This week’s Law of Self Defense: Question of the Week comes from William Strunk, Jr. (@cdrusnret), who asked:

USA – -(Ammoland.com)- This being the law, the answer is naturally both “yes” and “no”. So, let’s step through the analysis.

Classic Self-Defense: Illegal Weapon Should Not Matter

From a classical self-defense perspective, whether the weapon used in self-defense is lawfully possessed doesn’t really matter. The five core elements of self-defense – innocence, imminence, proportionality, avoidance, and reasonableness – don’t make any reference whatever to the legality or illegality of one’s defensive weapon.

Entire Claim of Self-Defense Can Hinge on Defendant’s Credibility

Nevertheless, the use of an unlawfully carried weapon in self-defense -indeed, the mere unlawful possession of the weapon can have profoundly negative effects on your self-defense claim under certain circumstances.

It is not at all uncommon in self-defense cases that the defendant’s own testimony – whether on the 911 call immediately after the defensive use of force, or statements made to police investigating the event, testimony offered pre-trial for a self-defense immunity hearing, or testimony offered at the trial itself – is the main or even only source of evidence supporting a claim of self-defense.

If the only evidence of self-defense comes from the defendant’s own testimony, it is obviously essential that the defendant be perceived as possessing the utmost credibility. After the all, the defendant’s testimony is generally only as believable as the defendant himself.

As a defense attorney, I want my client to look as white as the driven snow if there is any chance I will use his testimony to support his claim of self-defense, and particularly if I’m compelled to put him on the witness stand and subject him to cross-examination.

Getting a felony conviction for the illegal possession of a gun is not going to help the defendant’s testimony in front of the jury. Further, a felony conviction feeds in nicely to the prosecution’s compelling narrative of guilt, that the defendant is a bad guy who does bad things—including shooting people NOT in self-defense.

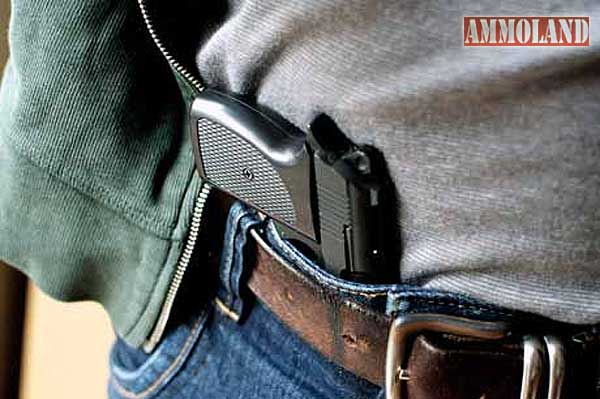

This is especially for any of the jurors who are not particularly comfortable around firearms, especially handguns – a sentiment that is far more common than those of us who live deeply immersed in the gun community might recognize. Even the licensed carry of a pistol is looked at askance by many people, and the prosecution is sure to trot out the old argument that “the defendant is just a nut with a gun looking to shoot someone” – but at least licensed carry is lawful, and something done by law abiding people.

The illegal carry of a gun, on the other hands, is something done by bad guys. And you don’t want to look like a bad guy in a self-defense case, because the connotation goes right to the element of innocence. If you’re perceived as the bad guy, is it more or less likely the jury will believe the prosecution’s arguments that you were the aggressor, or at the very least were a willing participant in mutual combat?

If the prosecution can sell the jury on either of these notions – poof! There goes your self-defense claim. The aggressor or mutual combatant is not entitled to justify their use of force against another as self-defense.

Illegal Carry Can Also Strip You of Stand-Your-Ground

Many prosecutors hate Stand-Your-Ground laws because it takes away one of their most potent weapons against a self-defense claim. Without Stand-Your-Ground the prosecution can argue that the defender had a legal duty to take advantage of any safe avenue of retreat before he could lawfully resort to deadly force in self-defense.

Keep in mind, of course, that the jury wasn’t at the defensive gun use scene. All they know is the stories they are being told in court, the narrative of compelling guilt by the State and the narrative of compelling innocence by the defense.

If the State chooses to attack your claim of self-defense on the issue of avoidance/retreat, and has a way to get around Stand-Your-Ground, the prosecutor can simply role in a huge drawing of the scene on a big easel. And on that drawing he will have highlighted the dozen or so safe avenues of retreat that you could have taken instead of shooting and killing the “victim” (e.g., the person who attacked you).

Of course, what may look like an obviously safe avenue of retreat using perfect hindsight and from the security of a guarded court room may not have been at all obvious to you, the defender, engaged in an existential fight for your life against a vicious attacker. There’s no way, however, to truly immerse the jury in that existential experience. The “retreat drawing,” however, is simple.

