Argentina Dove Hunting – Do you Have What It Takes

Presented by Cheyenne Ridge Signature Lodge

Columbia, SC –-(Ammoland.com)- by Roger Pinckney: Down at the Plaza de Mayo, the Argentines are beating each other with sticks.

The Peronists have stormed their own headquarters and will not come out until they call a bomb threat on themselves.

We are a couple of miles away at El Aeroparque Jorge Newberry, and the pilots are on strike.

Argentine pilots have not been paid in two weeks, but we are flying LAN Chile. There is no great love lost between the nations. Argentines tell you they are the steak and Chile is the bone for the dogs. If I told you what the Chileans say about Argentines, they would not print it here. So LAN will keep flying, but late. Instead of shooting birds in Cordoba, we are wishing it wasn’t too early for Senor Jack Daniels.

Me and Claudette, my second trip, her third. Two hours later there is a stirring at the gate, an Airbus making ready to load. No jetway here, downstairs, across the tarmac and up a ladder. The guncase goes up the conveyor and thumps into the cargo bay.

Bringing your guns to Argentina? Not for the harried, hurried or the faint of heart. You send your outfitter the numbers six weeks in advance and he generates the papers on his end. Somebody meets you at the gate and escorts you to an office where special police check serial numbers and collect a hundred bucks a gun, more if they feel like it. A deal if you figure it by the page, the artistic flaring fancy wristwork in stamp, stamp, stamping each individual sheet half a dozen times. Argentines, weary of coups and threats of coups, keep a close eye on guns coming into the country.

We have a side-by-side and an over-under, two high-grade Merkel 20s. Merkel was among the German gunmakers who wound up on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain. The Reds consolidated all the companies into one grand firearms collective to make shotguns for high-rolling Comrade Commissars. When the wall came down, Merkel reorganized and moved into the western market. And that’s where we come in. We’re taking Merkels to a land where Benellis and Berettas rule. We will see how they hold up.

But we have to get there first. A bus from the estancia meets us at the Cordoba airport. We are late, but earlier than the sole Argentine flight, which delivers a contingent of Texans.

“What yall got in the box?” one wants to know.

“Merkels,” I say.

“Myrtles?”

This country looks like eastern Montana, broad flat fields, checker-boarded by fence-rows and hedgerows with a line of ragged blue hills in the distance, but the cowboys hanging around the crossroad cantinas wear berets, not Stetsons.

One town short, there is a barricade of tires, pallets and sections of drag-harrow, teeth up. Dour campesinos are standing around with sticks.

“Do not worry, senores,” the driver says, “it is only the farm protest.”

The campesinos thrust leaflets through the windows, wave us on.

We arrive at Estancia Los Chanares in time for lunch. Lunch is a serious undertaking in Argentina and will burn up about two hours. Fresh bread, an extravagance of salad, potatoes, steaks, ribs, dove breasts, wine, wine, wine and finally homemade ice cream and fruit cobbler. We waddle from the table and get introduced around.

Alex, a Columbian and lifelong hunting guide, runs the lodge. His wife, Jessica, a veteran restauranteur from Buenos Aries, runs the kitchen. Martin organizes the shoots, ramrods the bird boys and fixes the guns when they need fixing, which is more often than you might expect.

Most estancias offer shooting wintertimes to help spread out the pesos – and to thin flocks that can easily flatten a grainfield in an afternoon. But Estancia los Chanares manages crops for the birds, instead. The lodge is grand enough for any exiled ex-presidente, white stucco, fireplaces everywhere, formal gardens, swimming pool, red tile roof and red tile floors. The fields are angular and irregular, troublesome for agriculture but perfect for food plots. All around are rotten stone hills of impenetrable thornbushes – chanares – hence the name of this distant, obscure and excellent place.

