Arizona – -(Ammoland.com)- The ubiquity of inexpensive and capable video and audio recording devises is changing the legal and political landscape for everyone, but especially for police, criminals, and armed Americans.

The open carry movement learned early on that recording of an incident removed the he said/she said ambiguity that is often found to be in a police officer’s favor. There have been many cases where the interaction was recorded and a settlement was paid to the person exercising their rights.

Many defensive actions by armed Americans have been caught on surveillance cameras and have gone viral on the Internet.

Recent gun store robbery and gunfight caught on video.

The trend in the courts is to find that recording in public is a first amendment right; specifically the recording of public officials, including police, in the performance of their public duties. In 2011 the First Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that way. From dmlp.org:

The CMLP is thrilled to report that in the case of Glik v. Cunniffe, which the CMLP has blogged previously and in which the CMLP attempted to file an amicus brief, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit has issued a resounding and unanimous opinion in support of the First Amendment right to record the actions of police in public.

The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals ruled the same way in striking down an Illinois law in 2012. The law specifically made it illegal to record police officers. That law was appealed to the Supreme court, and the Supreme court decided not to hear the case. From chicagotribune.com:

Writing for the 7th Circuit majority, Judge Diane Sykes said Alvarez staked out an “extreme position” in arguing that openly recording what police say on the job on streets, sidewalks, plazas and parks deserved no First Amendment protection.

Judge Richard Posner dissented, saying the ruling “casts a shadow” over electronic privacy statutes nationwide that require consent of at least one party to record many conversations.

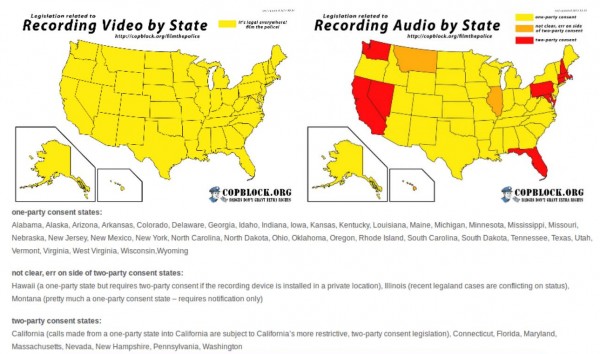

In the map shown above, the laws are generally crafted as “wiretap” laws designed to restrict the recording of telephone conversations. That is far different than recording public interactions, in which there is little expectation of privacy. I am unaware of any other appeals court cases that address the issue. As nearly half of the people in the small number of states with restrictive laws reside in the Ninth Circuit, and with California having one of the most restrictive laws, a challenge of the California law and to the Ninth Circuit seems likely at some point.

A retired state patrol officer has told me that he expects that all police will record all of their time on duty within 10 years. President Obama has pushed for certain police agencies to require the use of body cameras while on duty.

For armed Americans, a recorder has become as much of a tool for defending Constitutional rights as a firearm.

There may come a time when the first question a prosecutor asks is “Where is the recording?“.

c2014 by Dean Weingarten: Permission to share is granted when this notice is included. Link to Gun Watch

About Dean Weingarten;

Dean Weingarten has been a peace officer, a military officer, was on the University of Wisconsin Pistol Team for four years, and was first certified to teach firearms safety in 1973. He taught the Arizona concealed carry course for fifteen years until the goal of constitutional carry was attained. He has degrees in meteorology and mining engineering, and recently retired from the Department of Defense after a 30 year career in Army Research, Development, Testing, and Evaluation.