Tom says Ballistic Coefficient & Bullet Math is simple, keep reading to learn some shooting skills in our new long-range shooting science series.

USA –-(Ammoland.com)- Here’s why obscure [and some say boring] bullet ballistic concepts like ballistic coefficient and sectional density are essential if you want to hit targets regularly when shooting at long-ranges. Let’s assume you’re shooting a .308 rifle and you have two types of bullets of identical weight.

One is a 150-grain Sierra Pro-Hunter. It’s a lead-tipped, jacketed bullet with a flat-point tip and a flat base. It’s great for lever-action rifles and hunting.

The other is a 150-grain Sierra Matchking. It’s a jacketed bullet with a tiny hollow-point, non-expanding design. The base is a boat-tail shape. It’s great for accurate target shooting. Now, let’s launch them both at 2,750 feet per second from a Sierra Bullet Blaster 7000 rifle and see what happens.

After running the trajectory numbers based on atmospheric conditions here where I live in South Carolina, we get the following results.

| Sierra .308 150-grain FP | Sierra .308 150-grain Matchking | |

| Muzzle Velocity | 2,750 fps | 2,750 fps |

| Velocity, 100 yards | 2,379 fps | 2,510 fps |

| Velocity, 500 Yards | 1,334 fps | 1,649 fps |

| Velocity, 1,000 yards | 868 fps | 1,029 fps |

| Muzzle Energy | 2,543 ft-lbs | 2,534 ft-lbs |

| Energy, 100 yards | 1,885 ft-lbs | 2,098 ft-lbs |

| Energy, 500 yards | 592 ft-lbs | 906 ft-lbs |

| Energy, 1,000 yards | 251 ft-lbs | 352 ft-lbs |

| Bullet Drop, 100 yards | 0.00” | 0.00” |

| Bullet Drop, 500 yards | -79.30” | -63.24” |

| Bullet Drop, 1,000 yards | -678.10” | -475.78” |

| 10mph Crosswind, 100 yards | -1.50” | -0.93” |

| 10mph Crosswind, 500 yards | -44.69” | -28.36” |

| 10mph Crosswind, 1,000 yards | -206.53” | -142.47” |

These two bullets, while of the same weight, have different ballistic coefficients. The flat point Pro-Hunter has a ballistic coefficient of 0.185. The Matchking has a coefficient of 0.417. In the world of ballistic coefficients, a bigger number means that a bullet flies more efficiently.

OK, so with the Sierra flat point Pro-Hunter, I picked an unusual bullet to illustrate a long-range shooting ballistic concept, but that’s OK. As a shorter-range hunting bullet, it’s going to show the impacts of differences in ballistic coefficient more dramatically.

Rest assured, there will be performance differences between every two bullet designs of the same weight and different shape, just not as dramatic.

So why the significant differences even though bullets were of the same diameter, weight, and velocity? That boils down to more complex factors like shape, length, and weight distribution. Two measurements that help define the downrange performance of a bullet are ballistic coefficient and sectional density. As Sectional Density is a key input to Ballistic Coefficient, we’ll look at that first.

What is Sectional Density?

Sectional Density is a measurement that reflects the ratio of something’s mass to its cross-sectional area. That’s way too complicated, so let’s use an illustration.

Imagine launching a quarter at a target, but we somehow get it to fly face first, so the “top” flat side with George’s head is leading the way. We’ve got a big wide object pummeling its way through the air towards the target. From front to back along the flight path, the quarter is only 0.069 inches “long” when it’s flying face first because that’s the thickness of a quarter. A quarter flying this way makes a lousy bullet, right? So, in this case, the quarter has a very low sectional density because its mass is divided by a large number that represents its surface area.

Now imagine a nail flying point first. It’s long and narrow, so the surface area pointing into the wind is very small. The nail flying point forward has a very high sectional density because it’s long and skinny.

Simply put, sectional density is the ratio of weight to the diameter of the bullet. Technically, it’s the ratio of the weight to the surface area, but it’s easier to think in terms of diameter as that’s how bullets are measured. To grossly abuse math and physics, bullets with high sectional density are long and skinny. Bullets with low sectional density are short and fat.