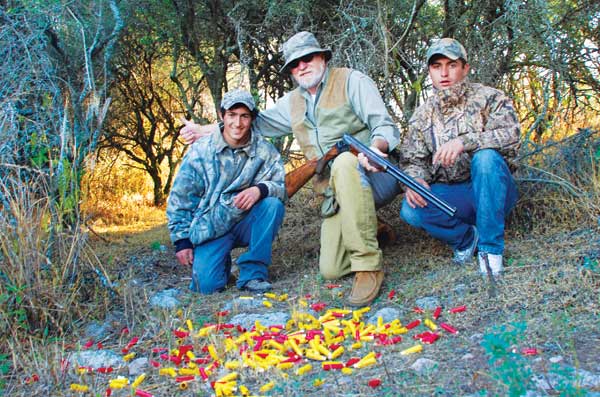

We meet our bird boys at the first stop, Hugo and Juan, brothers in their early 20s, swarthy, beady-eyed and diligent. Two cases of shells, two field-seats, two coolers of water and Quilmes, the favored local brew, feed sacks for the birds and the empty shells.

They lead us to a makeshift blind strung between two thorn trees. They break out the shells – Orbeas made right up the road in Tucuman – and we break out the guns. Hugo and Juan tip boxes and the shells rattle into our vest pockets.

I learn a lot that day. You can only shoot one bird at a time. A ventilated rib is a radiator. Your gun will cool faster open and propped vertically against a convenient tree. Finally, don’t forget your shooting gloves. Splat – blood across my glasses. The new checkering has worn the hide right off my thumb.

“You boys got any band aids?”

“No, senor, but Martin will have them when he brings more shells.”

“More shells?”

“Si, senor, these two cases will not last you so long.”

Winter daylight comes late in these latitudes. Reveille at eight, a bounteous breakfast at 8:30. Alex and I linger over coffee.

“How many birds do you have?”

He smiles. “Twenty millions? Forty millions? Who knows? We have the largest dove roost in all of Argentina.”

We ride to the morning shoot with a new arrival, Harvey Alexander from London. He’s ecstatic.

“I can fly first class from London to Buenos Aires and shoot here for less than it costs me to shoot driven grouse in England!”

We find Hugo and Juan on a foot-trail atop the brow of a long hogback ridge. There is a brightening field on one side, thornbush tangle on the other. After the pickup rattles away we notice a sound persistent as distant surf, as if the earth itself is breathing. Millions upon countless millions of doves are cooing up the morning. Already the air is full of them and the green hills echo with the crackle of gunfire.

But how many doves can a man shoot? How many birds does a man want to shoot? Last year another Texan tried to figure it out. He shot 6,016 doves in 11 hours using three extended magazine Benellis. He kept three bird boys busy, two loading, one counting. Not sure of his shell bill, his hospital bill either.

A couple of hours into it, Claudette cusses. A fine screw in the forend hardware has worked itself loose.

“Y’all got a screwdriver?”

“No, senor, Martin will bring when he brings more shells.”

I sit crosslegged in tall grass and pull the forearm off the gun. The screw retains a cam that cocks the top barrel ejector.

“If we can’t get us a screwdriver, we won’t need more shells.”

“No problemo, senor,” Hugo says and pulls a battered jack knife from his jeans.

I baby the screw with a thumbnail instead. My nail splits, but the gun will shoot.

We break for lunch, I peel the forend again and pass it to Martin. He returns it with ceremonial flourish right at the table, along with an eyeglass screwdriver, custom ground to fit the fine Merkel screw. Back in business, for awhile anyway.

A couple dozen boxes into the afternoon shoot, the double bellers and slaps my already pulverized shoulder twice as hard as expected. I reckon somebody in Tucuman got careless with his powder dipper. Juan comes to my side, looks over my battered shoulder as I puzzle over the gun.

“It has fired twice, senor.”

He’s right. “Martin!”

On our way out of the fields, we pick up one of the Texans holding what’s left of a semi-auto. The receiver literally fell apart in his hands.

“I was hoping to shoot a thousand birds today,” he bemoans, “but damnit, all I got was seven-fifty.”

Nothing serious. An aluminum receiver with egged-out holes. The pins that secure the trigger group fell into the thorn tree leaves. Martin has a zip-lock of them back at the estancia.

I quiz Martin. “How many rounds been through that gun?”

He shrugs. “In two years, maybe fifty thousand.”

“Fifty thousand? How do your over-unders stand up?”

“They break hammers around sixty thousand. I can adjust them, but then they break springs.”

“What’s the absolutely toughest gun?”

“The Browning Citori, senor. But the firing pins erode . . .”

