Story by Tori J. McCormick – Photos by Nigel Simms

Bismarck, ND –-(Ammoland.com)- Somewhere south of Morgan City, La., on the fabled Atchafalaya River basin, Jeff Green is navigating his custom-made 30-foot Hanko boat with a sky lounge and 250-horsepower motor as he cuts a wake through an ancient bayou on his way to his family’s half-century-old duck camp.

Greg Green, Jeff’s brother, is along for the nearly hour-long ride, as are childhood friend Mitch McHugh and three guests.

If you cup an ear and listen hard enough, as the haunting cypress swamp blurrily passes by like a cinematic ode to the Blair Witch Project, you can hear the music throbbing through his speakers as the refreshingly cool January air slithers beneath your collar and spirals down your neck like an invisible amusement park ride.

Wish I was back on the Bayou.

Rollin’ with some Cajun Queen.

Wishin’ I were a fast freight train,

Just a chooglin’ on down to New Orleans.

Born On The Bayou;

Born On The Bayou;

Born On The Bayou.

The coolers on board — and there’s more than one — runneth over with oysters and shrimp and crab and bullfrogs and doves and God knows what other exotic wild protein whose every part will be hand-spun into delicacies that will tie your tongue in knots and make your stomach scream for more.

Indeed, for the outsider whose “green” palate isn’t accustomed to the riches of Cajun cuisine (or any other delectable concoction conceived at duck camp), buckle up. Your taste buds are about to be hijacked by a savory, oh-my-God gastronomical wonderland, food as mega-calorie pyrotechnic.

For the record, the duck hunters of South Louisiana, a hard-living, fun-loving, distinctly prideful bunch, love to kill “their ducks” perhaps as much as any waterfowling demographic in North America. But the duck camp experience that defines part of the coastal hunting culture neither begins nor ends with slapping the trigger and watching a green-winged teal, an American wigeon or a drake northern shoveler (affectionately called a flathead mallard in bayou country) tumble from the sky.

Duck hunting is the tie that binds. The experience is the confluence of several cultural happenings, but food doesn’t play second fiddle to any of them.

“This is South Louisiana,” said Greg Green, at the R.J. Marcell Memorial Boat Ramp in Morgan City, minutes before departing downriver to duck camp, “so get ready to have some fun.”

South Louisiana Culture

When Delta Waterfowl Communications Director Nigel Simms and I decided to travel to coastal Louisiana in January to sample the duck camp experience, neither of us knew what to expect. Aside from what I had read and heard over the years, I knew very little about the region’s history or culture. Delta Development Director Bryan King has spent eight years as a regional director in Louisiana, particularly in its southern coastal reaches where people either work on the water, play on the water or both.

“Food is everywhere in South Louisiana because it has been woven into the culture for generations,” he said, noting he nearly put on 20 pounds his first few months on the job before reigning in his eating habits.

“Duck hunters are a big part of it. I personally have never experienced another culture in the United States that celebrates not just what it has harvested in the field, but as importantly, what that harvest will become once it’s in a big black pot and, ultimately, on the plate.”

As King spoke, serving as our defacto tour guide/cultural anthropologist, we sat at the Atchafalaya Café in Morgan City, enjoying — really enjoying — a bowl of seafood etouffee, deep-fried okra and iced tea. And did I mention the po’boy with deep-fried oysters?

A significant portion of South Louisiana — particularly its rural areas — is dominated by Cajuns, descendents of Acadian exiles who first came to the region in the late 18th century from Nova Scotia. However, Cajuns have, over time, absorbed and been influenced by other regional cultures: German, Spanish, Anglo Italian, Native American, Slavanian and more.

“It really is a stew of ethnic diversity, and its shows through in the food and music and in the diversity of language and customs,” King said. “There’s one word to me that defines the lifestyle and culture of south Louisiana: hard. Most of the people I’ve come to know embody the word. They work hard, play hard, cook hard, eat hard, drink hard and hunt hard.”

King had arranged a day of hunting with the Green brothers, both of whom are members of the local Delta chapter, and soon we were at the boat ramp loading our gear and pushing off down the Atchafalaya. Minutes after we did, John Fogarty crooned wildly through the speakers, fresh air awakened our senses and civilization as we knew it waved adios in our wake.

Green Family Camp

The first thing I noticed when we arrived at the Green family duck camp was the sign. It was pure Old Testament: “Trespassers will be stripped, beaten, violated and abused…cooked alive, eaten and the remains thrown to the dogs.”

Thankfully, we were welcomed guests, and all that was asked of us was to help unload the gear and settle in for a night of good, clean fun before the morning’s hunt.

“What y’all think of the place?” asked Greg Green. “It’s not the Four Seasons, but it will do, don’t ya think?”

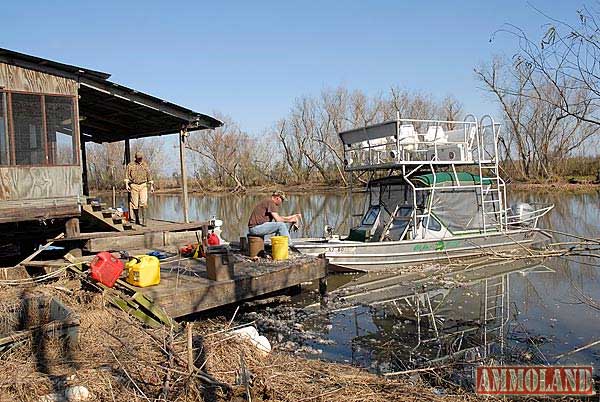

The duck camp itself is constantly becoming. Or, as Jeff Green says, “It’s constantly under construction.” Over the years, the camp has been torn asunder by hurricanes and other calamities, only to be rebuilt, augmented and rebuilt again.

