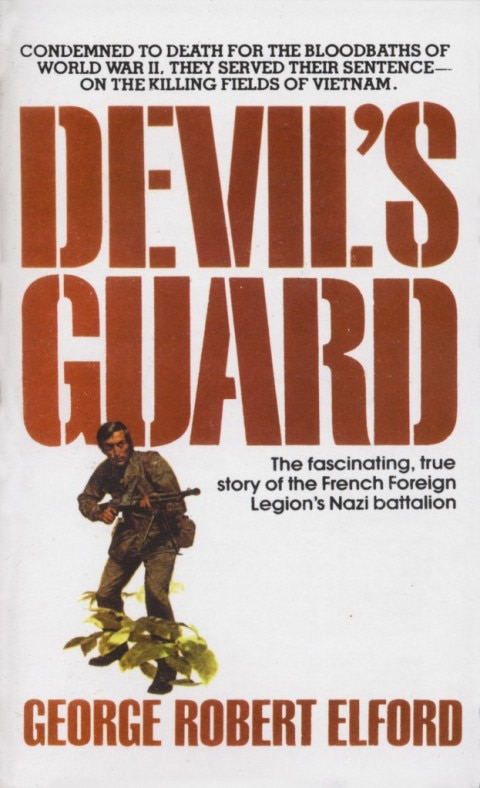

Though until recently unavailable for purchase, Devil’s Guard by George Elford is now back for less than $8 in paperback or digital download.

I don’t usually read historical war stories, unless I need a sleeping aid. Devil’s Guard by George Robert Elford did the opposite, keeping me up long past official lights-out to read what would happen next.

The book was recommended to me by a veteran who knows a thing or two about war and foreign security contracting. Since then I’ve come to learn it’s considered required reading for any serious operator. But even for those of us who don’t live and breathe war, it holds many lessons and opportunities for reflection.

Devil’s Guard is named such as it’s a firsthand account of an officer of the SS, Hitler’s elite security squad. As SS ranked above rank and file Nazi soldiers, their duties were, at times, especially high-risk and their actions especially heinous in the eyes of the enemy, or victims as most would say.

The story begins on Armistice Day, when the main character and his anti-guerilla unit are deployed outside of their native Germany. Their enemies remained militant following the war. The reader has a front-row seat to the theater of the troops’ nail-biting undercover trip back home, just to lay eyes on surviving family members before slipping away again to avoid detection in a world they once controlled, but in which they were suddenly wanted as criminals.

The unlikely protagonist and a handful of colleagues manage to go to the one place willing to welcome them—the French Foreign Legion camps of Cambodia, where a lower profile but no less violent war between Russian-backed communist guerillas, under Ho Chi Min, and some of the western world raged on. There, they form their own German detachments, applying their skills in secretive missions to small jungle communities near and sometimes inside enemy lines.

As the German detachment executes each mission, the reader is treated to rare insights into the expertise of a master warrior. From strategy to make the most of the terrain and supplies both official and naturally occurring, to combating the enemy with psychological tools, to the grittiest details of combat, there is no barrier of politeness between author and reader. Realities both poignant and grim are laid bare, free from fear of judgment in a style rarely seen in any form of writing.

By today’s standards, virtually no rules of engagement, save a code of moral decency that the core group agrees upon, encumber their exploits. On-the-move decisions are constant, and frequently involve whether individual civilians — sometimes women and children — are harboring enemy terrorists referred to as Viet Minh. The commander shares the temporary mental anguish of deciding whether to risk leaving possible communist sympathizers as they are, where they may grow in strength to fight based on knowledge of the French-German forces, whether to inconvenience or delay them to make a successful mission more likely, or whether to eliminate questionable characters on the spot.

In one such scene, a throng of 12 to 15 year old boys — typical targets of recruitment for suicide missions — are driven off a cliff, having been deemed not worth the waste of bullets. In another case, a group of once-esteemed, decent, decorated German soldiers are caught in the act of raping and murdering native women. The commander makes a pained but definite decision to exact severe punishment upon the men. In all such cases, the author wrangles with emotion prior to acting, but once a plan is put into action, it’s left resolutely in the past — a method surely easier in a deployment where death knocked at the door on a near-daily basis, requiring the troops’ full attention.

Hand-to-hand combat arises from both sides, generally with the Germans bearing bayonets, but in one especially gory encounter, rifle butts, boots, and fists end the lives of dozens of combatants on both sides. Discussion of weaponry is especially interesting. Although Elford doesn’t elaborate on types and calibers of rifles and the infrequently-appearing artillery, a frank discussion of the sharpshooter cadre fashioning silencers from bamboo is fascinating. The Viet Minh had little access to or knowledge of rifle sound suppression, but they were adept at their own silent death delivery — poisoned arrows. One harrowing account after another of Viet Minh ambushes with locally crafted tools leaves the reader with a healthy appreciation for their effectiveness.

The book is not without tender moments. In this very manly story, female characters do appear and some abide as allies. Some can shoot — very well. Elford shows equal skill for articulating the gentle effects of the feminine element in a savage world as well as he does the brutal aspects of war.

One element that should be of interest to anyone who watches the news is the contrast between the occasional headlines that reach the jungle operators in contrast to their experience. These warriors are no strangers to the use of propaganda and techniques for winning the minds of illiterate tribal citizens as compared to intellectuals. That experience is not wasted in Cambodia, and their genuine attempts to educate the populace help to win important native allies. Anyone who read To Kill a Mockingbird with interest will enjoy two accounts of courtroom-like presentations to natives, done in an attempt to help them recognize and inoculate their communities against communist control.

Long-range shooters, and those aspiring to be, will appreciate many tales of how scouting and mapping areas was critical to mission completion. Anyone who’s worked as a member of a multi-disciplinary team will nod in recognition of the team’s adroit management and use of talent.

Are some of the tales a bit exaggerated? Probably. It’s been said that the winner writes history, but this is one book in which the writer is the party kicked to the curb thanks to political moves far beyond their realm of influence.

Devils Guard gives a body the rare opportunity to peer into the mind of warriors-at-heart, grisly insights into the countless and horrid ways that human beings can torture and kill one another, and serves as a reminder of why it’s critical to fight the insatiable appetite of despots, wherever they spring up, for absolute control with no regard for human rights. It gives the western reader a veritable out-of-body experience to essentially ride along with the SS, one of the most vilified groups of recent generations, and get a glimpse into the hearts and minds behind the swastikas.

Is it true? No one is really sure, it seems. For sure, there are too many opportunities to wonder how the writer and most of his associates survived so many near-death ordeals. There is a voice swagger in some of the stories that smacks of fiction. Perhaps this is not one person’s account, but a collection of many war stories coalesced under the name of a single character. And one has to wonder how the war crimes trials the characters avoided shortly after World War II just disappear after their service to the Legion. Whether fiction, real, or something in between, it’s a riveting read.

This book was, for a while, unavailable for purchase. It’s back now, for less than eight bucks in either paperback or Kindle.

The post Book Review: Devil’s Guard by George Elford appeared first on Guns.com.