Clang, clang, bang. A wind is roaring down the Andes and every rattly piece of metal, every gate, every loose board for a hundred miles is picking up the lunatic rhythm. Clang, clang, clang. I ease out of bed and pad down to the great room looking for coffee. Harvey Alexander, the wandering Britt, is hooked over a Cuban cigar and his cell phone. The cigar works, the phone doesn’t.

I leave my doubling Merkel on the gunrack and hornswoggle Martin out of one of the house guns, a Beretta Silver Pigeon 28. It’s only a year old, the checkering has worn right off the stock, but it functions flawlessly. And Brothers and Sisters, I am here to testify that you can kill the hell out of doves with a 28. I drop the first 16 straight. I tell you this not to brag, but only so you can share my astonishment. Forty yards, sixty yards, doesn’t matter. Deadly beyond belief.

Claudette is shooting the Merkel over-under and besides having to keep after the troublesome screw, she is dropping birds left and right. But the wind is still ripping. We are shooting from a hole hacked out of the thornbushes halfway down a steep ridge. Birds careening downwind are just an impossible blur. Upwind it’s a little better. Upwind or down, the birds can’t see us until they are right on top of us. But we can’t see them either and have only about two seconds to mount, swing and fire.

Maybe you never reckoned wingshooting an endurance sport, but here in Argentina it is. Three days and it shows.

Poor us, too tired to shoot anymore. We let the guns cool down one last time, crack a Quilmes. Back at the estancia, they have a fire roaring in the outside pit and the liquor is going down.

“The girls are coming out from Cordoba,” Alex announces.

“Who wants a massage?”

Eighteen hands in the air.

The bus is idling in the driveway. We powwow with Alex and settle our shell bill, painful at ten bucks a box. That’s the way they do it down here, turn you loose in a blizzard of birds and keep careful count. Between the two of us, we have downed a thousand birds, an affront, an insult, a mockery. But Alex acknowledges our sensibilities.

“We have a couple from Sweden who come every year. They enjoy themselves but will only shoot five hundred birds each,” he pauses, then adds, “a day.”

Halfway to the airport, there is a monumental jam of trucks and cars and buses. The campesinos are still at it. Our driver hooks a hard right and takes us cross-country. After three or four miles eating dust, we are clear of the campesinos and on the main road again.

Back at our Buenos Aires hotel we are met by a harried bell captain who passes us a printed notice:

“There are some issues of local concern that have prompted rallies at the Plaza de Mayo . . . ”

We wake next morning to a rumble as pervasive as ten million doves cooing, heady as a wind coming off the Andes. Fifty thousand campesinos have bolted the pampas and are heading to the Plaza de Mayo. Busloads after countless busloads. Musicians on the back of flatbed field trucks. Funky little Fiat sedans with blaring loudspeakers big as the cars. Meanwhile, the government has laid off their legions of clerks, paid them 200 pesos each to go protest the protesters.

Claudette considers the proceedings and then glances at the clock.

“We have a couple of hours to kill. Let’s slip off to some sidewalk cafe and get us one good last meal before things bust loose.”

Just a snack, a dozen poached shrimp on a bed of lettuce, tomatoes and avocadoes, home-baked bread and the obligatory local wine. Then a series of low concussive thumps comes rolling over the rooftops.

“Hey waiter, what’s all the racket?”

He wrings his hands, mops his brow and looks uneasily off into middle distance.

“Please do not worry, senor. It is only the tear gas bombs.”

Ah Argentina, I have what it takes to love you, a little money, a little Spanish, a little patience, and a great sense of humor . . .

Editor’s Note: Roger Pinckney happily reports a drop of lock-tight fixed the over-under and there was nothing at all wrong with the side-by-side. His hand was so swollen, it crowded the selector button to middle position allowing both barrels to fire simultaneously.

About:

Sporting Classics is the magazine for discovering the best in hunting and fishing worldwide. Every page is carefully crafted, through word and picture, to transport you on an unforgettable journey into the great outdoors.

Travel to the best hunting and fishing destinations. Relive the finest outdoor stories from yesteryear. Discover classic firearms and fishing tackle by the most renowned craftsmen. Gain valuable knowledge from columns written by top experts in their fields: gundogs, shotguns, fly fishing, rifles, art and more.

From great fiction to modern-day adventures, every article is complemented by exciting photography and masterful paintings. This isn’t just another “how to” outdoor magazine. Come. Join us! Visit: www.sportingclassics.com