It was precisely because of such “safe retreat” arguments by prosecutors that State legislatures all around the country began adopting Stand-Your-Ground laws to reverse the duty-to-retreat they had adopted in earlier decades.

(Of course, roughly half of today’s Stand-Your-Ground states never adopted any such duty-to-retreat policy, and had no need to adopt Stand-Your-Ground statutes.)

Stand-Your-Ground is thus properly understood as a policy statement by the legislature to prosecutors that if they have a defendant who did everything correctly in acting in self-defense—they were the innocent party, the threat they faced was imminent, they used no more force than necessary, and their perceptions and conduct were both subjectively and objectively reasonable—that the prosecutors were not going to be permitted to put such a defendant in jail for the rest of their lives simply because in the heat of a fight for survival they failed to notice a safe avenue of retreat.

Stand-Your-Ground: “Only ‘Good Guys’ Need Apply”

Stand-Your-Ground, then, has always been intended to apply to good guys otherwise acting in lawful self-defense, not to bad guys. The innocence element that must still be met ought to take care of this concern. But some states have felt that something more was required to ensure that bad guys could not take advantage of Stand-Your-Ground.

These states therefore embed in Stand-Your-Ground not merely that the defender must have been in a place he had a right to be – you can’t have been trespassing or breaking into someone’s home, for example – but you must also not have been engaged in any illegal activity. This latter clause is generally understood to be intended to apply to drug dealers and similar folks.

States that include this “no illegal activity” language in their Stand-Your-Ground laws include (but are not limited to):

- Alabama: 13A-3-23 Use of force in defense of a person.

- Florida: 776.013 Home protection; use of deadly force; presumption of fear of death or great bodily harm.

- Kansas: 21-5230. Use of force; no duty to retreat.

- Kentucky: 503.055 Use of defensive force regarding dwelling, residence, or occupied vehicle — Exceptions.

- Louisiana: §19. Use of force or violence in defense

- Mississippi: § 97-3-15. Homicide; justifiable homicide; use of defensive force; duty to retreat.

- Nevada: 200.120 “Justifiable homicide” defined; no duty to retreat under certain circumstances.

- Oklahoma: 21-1289.25 Physical or deadly force against intruder.

- Pennsylvania: § 505. Use of force in self-protection.

- South Carolina: § 16-11-440. Presumption of reasonable fear of imminent peril when using deadly force against another unlawfully entering residence, occupied vehicle or place of business.

- Tennessee: 39-11-611. Self-defense.

- Texas: Sec. 9.31. Self-defense.

- West Virginia: §55-7-22. Civil relief for persons resisting certain criminal activities.

(Note: Many of these states also strip defenders of certain presumptions of reasonable fear and self-defense immunity of the defender was engaged in unlawful activity at the time.)

In the context of this LOSD Question of the Week, then, the illegal carry of a gun can readily qualify as “unlawful activity” sufficient to trigger the statutory exclusion of the benefits of Stand-Your-Ground, and exposing you once again to the “safe avenue of retreat” arguments used with such success by prosecutors to destroy self-defense claims.

Wrap-up

So, those are some of the ways in which the use of an illegally carried gun can negatively affect your claim of having acted in self-defense.

This week’s winner, “William Strunk, Jr. ,” (@cdrusnret) will get their choice of a complimentary autographed copy of “The Law of Self Defense, 2nd Edition” or a snazzy LOSD baseball cap, as soon as they get me their mailing address.

If you’d like to submit your own Question of the Week, and become eligible to win a free book or hat, simply submit your question at Ask Andrew at the Law of Self Defense web site., to my Twitter account at @LawSelfDefense (no “of”).

Stay safe! -Andrew, @LawSelfDefenseAndrew F. Branca is an MA lawyer and the author of the seminal book “The Law of Self Defense, 2nd Edition,” available at the Law of Self Defense blog (where a custom autograph can be specified, great for gift purchases!), Amazon.com (paperback and Kindle), Barnes & Noble (paperback and Nook), and elsewhere.

In addition to the book, Andrew also conducts Law of Self Defense Seminars all around the country. Seminars for 2014 are currently being scheduled, if you’d like to see one held in your area fill out the comment box on the LOSD Seminar review page, where you can also see reviews of recently completed seminars in New Hampshire, Maine, Texas, Massachusetts, Ohio, Virginia, Florida, South Carolina, Georgia, and elsewhere.

Andrew is also a contributing author on self defense law topics to Combat Handguns, Ammoland.com, Legal Insurrection, and others.

You can follow Andrew on Twitter at @LawSelfDefense, on Facebook, and at his blog, The Law of Self Defense