The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives released a report back in June that details an account of firearms that were reported lost or stolen in 2012. The report, which will be updated annually, was part of 23 executive actions set forth by President Obama in January in an effort to reduce gun violence in America.

While any lost or stolen firearm is cause for concern, the numbers indicated in the report show that the unaccounted for firearms pose a serious threat to both public safety and law enforcement. The main reasons being, “Those that steal firearms commit violent crimes with stolen guns, transfer stolen firearms to others who commit crimes, and create an unregulated secondary market for firearms, including a market for those who are prohibited by law from possessing a gun,” the report states.

The study reflects a total of 190,342 lost or stolen firearms nationwide from both private individuals and Federal Firearms Licensees. Nearly 17,000 of those firearms, or about 9 percent, were reported lost or stolen from FFLs. Additionally, of those, more than half were reported lost, with less than 6,000 reported stolen from FFLs.

And while this may seem like an alarmingly high number, it’s important to note that firearm thefts, just as all other types of theft across the country, have actually been on a steady decline in recent years.

The report looked at data available from all 50 states, as well as the District of Columbia, but also included information from Guam, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands.

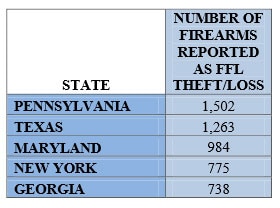

Texas was the state with the most reported lost or stolen firearms, followed by Georgia, Florida, California and North Carolina. Pennsylvania topped the list for the most reported lost or stolen firearms from FFLs, with Texas, Maryland, New York and Georgia close behind.

The states with the fewest number of reports – outside of Guam, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands – were Hawaii, Rhode Island, North Dakota, Vermont and South Dakota, with all reporting less than 315 lost or stolen firearms for the entire year. Of the reports filed by FFLs, Hawaii and D.C. are tied for number one with not a single report, followed by New Jersey and North Dakota. New Hampshire and South Dakota are tied for fourth place, while Delaware is fifth with 30 reports.

Although the report did not reveal information surrounding the specific types of firearms reported as lost or stolen from private individuals, it did provide a breakdown of this data concerning reports from FFLs. The overwhelming majority of lost or stolen firearms were pistols, with more than half of those the result of theft from burglary, larceny or robbery. However, rifles were the main type of firearm which were reported lost, with nearly 1,000 more reported than the stolen pistols.

Although the report reveals some interesting and useful data, the information is also flawed or misrepresented in several ways, as pointed out in the study, and that should be considered when reviewing the report in its entirety.

A snapshot of the states with the highest number of reported FFLs with lost or stolen firearms. (Photo credit: ATF)

While the ATF reported just over 190,000 missing or stolen firearms last year, the number – particularly for those lost or stolen from private individuals – is likely an inaccurate count. Federal law requires that FFLs file a report within 48 hours of discovering a missing or stolen firearm. However, in most states, no such laws exist for private citizens and reporting these firearms lost or stolen is strictly voluntary, not mandatory. In fact, only 10 states — Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Jersey, New York, Ohio and Rhode Island – and D.C. have such a requirement. And in the state of New Jersey individuals are held with civil liability for stolen firearms.

Additionally, the study warns, “This is raw data that has not been substantively reviewed by the FBI, has not been screened for duplicates or other data entry issues, and does not account for firearms that were subsequently found or recovered.”

In other words, while the number of actual firearms that were lost or stolen may actually be higher than what is represented due to underreporting, the number may also be lower due to duplicate entries or other errors and recovered firearms not subsequently being removed from the list.

The matter is further complicated by often missing serial numbers. Private citizens many times do not have the serial numbers available to give to authorities when they report a firearm lost or stolen. For all practical purposes, those guns then become lost in the system because even if they are recovered, without those numbers there is usually no definitive way to identify them.

Additionally, when firearms are stolen the serial numbers are usually altered or removed in some way, as to eliminate that identifying factor. Again, if those firearms are later recovered, there’s no way to technically determine that they were stolen to begin with.

Another complicating factor is the very means by which some FFLs discover lost firearms. According to the report, “The fact that an FFL reports a firearm lost in a specific calendar year, however, does not necessarily mean that the firearm was physically lost in that calendar year.” Sometimes when an inventory inspection occurs, either by the ATF or independently, firearms which were accounted for in previous years, are no longer found in the inventory. “Although some of these firearms may have been transferred to lawful purchasers, they are reported as lost because the FFL has not accounted for the disposition of the firearm in their business records,” the report explains. Concluding, “In these instances, the year of actual loss may not be known and is reported in the year that the inventory was conducted.”

Yet as pointed out by the National Shooting Sports Foundation, FFLs have much greater legal and economic incentives to not only maintain adequate records, but safeguard against loss and theft than most private individuals.

The legal incentives come from the legitimacies of possessing an FFL and the possible repercussions of not keeping pristine records and ensuring all that can be done to reduce loss and theft is done.

The economic incentives obviously arise from the fact that a firearm that is either lost or stolen cannot be resold by the FFL for profit. So each lost or stolen firearm equates to several hundred or even several thousand dollars in loss for the business.

However, the NSSF encourages regular inventory inspections and endorses products designed to secure against theft through their “Taking Stock” initiative. In addition, the NSSF also matches any reward offered by the ATF in relation to the theft of firearms from a licensed firearms retailer.

The NSSF believes that these voluntary measures have effectively helped to keep firearm loss and theft among FFLs at a very low level. In fact, the firearms reported lost or stolen from FFLs only account for about 0.15 percent of all of the guns either made or imported into the U.S.

The post ATF reports over 190,000 firearms lost or stolen in 2012 appeared first on Guns.com.