The camp might not be the Four Seasons, but it’s not a tree fort on stilts, either. The kitchen has a gas range and oven, a sink, a long, rectangular-shaped island and a sturdy table and chairs. The living room has couches, lounge chairs and a big-screen television. Bedrooms and a bathroom sit down the back hall. In front, there’s a screened-in porch, and out back, a wooden deck complete with a grill and a nice view. A large generator makes the entire camp rattle and hum. Consider, too, the camp itself and its accoutrements were, at one time or another, boated in from Morgan City.

“This isn’t like going to hunt a rice lease,” Jeff Green said. “This camp has been in our family for 50 years, and ever since I can remember we’ve been putting into it as much as we’ve gotten out of it. I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

By early evening, all of us were sitting around the table, eating fresh oysters and a shrimp-and-oyster spread with crackers and leisurely drinking a few adult beverages, a ritual played out countless times over the years. Music, of course, was playing in the background. (The Green brothers have been known to bring in live music for special occasions at duck camp.)

The stories were plentiful too, thanks to Greg Green, the self-described director of entertainment. He wasn’t lying either. There are bona fide characters in this world, and then there’s Greg Green, who speaks so fast, and is so outrageously funny, you burn calories just listening — and laughing.

Thank goodness too. Before long, he had prepared a spread of deep-fried, hand-caught bullfrogs with spicy mustard, among other dipping sauces. They were lip-smacking sublime.

Albert Einstein once said, “Nothing will benefit human health and increase the chances for survival of life on Earth as much as the evolution to vegetarian diet.”

That’s perhaps debatable. But Einstein obviously never visited a duck camp in South Louisiana and ate Greg Green’s deep-fried frog legs.

“Cold frog legs are good fried food for breakfast,” Greg Green said, still in entertainment mode. “If you boys don’t lik’em, I’ll go out and get ya a nutria.”

“Go to bed little brother,” Jeff Green instructed. “You need your sleep.”

A heavy, roof-rattling rain began to fall, and an eerie fog rolled in as we went to bed. Wake up: 4:45 a.m.

“My worst-case scenario is waking up too early,” Greg Green said.

We all laughed.

Ducks For the Pot

The Green brothers rose before the alarm went off. Coffee was quickly on the boil, and before long, we were out the door and roaring down the bayou.

The plan was for us to break into two groups, with Greg Green, King and I hunting from a platform blind already brushed with natural vegetation.

The air was see-your-breath cool and the sky was mostly clear, with nary a hint of wind. The decoys sat listless as the morning sunrise — a spectacular ball of orange bracketed by a faint shade of crimson — inched above the horizon. The freshwater marsh finally came alive, although the birds were MIA.

“We need some wind,” King said.

“We need some ducks,” Greg Green said.

As the morning wore on, the wind picked up. Soon, the ducks started to move.

“You have a lot of gun-shy ducks this time of year, but it’s only a matter of time before we work a few in close,” said a smiling Greg Green as he cradled his trusty 10-gauge like a newborn. “But I don’t need ’em that close.”

True enough. A pair of wigeon came in from behind before swinging wide, roughly 45 yards from Greg Green. Two shots, two ducks.

“That’s two for the pot,” he said, laughing.

The action picked up quickly, with teal, gadwalls, shovelers, the occasional pintail and more wigeon vectoring in and around our spread.

“The thing about hunting these freshwater marshes in Louisiana is the number of species you see, day in and day out,” King said. “When you go hunt the flooded timber in Arkansas, your expectation is that you’re going to see and kill mallards. Not down here. It’s a gumbo of species, and I like that.”

During the 2010-2011 hunting season, Louisiana hunters filled their gumbo pots with 2.7 million ducks, the most of any state, and according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, more than all of Central Flyway states combined. That’s a per-hunter harvest of 30.6 ducks.

“We’ve had a good year,” Greg Green said. “The cold weather pushed a lot of birds down. You’ll get no complaints here. Who’d listen anyway?”

By noon, we had picked up our decoys and were headed back to camp with a nice mixed bag of puddle ducks.

“The gunning wasn’t heavy, but we did just fine,” Jeff Green said. “It was a good morning any way you cut it.”

Food, Family and Fun

We barely got off the boat and Jeff Green and McHugh were starting breakfast. The bacon sizzled in the pan and, of course, the eggs were eventually cooked in the drippings.

“Duck camp is about 75 percent cooking,” said Jeff Green, winking.

As we were eating, he fired up the grill with mesquite charcoal — he had a mess of doves he wanted to grill.

“I got a new concoction for you little brother,” Jeff Green said.

If bacon and eggs weren’t enough, he rolled out a long piece of tinfoil and placed the doves on it. He covered the birds with diced potato, onion, bell pepper and bacon, after which he splashed the dish with homemade wine and Coke, and liberally applied various spices. He formed the tinfoil into a tent and put it on the grill.

“Now we gotta give it some time,” Jeff Green said. “Time to clean some ducks.”

Beneath a peerless blue sky and the warming sun, in front of his family’s 50-year-old duck camp, Jeff Green plucked his ducks just like his Daddy used to.

“This place is about food, family and fun,” Jeff Green said. He has three daughters and a son. “I like bringing my kids out here.

It’s good for them. Kids who hunt and fish are less likely to deal and steal. It ain’t about killing, I’ll tell you that. It’s about spending time with family and friends. It’s about having a good time.”

“I’ve been hunting and fishing since I was a kid, and it’s just a way of living for us folks down here, and we’re proud of it,” added Greg Green. “I just don’t know no better.”

Tori McCormick is associate editor of Delta Waterfowl.

About:Delta Waterfowl provides knowledge, leaders and science-based solutions that efficiently conserve waterfowl and secure the future for waterfowl hunting. Visit: www.deltawaterfowl.org