Oh, and because our two example bullets above have the same weight and diameter, hence the same frontal surface area, the sectional density numbers are the same: .226.

What is Ballistic Coefficient?

Ballistic coefficient (BC) is a mathematical representation of how efficiently a bullet flies through the air. A bullet with a high ballistic coefficient is slippery and less subject to drag (slowing down) as it continues on its merry way. Here’s why.

Simply put, ballistic coefficient is a fudge factor. Back in the day, guys with lots of time on their hands fired boatloads of projectiles to figure out how they behaved in flight. The goal was to be able to predict how far projectiles would travel, the arc of flight, and at what velocity they would impact targets. Given that there is an infinite number of bullet types, weights, and shapes, doing all the math for each would be an impossible task. So, someone said, “Hey! Let’s design a ‘standard’ bullet and do all the math for that one. Then, for other bullet types, we can create a fudge factor that adjusts the standard bullet trajectory model.” That’s basically what the ballistic coefficient does. It adjusts the trajectory prediction for each bullet type.

As a fudge factor, the ballistic coefficient is usually a number between one and zero, but not always. Some big, heavy, and efficient bullets like the .50 BMG can have a ballistic coefficient greater than one, but that topic is for another day. The bottom line is this. The bigger the ballistic coefficient number, the more slippery the bullet, so it flies farther and faster than one with a lower coefficient. Remember that in our example, the Matchking had a coefficient of 0.417 while the Pro-Hunter had a BC of 0.185.

One more thing. You might see different BC numbers for bullets at different velocity ranges. That’s because the BC varies with speed. You don’t have to worry about that as your ballistic software will deal with it.

Drag Models

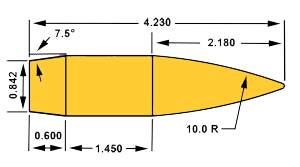

Originally, those smart people who did a lot of testing on the range worked out predictive models for bullet flight based on that “standard” projectile shape. If you look at the G1 bullet image, you’ll see that it resembles a common projectile shape from the 1800’s era, give or take. Since those early days, other smart folks have developed different predictive models on bullet flight based on a variety of bullet types.

Bullet Types:

- G1 (flat base with two caliber (blunt) nose ogive)

- G2 (Aberdeen J projectile)

- G5 (short 7.5° boat-tail, 6.19 calibers long tangent ogive)

- G6 (flat base, six calibers long secant ogive)

- G7 (long 7.5° boat-tail, ten calibers tangent ogive)

- G8 (flat base, ten calibers long secant ogive)

- GL (blunt lead nose)

These days, most bullet data is published with BC numbers for the traditional G1 drag model, but given the explosion of long-range shooting interest, more are also publishing numbers for the G7 model which is more accurate for sleek and slender long range bullets.

Here’s what you need to know about drag models. Ballistic calculators like smartphone apps and Kestrel devices take as inputs ballistic coefficients for a given drag model. That means that the BC numbers for a G1 and G7 drag model are different.

When entering this stuff into your Kestrel or ballistic smartphone app, be sure to use the right BC number with its corresponding drag model. As an example, the Hornady 6.5mm ELD Match bullet has a BC of 0.646 for the G1 drag model but a BC of 0.326 for the G7 drag model.

If your app or device asks for a G1 number, be sure to use 0.646. If it asks for a G7 number, use the 0.326 figure. Make sense?

The Bottom Line

All of this algebra and calculus mumbo jumbo is intended to solve one thing: to predict the behavior of a bullet as it flies through the air. The ability to know, in advance, how much a bullet will drop or drift in the wind at a certain distance allows you, the shooter, to make scope holdover adjustments that will increase the odds of you hitting your target. It’s that simple.

About Tom McHale

Tom McHale is the author of the Practical Guides book series that guides new and experienced shooters alike in a fun, approachable, and practical way. His books are available in print and eBook format on Amazon. You can also find him on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and Pinterest.