you to use a scope more like a close-range red dot optic at the lower power levels while still having a complex and precise reticle pattern available for longer range work. This approach is especially effective with illuminated reticles.

As with most things, there is no right or wrong when it comes to first and second focal plane ; the choice is a matter of personal preference. Next time your shopping for optics, pick up similar scopes of each style and see how the reticles appear at different power levels to figure out what best matches your style and preference. Did I mention there are dual focal plane scopes on the horizon, that is a whole other article.

About Tom McHale

Tom McHale is the author of the Practical Guides book series that guides new and experienced shooters alike in a fun, approachable, and practical way. His books are available in print and eBook format on Amazon. You can also find him on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest.