Okay, here’s the scene. It’s England, September, 1754, and you’re the Duke of Cumberland, Captain General of the British Army. Word just arrived from the colonies that some young no-name from Virginia, a certain Major George Washington, had gotten his provincial butt kicked in western Pennsylvania by the French. And that makes you mad.

Not so much about Washington’s defeat at a place he called “Fort Necessity,” – he was just a grubby-nailed Colonial, after all – but because the French had had the temerity to venture that far south from their base along the St. Lawrence River and the eastern Great Lakes. That won’t do. To your thinking, the forests of western Pennsylvania are as British as grilled kidneys for breakfast, French claims and indigenous Native American nations not withstanding.

So what to do? Well, you’re leery of starting yet another major European conflict, (you’ll do so anyway—the Seven Years’ War), but you can’t let those French types skulking around in upper Ohio, erecting those Frenchy forts from which to taunt you. The answer? Send in General Edward Braddock – seasoned, commanding, unyielding (read: old, arrogant, incompetent).

As soon as Braddock set foot in Virginia in the spring of 1755, he got about the business of alienating practically everyone around him. To Braddock’s way of thinking, colonials were little more than escaped peasants and Native Americans no more than irredeemable savages. In short, Braddock packed an imperiousness—the ability to assume power without justification—excessive even by the standards of an imperial age. As the son of the governor of Massachusetts put it upon meeting the man, “we have a general most judiciously chosen for being disqualified for the service he is employed in almost every respect.” In 21st century speak, “This is the worst possible guy you Brits could have picked.”

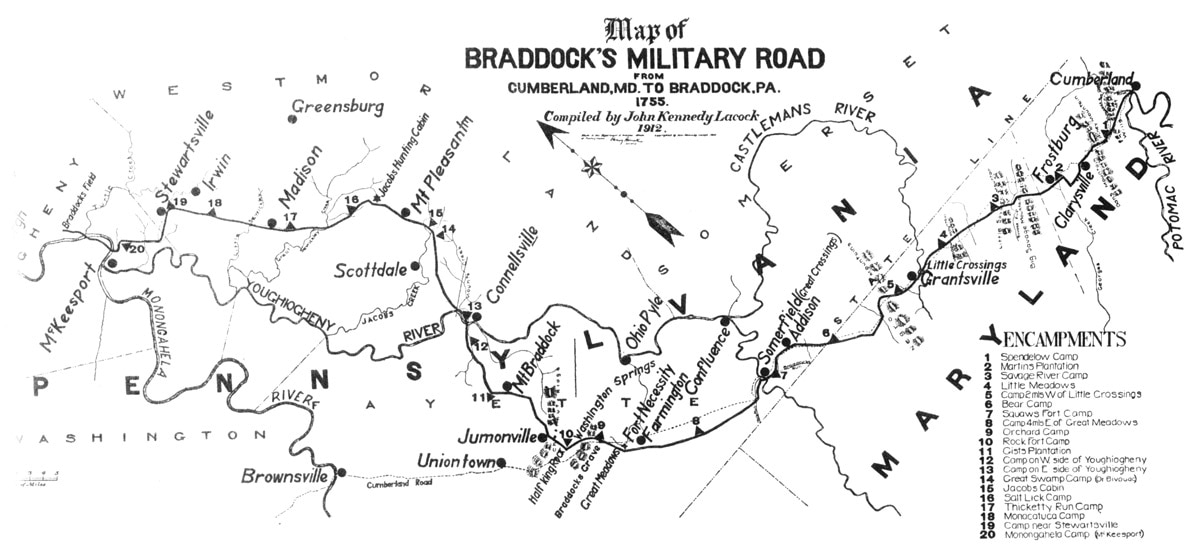

Braddock would quickly prove his detractor correct. Instead of moving lightly and attacking swiftly – wilderness-style fighting – Braddock brought his formal continental combat prejudices across the Atlantic with him and holed up at Fort Cumberland in western Maryland until he could be amply supplied with ponderous siege guns borrowed from Royal Navy ships. It was here that he also ran into serious logistical problems. In fact, were it not for Benjamin Franklin, who personally interceded with the farmers of Pennsylvania, Braddock might never have launched his offensive against Fort Duquesne, (the site of present day Pittsburgh).

When Braddock finally did get underway in mid-June, his army stretched out for miles in the forest like some kind of enormous, red-coated millipede. As the force of about 1,300 men neared the objective, George Washington, Braddock’s aide-de-camp, urged the general to allow the provincial troops, mostly Virginians, to scout ahead and patrol the surrounding hilltops to prevent ambush. Braddock, of course, would have none of it. Knowing that he outnumbered the French and discounting the French’s Indian allies out-of-hand, Braddock intended a classic, European-style siege, vanquishing the enemy’s fort with his superior artillery and that was all there bloody well was to it.

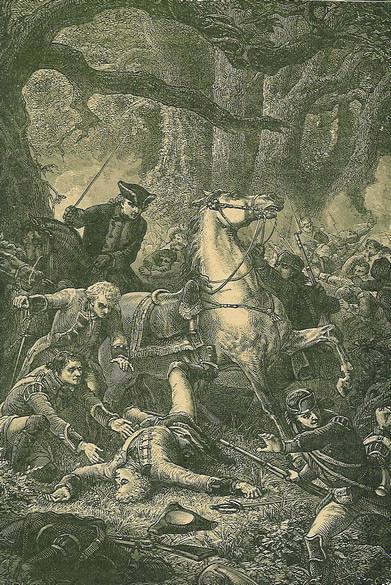

In the end, a child could not have set tin soldiers up more neatly than the marching ranks of British Redcoats who were ordered straight into the ambush as if they were on parade. Just over eight hundred French and Indians, occupying the high ground on either side of a ravine and sheltered behind trees – and wielding the French Tulle Musket of 1728 with its long, 46 ¾ inch barrel – massacred about 2/3 of Braddock’s force of 1,300 who fought with the famous Brown Bess, that ten-plus-pound of a musket that was almost as effective as a club as it was as a firearm.

In the end, a child could not have set tin soldiers up more neatly than the marching ranks of British Redcoats who were ordered straight into the ambush as if they were on parade. Just over eight hundred French and Indians, occupying the high ground on either side of a ravine and sheltered behind trees – and wielding the French Tulle Musket of 1728 with its long, 46 ¾ inch barrel – massacred about 2/3 of Braddock’s force of 1,300 who fought with the famous Brown Bess, that ten-plus-pound of a musket that was almost as effective as a club as it was as a firearm.

Not that they had much of a chance to club their attackers, however. Instead of having his Redcoats charge up one side of the ravine and fight their attackers hand-to-hand – a fight that the Redcoats with their superior numbers probably would have won – Braddock insisted that they maintain formation as though they were on the plains of Europe and not in the forests of Pennsylvania.

In the end, of course, a ball – almost certainly a .62 caliber from one of those Tulle muskets – finally found Braddock and he fell, mortally wounded. George Washington, miraculously escaped with “just” a couple of bullet rips through his uniform, lived to fight another day and many more to come.

The post Braddock’s Defeat, Brown Bess Rifles and the Tactics that Lost America appeared first on Guns.com.